Digging into HermeticWiper

By Max Kersten · March 2, 2022

A special thanks to Marc Elias for his help during my analysis. Additionally, I’d like to commend all researchers who have publicly shared their initial findings to help incident response teams; I hope this deep dive contributes to a further understanding of the malware’s inner workings.

On the 23rd of February 2022, the HermeticWiper malware was first observed in Ukraine. The malware aims to destroy the boot sectors of any (removable) disk on the infected machine, with the help of a benign partition manager driver. This blog is split up in three main sections: a deep technical dive into the HermeticWiper sample’s inner workings, a comparison with the recent WhisperGate wiper, and a brief word about attribution.

Technical analysis

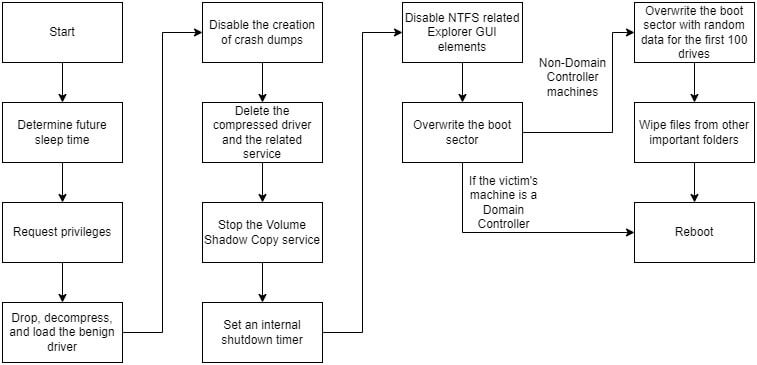

The complete technical analysis is summarised in the flowchart below. Each aspect will be explained in detail, with accompanying segments of code to further clarify the malware’s inner workings.

The analysed sample’s hashes can be found in the table below.

| SHA-1 | 61b25d11392172e587d8da3045812a66c3385451 |

| SHA-256 | 1bc44eef75779e3ca1eefb8ff5a64807dbc942b1e4a2672d77b9f6928d292591 |

| MD-5 | 3f4a16b29f2f0532b7ce3e7656799125 |

Benign software and certificates

Even though there are multiple stages, the malware starts out as a single signed executable. The certificate which was used to sign the malware originates from Hermetica Digital Ltd, a Cyprus based company who seems to be another victim in this ordeal, as the company’s owner denies any involvement, per Reuters. The usage of certificates in malware is not new, and solely serves to mask the file’s malicious intent.

Start-up checks and privileges

The first check within the wiper, is the verification of the number of command-line arguments. Later on, a sleep is called for a given number of seconds. If a valid integer is provided as a command-line argument, that value is used. Otherwise, a hardcoded value is used.

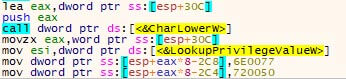

To avoid execution in an analysis environment, the malware verifies if its name starts with a “c”. When downloading malware from sample sharing sites, the file name is often equal to the hash of the file using a common algorithm, such as MD-5, SHA-1, or SHA-256. The (lack of) capitalisation of the character is irrelevant, as the call to CharLowerW ensures the comparison is made using a lower-case “c”, as can be seen in the screenshot below.

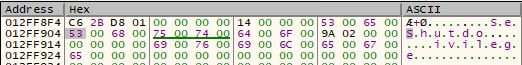

The numeric value of this character, stored in EAX, is used to calculate the offset on the stack to place the missing wide characters to complete the “SeShutdownPrivilege” wide string. The two mov-instructions in the image place the missing wide characters at the calculated offset. The image below shows the original wide string.

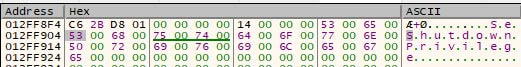

Note how “wnPr” are missing in the middle of the wide string. Once the four wide characters are inserted, the string is completed, as can be seen below.

Up next is the check for both the above-mentioned privilege, as well as “SeBackupPrivilege”. The two privileges are then requested using AdjustTokenPrivileges. Regardless of the request’s success, the malware’s execution continues. The difference the privileges make will be clear later on.

Loading the benign driver

The malware then calls a function to drop and load the afore-mentioned benign driver, originally created by EaseUS for its partition manager, and signed by CHENGDU YIWO Tech Development Co. Ltd., the creator of said software. Note that the driver is benign and misused by the malware.

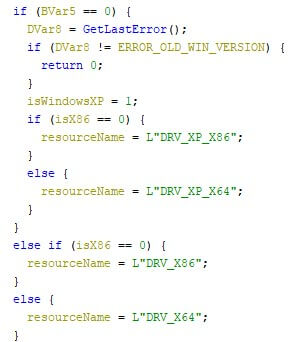

The driver is embedded (compressed using the MSLZ format) into the wiper’s resources, where it contains four versions, pending on the victim’s operating system and CPU bit-ness. The driver versions are for Windows XP, both 32-bits and 64-bits, and for any later Windows version, also in both 32-bit and 64-bit. The image below shows the corresponding code.

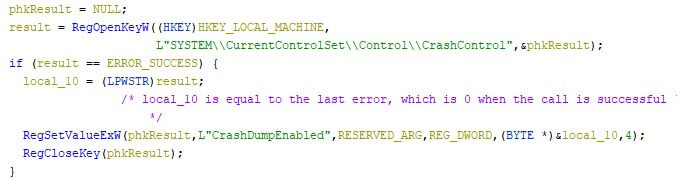

The wiper first checks the Windows version, which is later used to load the corresponding compressed driver from its resources. The malware then disables the creation of memory dumps when the system crashes. It does this by setting the registry key at “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\CrashControl\CrashDumpEnabled” to 0, as can be screen in the screenshot below.

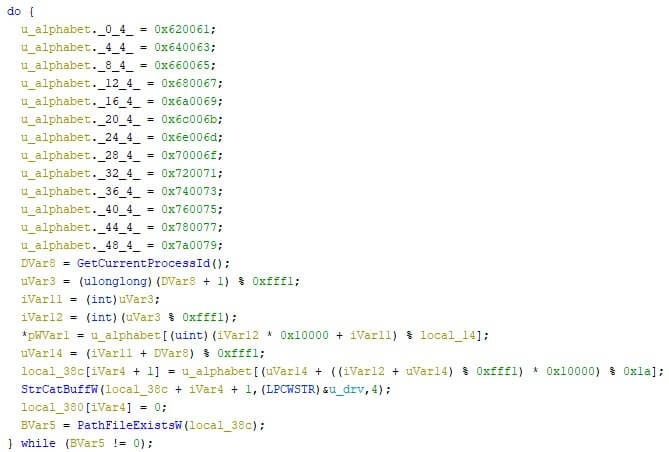

The respective compressed driver is then loaded from the resources, and written to “C:\WINDOWS\system32\drivers\[XX]dr”, where “[XX]” are two randomly generated lower case characters from the Latin alphabet, ranging “a” through “z”, as can be seen in the image below.

The compressed file is then read from the disk, decompressed, and written to disk using the same file name, with “.sys” added to it.

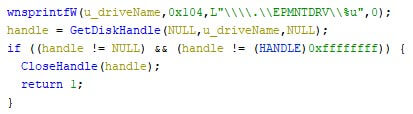

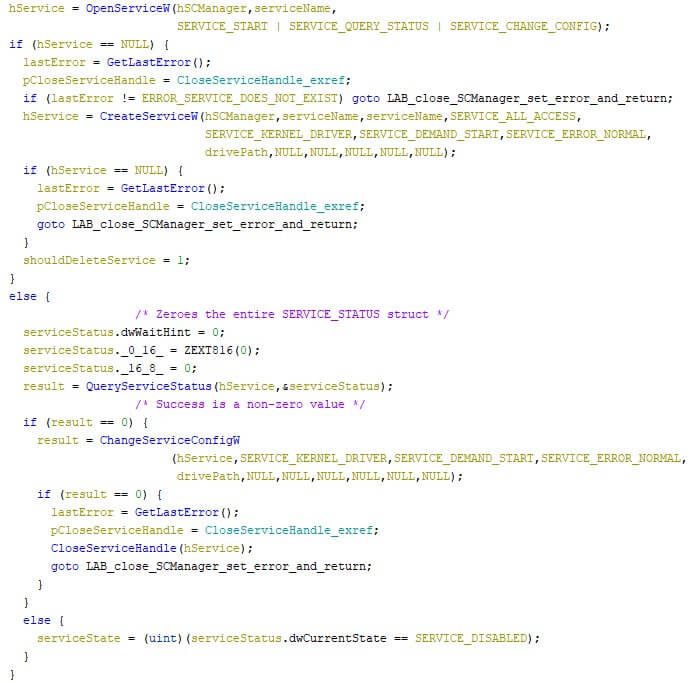

Next, the wiper attempts to acquires the “SeLoadDriverPrivilege” privilege. If this permission is not granted, the malware terminates itself. An attempt is then made to get a handle to the benign driver, which is accessible via “\\.\EPMNTDRV\” with a given unsigned integer. If this is possible, there is no need to repeat the driver loading procedure. The snippet below shows the relevant code.

If the driver cannot be accessed, meaning the above failed, it is then loaded. If the service state is disabled, the wiper will check up to four times if the service is running, with a one second sleep in-between to allow the service to start. The image below shows the corresponding code.

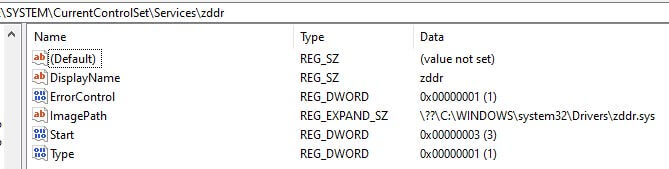

Upon the successful creation of the service, the compressed driver is removed from the disk, together with the service’s corresponding registry key, and its values. The screenshot below shows the service’s values in the registry. Note that the service’s name, which is equal to the driver’s name, is “zddr” in the analysis.

Disabling Windows internals

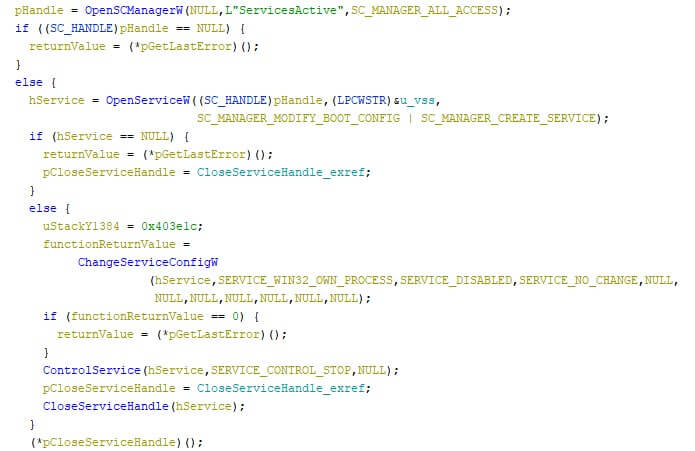

Following up on that, the Volume Shadow Copy service (abbreviated as “vss”) is stopped. This service creates incremental back-ups over time, and is often disabled by ransomware for the same reason as the wiper disables it: discontinuing the internal back-up system of Windows. The relevant code can be found in the excerpt below.

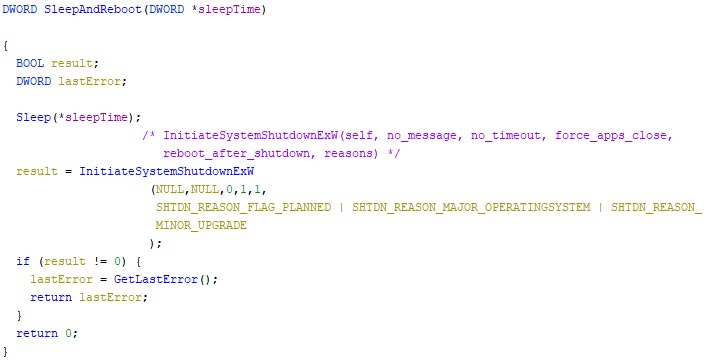

The wiper then recursively overwrites files located at “C:\System Volume Information”, after which attempts to forcefully and instantly shut the system down via a thread, which first sleeps for a given number of seconds. Note that the “SeShutdownPrivilege” is required to call the shutdown function. This privilege is only obtained if the first character of the malware’s file name is a “c”, regardless of the casing, as explained in the start of the technical analysis. The screenshot below shows the corresponding code.

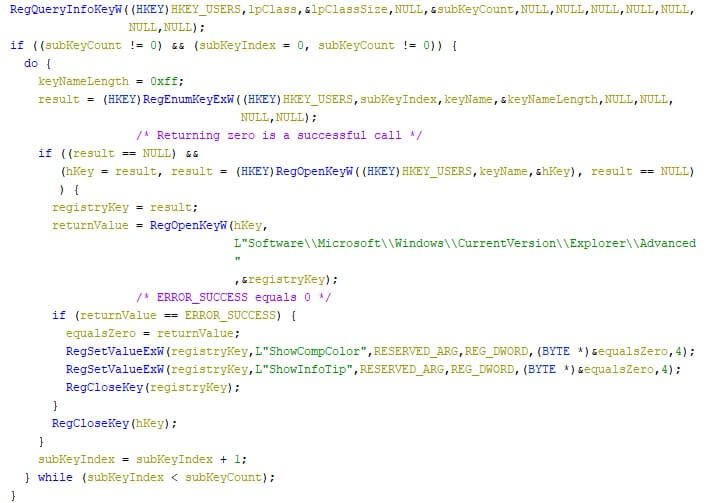

Further changes to the registry are then made, where “ShowCompColor” and “ShowInfoTip” (both located at “HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\Advanced”) are set to zero, for each user. These registry keys define if compressed NTFS files should be displayed in colour, and if tooltips should be shown for folder and desktop items, respectively. The screenshot below shows the corresponding code.

Wiping data

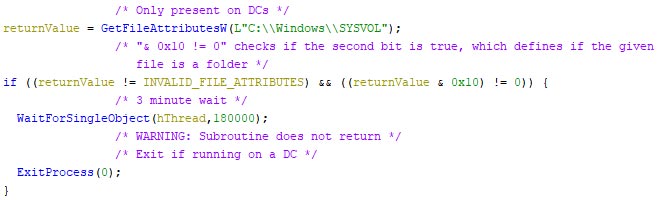

The malware then checks if the machine where it is executing on, is a Domain Controller. The folder “C:\Windows\SYSVOL”, which only exists on Domain Controllers and contains the policies, is checked for its existence, and if it is a folder. The excerpt below shows the check.

If this is true, a three-minute wait is entered, allowing the threaded overwriting of the boot sectors of any attached removable or fixed medium, as can be seen in the image below.

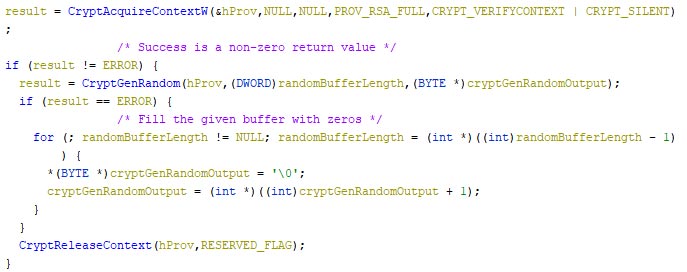

The data which is used to overwrite the boot sector is random data, which is generated via Windows Cryptography API calls, unless an error occurs. If an error occurs, the data is overwritten with zeroes. The image below contains an excerpt of the random data generation function.

Once the three-minute wait is over, the malware shuts itself down. As such, further details within the technical analysis section are only for machines that are not a Domain Controller.

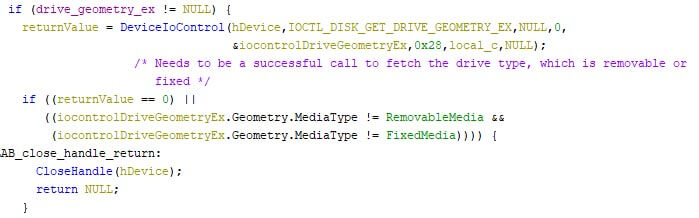

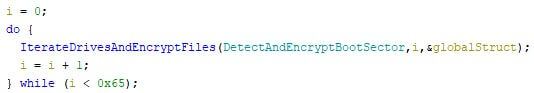

The wiper then iterates over the first 100 attached drives, and overwrites the boot sector of each attached removable or fixed medium.

The malware then recursively overwrites specific files in “C:\Documents and Settings” and “C:\Windows\System32\winevt\Logs”. The goal here is to wipe data and minimise the amount of usable forensic artifacts.

Yet another wiper?

There is more to these two campaigns than their shared destructive nature. Needless to say, wipers have been used in various forms, and they are here to stay. Some infamous examples are, in no apparent order: WannaCry, NotPetya, Shamoon, and WhisperGate. Note that even though some of the mentioned samples are classified as ransomware, but the way they were used made them wipers instead.

The WhisperGate campaign targeted the boot record of the affected device, much like the Hermetic wiper does, albeit less thorough. The Hermetic wiper goes over the first hundred physical drives and ruins the boot record if it fits the predefined criteria, as mentioned above.

Additionally, the usage of a legitimate driver to wipe data differs wildly from the WhisperGate campaign. Whether the driver is used as an attempt to fly under the radar of security products or simply a preference of the wiper’s creator, it’s an effective way to achieve the actor’s goals.

A major difference between the two, is the quality of the code. Whereas WhisperGate’s boot record replacement was shoddy at best, the Hermetic wiper’s code base shows an in-depth understanding of volume formats and their handling. Even though there’s a noticeable difference in code quality, it is clear that both campaigns have had a disastrous effect on all systems they were executed on.

Victimology and Attribution

The majority of the reported victims (both publicly and in our telemetry) are located in Ukraine, dating back to the 23rd of February 2022. Some victims have also been observed in other countries, but due to the limited amount, those are likely foreign office for Ukrainian companies.

Per our telemetry, there is an overlap of Ukrainian victims who were victim in both WhisperGate and this campaign. The sectors of the victims seem to align with the military strategic goals of an aggressor: disruption in the communication of an opponent in war time.

Given the fact that the sample’s code is newly created, there is no overlap with other samples that have been found in other malware families. One can argue that the malware campaign’s timing, just before Russia’s invasion into Ukraine, is more than a coincidence. Based on the destructive nature of the malware campaign, while also taking the campaign’s timing into account, we attribute this campaign with medium confidence to a pro-Russian actor.

Conclusion

Wiper campaigns have been used in the past and have proven to be effective. The usage of benign software for a malicious purpose, often referred to as dual-use, is common and widely adopted. Dual-use software can be found in the form of living-of-the-land binaries, or self-contained benign files. The HermeticWiper does the latter with the embedded driver, as the boot sector altering actions are performed by a benign driver, in-line with the expected behaviour of said program.

It comes as no surprise that the digital domain is actively used during war times, given the ever-increasing digitalisation of the world around us, as the pandemic has clearly shown. The pro-Russian targeting of the victims, along with the timing, shows the direct impact the digital domain has in our lives.

RECENT NEWS

-

Jun 17, 2025

Trellix Accelerates Organizational Cyber Resilience with Deepened AWS Integrations

-

Jun 10, 2025

Trellix Finds Threat Intelligence Gap Calls for Proactive Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation

-

May 12, 2025

CRN Recognizes Trellix Partner Program with 2025 Women of the Channel List

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Details Surge in Cyber Activity Targeting United States, Telecom

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Advances Intelligent Data Security to Combat Insider Threats and Enable Compliance

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.