Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

Evolution of BazarCall Social Engineering Tactics

By Daksh Kapur · October 6, 2022

What is BazarCall?

As nicely defined in this article by Microsoft:

BazarCall campaigns forgo malicious links or attachments in email messages in favor of phone numbers that recipients are misled into calling. It’s a technique reminiscent of vishing and tech support scams where potential victims are being cold called by the attacker, except in BazarCall’s case, targeted users must dial the number. And when they do, the users are connected with actual humans on the other end of the line, who then provide step-by-step instructions for installing malware into their devices.

BazarCall campaigns first came into the limelight in late 2020 and since then Trellix has seen a constant increase in attacks pertaining to this campaign. It was initially found to be delivering BazaarLoader (backdoor) which was used as an entry point to deliver ransomware. For those interested in more details about BazaarLoader, this article by “The DFIR Report” contains a comprehensive explanation on how a BazaarLoader infection led to the installation of Conti Ransomware in a span of 32 hours. As the BazarCall campaign grew, it was also found to be delivering other malware such as Trickbot, Gozi IFSB, IcedID and more.

What we find particularly interesting is the evolution of the social engineering tactics of BazarCall. With the growth in cyberattacks, people are increasingly aware of the common tactics used by adversaries. As awareness has improved, BazarCall has ceaselessly adapted and evolved its social engineering tactics accordingly.

These linked articles by Palo Alto Networks and Bleeping Computer can be referred to get information on the attack flow of some of the BazarCall campaigns.

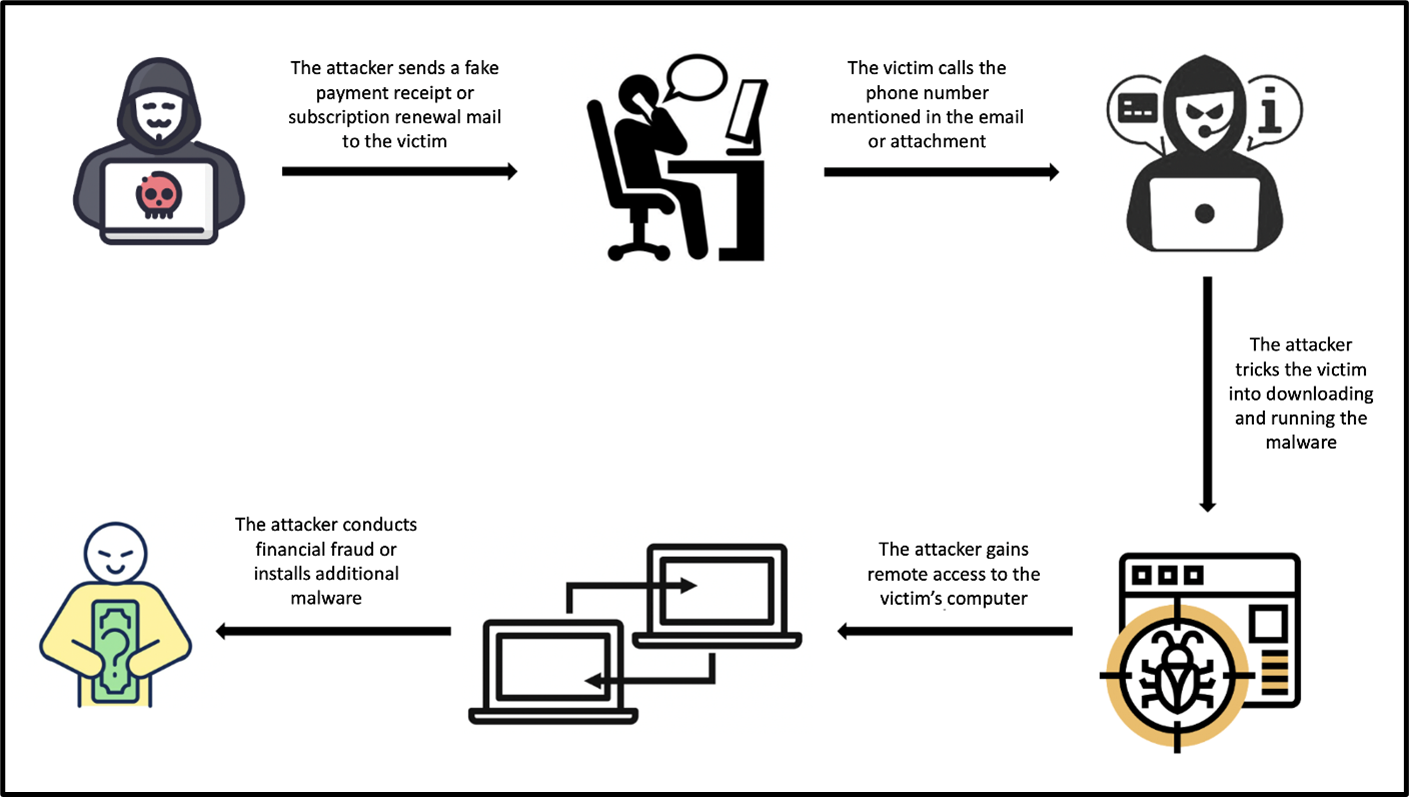

Analyzing the evolution

Using emails obtained by Trellix Email Security, our researchers contacted various call centers to learn about different techniques and tactics utilized by attackers. Based on the analysis, Trellix was able to generalize the attack flow of the BazarCall campaigns and categorize the same into three phases. The study also revealed the evolution of the social engineering tactics which was particularly noticed in the call center scripts used by the scammers to trick victims into downloading and installing malware in their system, the scammers are now found to be utilizing many different types of conversation scripts.

Let us dive into more details and go through the distinct phases of the attack.

Phase 1 - The bait

The delivery vector is a fake notification email which informs the recipient about a charge levied on their account for purchase/renewal of a product/subscription. It contains all the generic information like Product Name, Date, Model, etc. along with a unique invoice number used by the scammer to identify the victim. In addition, the email states that the victim can call the phone number for any queries or cancellation requests. In different variants, the information was found to be present in the email body or as a PDF attachment.

The campaign was seen impersonating many brands like Geek Squad, Norton, McAfee, PayPal, Microsoft etc. (listed in the order of popularity).

The following screenshots are some sample emails and attachments which were detected by Trellix Email Security being distributed in the wild.

Phase 2 - The attack

Once the recipient calls the scam call center the trickiest phase of the attack begins: manipulating the victim into downloading and running malware on their system.

BazarCall employs many different tactics to achieve this. We will now go into greater detail on the conversation script categories.

The (dis)honest guy

This tactic begins with the scammer asking victim for basic details like invoice number, phone number, email address etc. Following which, the scammer takes a pause and pretends to check his system to find any invoice relative to the details shared by the victim and then conveys that no invoice could be found. The scammer suggests that the email received by the victim is a spam email and should be ignored.

The scammer then queries victim to know if their system is slow or if they are facing any other issues with it, adding to which the scammer suggests that victim’s system might be affected with a malware which would have caused them to receive the spam email. He then offers to schedule a call back where an executive can scan and check the victim’s system and resolve any issues.

The next call begins with the scammer asking the name of the operating system which the victim is using. Following the answer, the scammer asks the victim to open a specific URL which is a malicious website masqueraded to look like a customer support website. The scammer then asks the victim to enter a code on the website to download a file which he claims to be an anti-virus software. As an additional tactic to make the call sound more authentic, the scammer asks the victim to keep a note of the code for verification purposes. Finally, the scammer asks the victim to execute the downloaded file to run the scan on their system.

The (fake) incident responder

This tactic was found to be used in PayPal themed BazarCall campaigns. It begins with the scammer asking the victim for the details like invoice number, debited amount etc. The scammer then asks if the victim uses PayPal, on answering “Yes,” the scammer then asks for the email ID which is linked to their PayPal account.

The scammer then pretends to check the information related to the victim’s PayPal account and states that the account has been accessed from 8 (or any random high number) devices. The scammer asks if all these devices belong to the victim and just like anyone would, the victim gets alarmed. The scammer then asks victim about their current location, following the answer the scammer informs the victim that their account was accessed from a suspicious location, the scammer would then name any random location which is far from the victim’s current location.

Now, something which we found amusing and interesting, the scammer asks the victim to search “What's my IP” on Google and suggests that if the result has a title as “your public IP address,” that means the connection is public and hence insecure. The scammer then suggests that to secure the connection, the victim would need to open a particular website. The final step is like the above case, where the scammer asks the victim to download and execute a file.

The over compensator

Just like the other categories, this tactic also begins with the scammer asking for basic details and pretending to check their system for the same. The scammer then confirms that the amount has been deducted from the victim’s account for the security (or any other) product. He then asks the victim if they would want to cancel the subscription and if the victim says “Yes,” the scammer explains the importance of security software to the victim and would ask if the victim still wants to proceed with the cancellation.

This is used as a tactic to make the call sound authentic by convincing the victim that the caller is motivated to sell the subscription for the security product and is rather not desperate to proceed for cancellation. The scammer then states that the victim needs to be connected to a support agent to complete the cancellation and receive a refund. As an additional tactic to gain trust, the scammer repeatedly asks the victim to not share any sensitive information with him as the call is being recorded and the company policy does not allow him to ask for any sensitive information from the customer. The final step is like the above case, where the scammer asks the victim to download and execute a file.

The (terr/sens)ible one

This tactic was found to be used in the “security subscription renewal” themed campaigns. This also begins with the scammer asking for some basic details and pretending to find information related to it. The scammer then explains to the victim that the charge has been levied on their account because the security product that came pre-installed with their laptop has expired and has hence been automatically renewed to continue the security protection for the device.

The scammer then asks the victim if they would like to continue with their security subscription or cancel it. As the victim requests to cancel the subscription, the scammer queries if the victim has any other security solution present on their system. This is also a trust-gaining tactic where the scammer pretends to be interested in the security of the victim’s system. The scammer then states that the victim needs to be connected to the cancellation server to complete the cancellation process and receive a refund. Here too, the final step is like the other cases, where the scammer asks the victim to download and execute a file.

The Relevance of the Invoice ID

You must have noticed that all variants of the campaign began with the scammer asking for the Invoice ID from the victim. That is because each Invoice ID is uniquely generated for every email. When the victim provides the Invoice ID to the scammer, the scammer searches for the same in their database and if found, the scammer can use details related to the Invoice ID in order to pretend to already have victim’s details like name, email address, amount debited, etc. This gives an impression of authenticity to the victim and helps to convince him into downloading and running the malware.

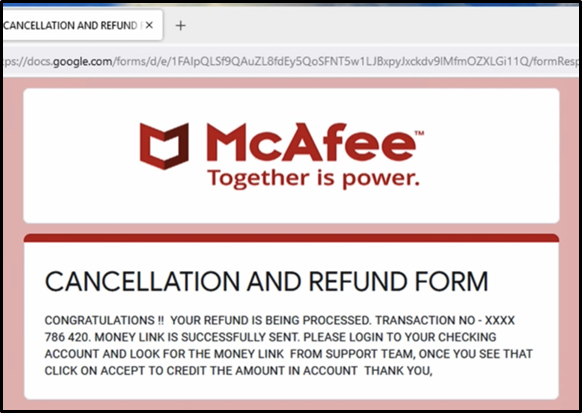

The following are some examples of the fake support websites found by Trellix Email Security which are being used in BazarCall campaigns to deliver the malware.

Phase 3 - The kill

Once the malware is executed, then begins the third phase of the attack where the malware is used to conduct financial fraud or push additional malware to the system.

Based on the analysis by researchers from Trellix, the majority of BazarCall campaigns utilize a file name like “support.Client.exe” and the following is an example of such a file spotted by our researchers:

Name

Support.Client.exe

Size

85.70 KB

File-Type

Win32 EXE

SHA 256

ead2b47848758a91466c91bed2378de1253d35db3505b5f725c289468d24645b

SHA 1

bc664ec8dff62f5793af24f6ca013e29498062f2

MD5

1e88b21d4c7d51f312337b477167ed25

On executing, the file connects to a malicious domain (in this case healthcenter[.]cc) and downloads a ClickOnce Security and Deployment Application file with “.application” extension. ClickOnce is a deployment technology that allows to create self-updating Windows-based applications that can be installed and run with minimal user interaction, you can read more about it here.

The malware then follows to drop multiple files on the victim’s system that are required for proper execution of the malware. The dropped files are found to be for ScreenConnect software which is a legitimate remote-control software by ConnectWise. Adversaries, however, have been utilizing ScreenConnect for many years as a part of the attack chain where to drop spyware, ransomware, etc. BazarCall campaigns have also been consistent with the use of ScreenConnect for more than a year.

Once the malware completes downloading the dependencies, it executes and the scammer gains remote access to the victim’s system. The attacker can also show a fake lock screen and make the system inaccessible to the victim, where the attacker is able to perform tasks without the victim being aware about them.the fourth page was the actual REvil backend panel as shared by the source.

In one such case noticed by Trellix, the scammer opens a Fake Cancellation Form behind the lock screen and then asks the victim to fill out the form that requires generic details like name, address, email, etc. On submitting the form, the victim receives a success message saying the refund is being processed and they should log into their bank account and accept the refund.

The scammer then asks the victim to login into their bank account to complete the refund process where the scammer would manipulate the victim into sending money to the scammer by making it look like as if the victim is receiving the amount. This is achieved by locking the victim’s screen and initiating a transfer-out request and then unlocking the screen when the transaction requires an OTP (One Time Password) or a secondary password. The victim is also presented with a fake refund successful page to convince him into believing that they have received the refund. The scammer may also send an SMS to the victim with a fake money received message as an additional tactic to prevent the victim from suspecting any fraud.

The above example only presents one of the many directions the attack can lead to, the attacker might also use the remote access to install additional malwares in the victim’s system to gain a persistent access to victim’s system which can be then used to spy on the activities, exfiltrate data, steal credentials or install a ransomware on the system.

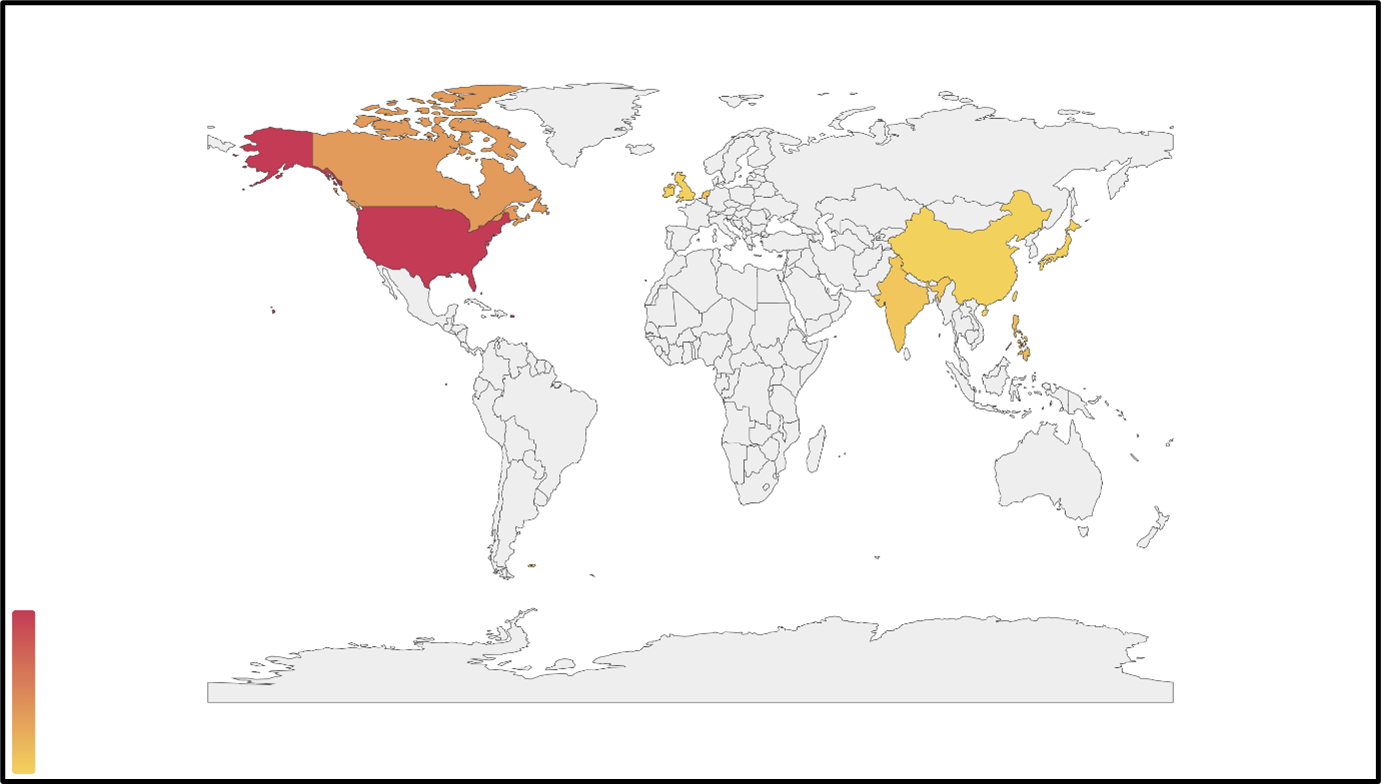

Infection map

The BazarCall campaigns were found to be most active in United States and Canada. They were also seen targeting some Asian countries like India and China.

Trellix protection

Trellix Email security provides reliable detection from BazarCall campaigns by preventing such emails from ever reaching your system. In addition to it, we also detect the campaign on other levels like network, URL and binary to provide complete protection to our customers.

The following are some of the many rules authored by us to detect such campaigns -

- EL_FRML_UNDIS_ORDER

- EL_GEEK_SQUAD_SCAM

- EL_VISHING_RCVD_FREEMAIL

- EL_GEN_SCAM_HUNT

- EL_VISHING_RCVD_ZERODAY

Indicators of compromise

The following link contains examples of malicious hosts used in the BazarCall campaigns

MITRE ATT<CK techniques

Within this campaign, we have observed the following MITRE ATT<CK techniques.

T1106

Native API

Adversaries may interact with the native OS application programming interface (API) to execute behaviors.

T1027.002

Software Packing

Adversaries may perform software packing or virtual machine software protection to conceal their code.

T1553.002

Code Signing

Adversaries may create, acquire, or steal code signing materials to sign their malware or tools.

T1112

Modify Registry

Adversaries may interact with the Windows Registry to hide configuration information within Registry keys, remove information as part of cleaning up, or as part of other techniques to aid in persistence and execution.

T1056.004

Credential API Hooking

Adversaries may hook into Windows application programming interface (API) functions to collect user credentials.

T1012

Query Registry

Adversaries may interact with the Windows Registry to gather information about the system, configuration, and installed software.

T1082

System Information Discovery

An adversary may attempt to get detailed information about the operating system and hardware, including version, patches, hotfixes, service packs, and architecture.

T1056.004

Credential API Hooking

Adversaries may hook into Windows application programming interface (API) functions to collect user credentials.

T1573

Encrypted Channel

Adversaries may employ a known encryption algorithm to conceal command and control traffic rather than relying on any inherent protections provided by a communication protocol.

T1113

Screen Capture

Adversaries may attempt to take screen captures of the desktop to gather information over the course of an operation.

T1563

Remote Service Session Hijacking

Adversaries may take control of preexisting sessions with remote services to move laterally in an environment.

This document and the information contained herein describes computer security research for educational purposes only and the convenience of Trellix customers. Trellix conducts research in accordance with its Vulnerability Reasonable Disclosure Policy. Any attempt to recreate part or all of the activities described is solely at the user’s risk, and neither Trellix nor its affiliates will bear any responsibility or liability.

RECENT NEWS

-

May 13, 2024

Seven Trellix Leaders Recognized on the 2024 CRN Women of the Channel List

-

May 6, 2024

Trellix Secures Digital Collaboration Across the Enterprise

-

May 6, 2024

Trellix Receives Six Awards for Industry Leadership in Threat Detection and Response

-

May 6, 2024

Trellix Database Security Safeguards Sensitive Data

-

May 6, 2024

92% of CISOs Question the Future of Their Role Amidst Growing AI Pressures

RECENT STORIES

The latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

We’re no strangers to cybersecurity. But we are a new company.

Stay up to date as we evolve.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.