Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

Akira Ransomware

By Max Kersten · November 29, 2023

This blog was also written by Alexandre Mundo

First discovered in early 2023, Akira ransomware seemed to be just another ransomware family that entered the market. Its continued activity and numerous victims are our main motivators to investigate the malware’s inner workings to empower blue teams to create additional defensive rules outside of their already in-place security.

EX/NX:

- FEC_Trojan_Win64_Generic_4

- Ransomware.Win64.Akira.FEC3

- Ransomware.Win.Akira.MVX

HX AV:

- Generic.Ransom.Akira.A.6926E830

- Generic.mg.f526a8ea744a8c50

ENS:

- AkiraRansom!F526A8EA744A

About Akira

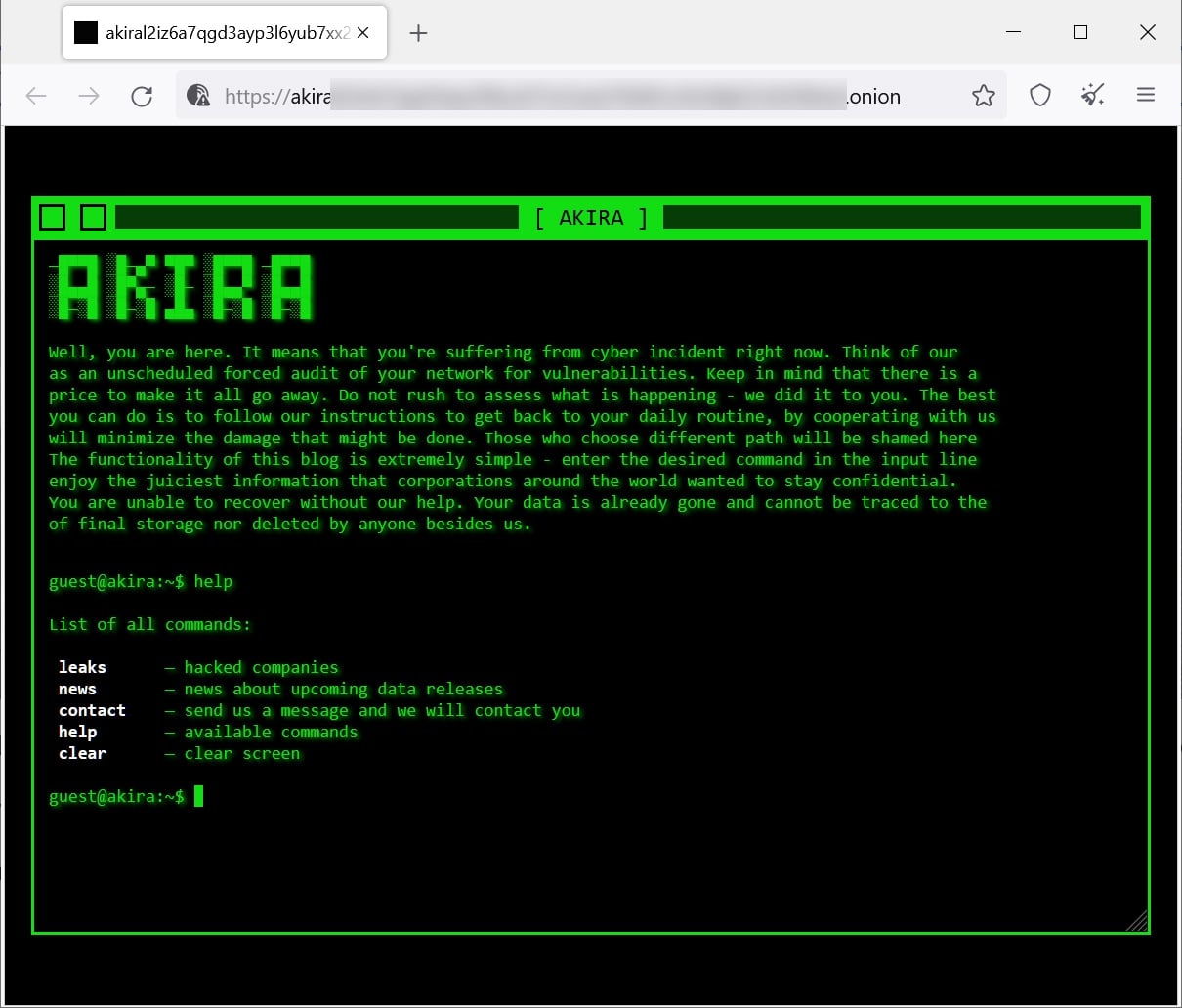

The ransomware’s name likely comes from an 1988 anime movie with the same name (spoilers ahead). The movie’s cyberpunk aesthetic is emulated by the ransom group on their leak site, as can be seen on the image below, courtesy of BleepingComputer.

The movie is set in Neo-Tokyo, which was built after Akira destroyed the city. In the movie, Akira destroys Neo-Tokyo in order to save the world from an ever growing mass of flesh within the city. The ransomware authors based their name on the powerful entity within the anime movie, or from its related manga, as they might perceive themselves as such.

The ransom group employs a double extortion scheme which includes exfiltrating data prior to the encryption of devices within the targeted network. As such, the ransom needs to be paid for the removal of the stolen files, which are otherwise leaked, and to obtain the decryptor to regain access to the encrypted files.

Victimology

Knowing if a group favors a certain sector, a geographical area, or acts purely based on opportunities is of great benefit for blue teams. It allows threat intelligence teams to understand their potential adversaries and act accordingly. Threat detection engineering teams and security operation centers can improve their detection based on known tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). Noteworthy here is that “known” TTPs do not necessarily mean publicly known, but rather internally known under any of the traffic light protocol’s options.

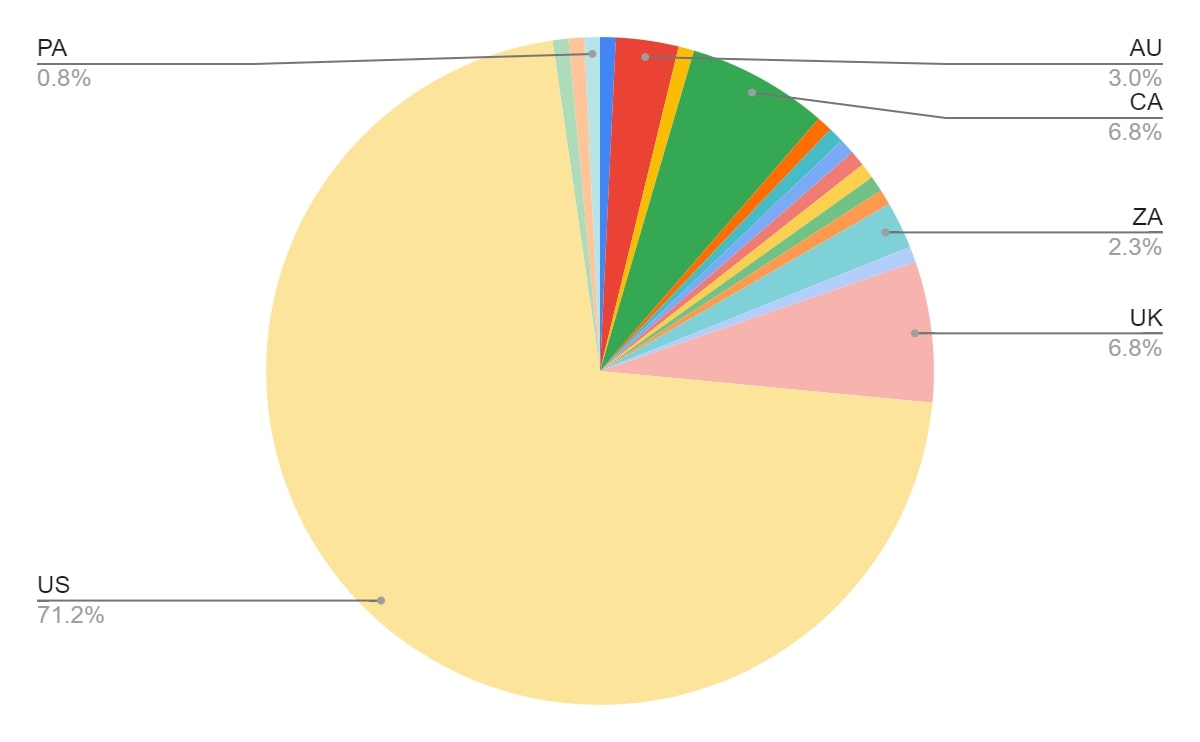

Akira’s victims, based on their blog posts, are plotted on the pie chart below. The country of origin of each company is based on the headquarters of the company, meaning that any company which has offices in multiple countries will only contribute to one country. A final note as to what counts as a victim in the numbers used in this blog: each unique company which has been published on Akira’s blog counts. Victims who do not show up on the blog, are not included.

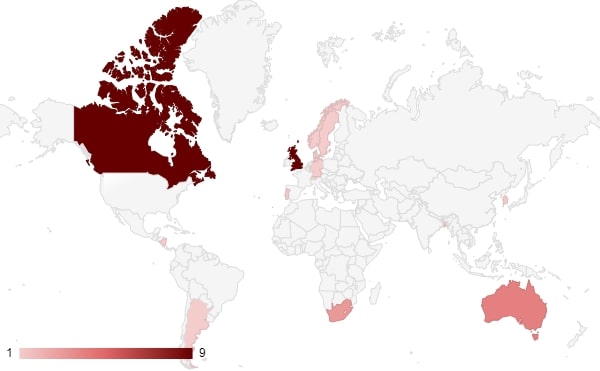

The overwhelming number of victims in the United States ensures that the color of any of the other countries remains low. Removing the United States from the data set provides a clearer picture of the rest of the victims, especially when plotted on a world map.

This shows that countries who are aligned with the United States (i.e. the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and South Korea) make up the majority of the victims on the list, aside from the United States themselves.

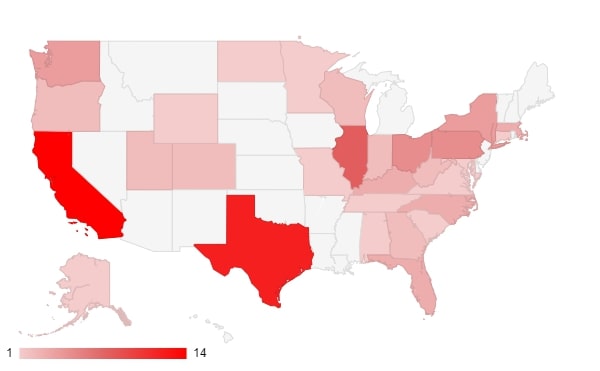

When looking at the U.S., one can plot the victims within the country per state. Similar to the way the countries are connected to a victim, the location of a company’s headquarters defines the listed state.

California and Texas are, respectively, the most populous states, which could be an explanation for the increased number of victims in those regions.

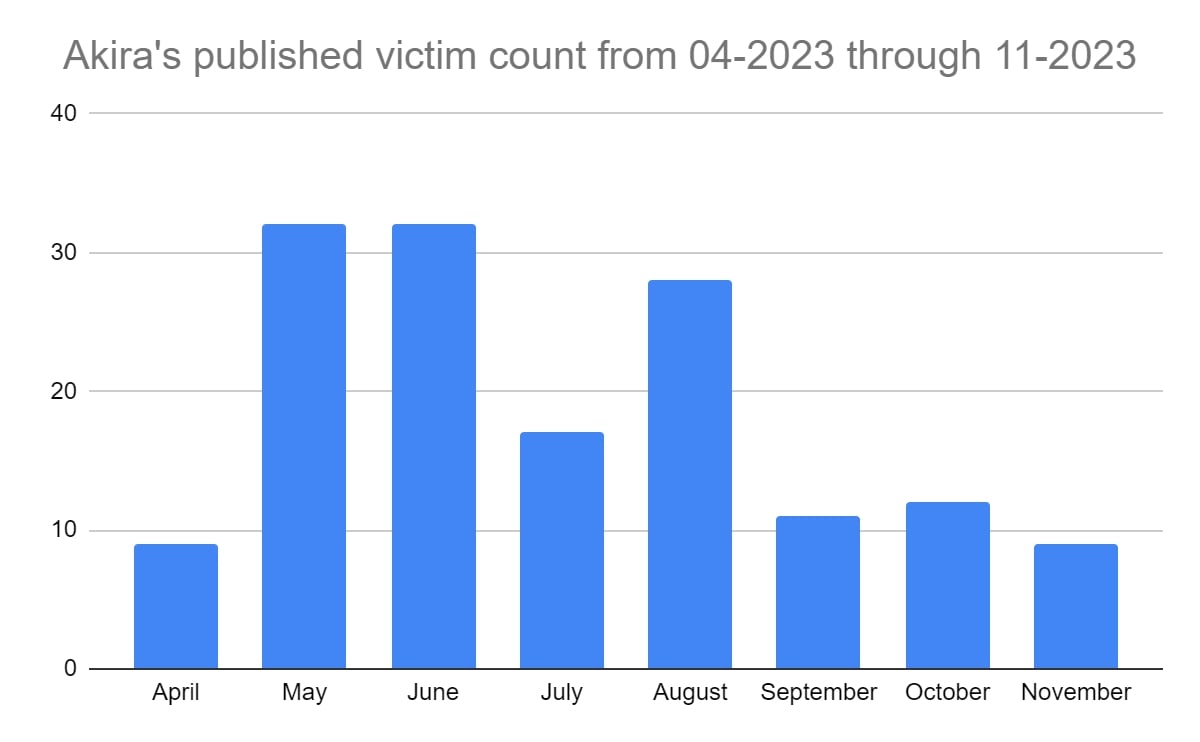

When plotting the frequency of the victims with data from April through October of this year, it shows May, June, and August as the busiest months for the blog. The cutoff date for the data is the 20th of November 2023. Do note that the victim count here is slightly higher, since some of Akira’s blogs were about the same company.

Even in ‘slow’ months, the group still averaged roughly 10 published victims. Since it is unknown how many victims there are in total, and how many of those victims pay, the number of published victims is not a definitive indicator as to how many victims were made overall.

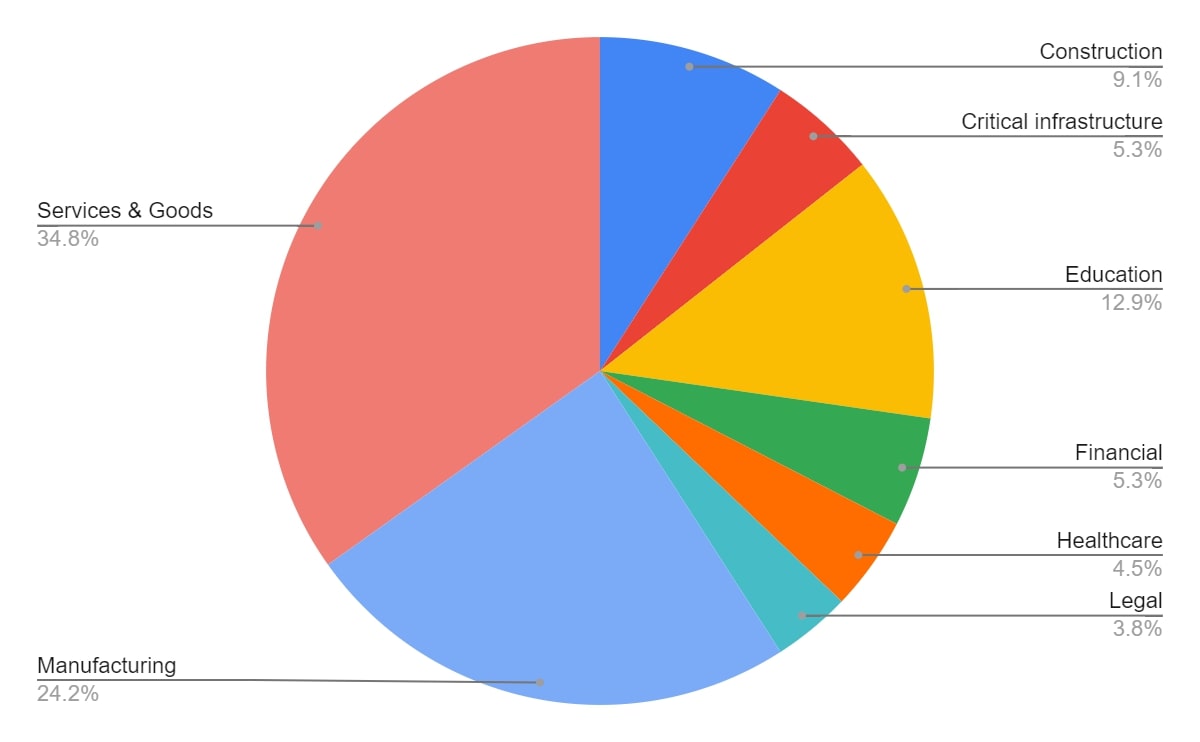

What is known about the published victims, is the primary sector of each company. Based on the names and manual verification, all sectors were mapped. For all victims in our data set, the following sectors were observed.

Notably here, are the major segments for services & goods, as well as manufacturing. Victims within the educational sector are often impacting thousands, since students are affected, as well as faculty staff. Critical infrastructure and legal are two sectors which might not make up a large portion of the victim base, but each victim contains a trove of information for attackers, and can impact the lives of many.

Known Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures

Note that ransomware groups often work with affiliates. These affiliates can work for multiple ransomware gangs at the same time. As such, there is no single set of TTPs which can define how the Akira ransomware can end up in one’s network. In this section, multiple sources will be used to provide a clear overview. The used sources are TrendMicro, SentinelOne, Sophos, DarkTrace, and LogPoint, along with Trellix’ comments and observations. Note that not all sources are used in each subsection.

For more information with regards to ransomware attacks, refer to our overview of common TTPs related to ransomware attacks.

Initial Access

The initial foothold on the system is obtained via several methods. Multi-factor authentication (MFA) exploitation (i.e. CVE-2023-20269) is mostly used in observed campaigns, along with known vulnerabilities in public facing services, such as RDP. Spear phishing is also used to gain a foothold, which is generally more effective than plain phishing, as it’s addressed to a specific user (group) and/or a relevant theme for the recipient(s).

Escalation and Lateral Movement

To escalate privileges and/or move laterally, LSASS dumps are used. Additionally, or alternatively, RDP is used to connect to other machines within the network while moving laterally. Other tools used are PCHunter64, LaZagne, and Mimikatz.

Data Collection and Exfiltration

Once the actors are in the system, data is exfiltrated by the actor. This way, the victim can be extorted twice: once to recover encrypted files, and once to ensure the stolen data is not made available publicly on the Akira extortion blog. To upload the gathered files, RClone, WinSCP, and FileZilla have been observed in use.

Technical analysis

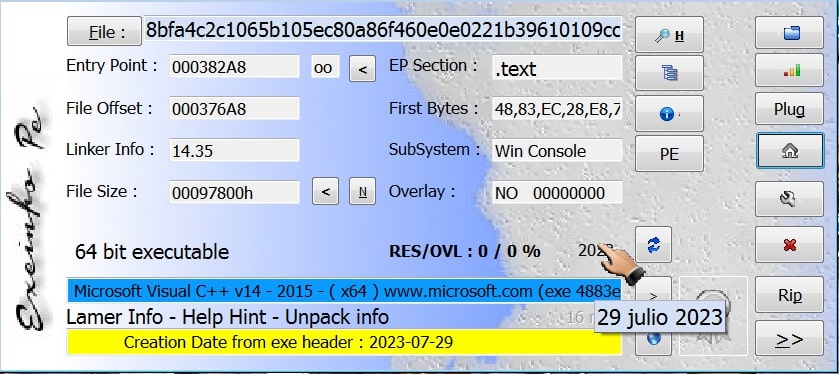

The malware is written in C++ and uses benign libraries. It is compiled for 64-bit Windows.

The compilation date of the analyzed sample is the 29th of July 2023, and it is a console application. Arguments to such an application are usually shared via the command-line and do not require a graphical interface of sorts.

Akira supports a number of arguments, which instruct the malware to execute certain functions. Below, the options are given.

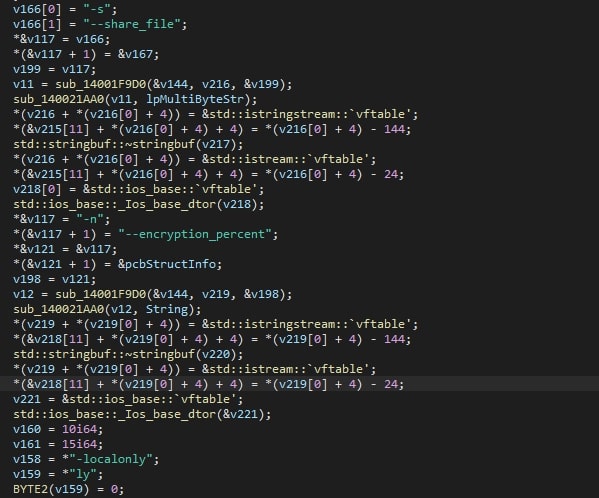

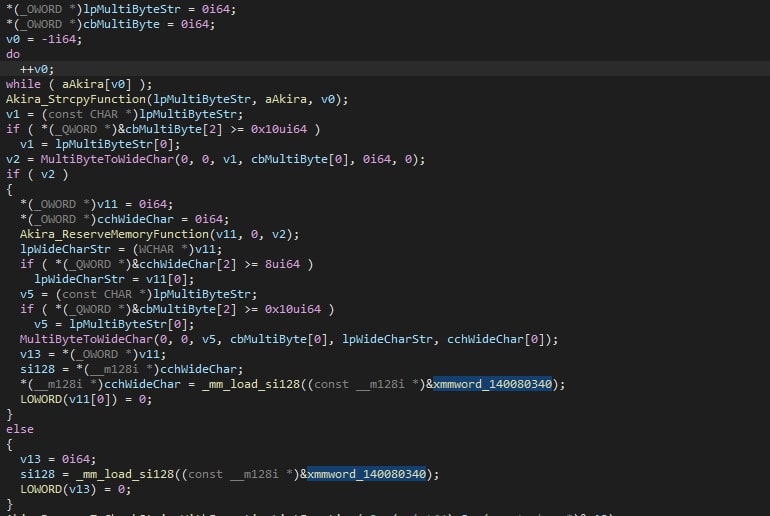

The code below shows how the command-line interface arguments are handled.

To encrypt files on the device, the ransomware requires a command-line interface argument for either a file path to start at, or a file which contains the paths to start at. Without either of these, the execution will only result in the creation of threads. If the file reference is provided but the path does not exist, an error will be shown and the malware will terminate itself.

At first, the “.akira” string, used as the file extension for encrypted files where it appended to the original file name and extension.

The malware excludes some file extensions, listed below, along with the “akira_readme.txt” file name to avoid encrypting the ransom note it drops.

- .exe

- .dll

- .sys

- .msi

- .lnk

- akira_readme.txt

Files with any other extension will be encrypted. Next, a PowerShell command is decrypted, and subsequently executed. The command is given below and is used to delete the shadow copies on the device. Shadow copies are used to restore files and could be used to restore encrypted files.

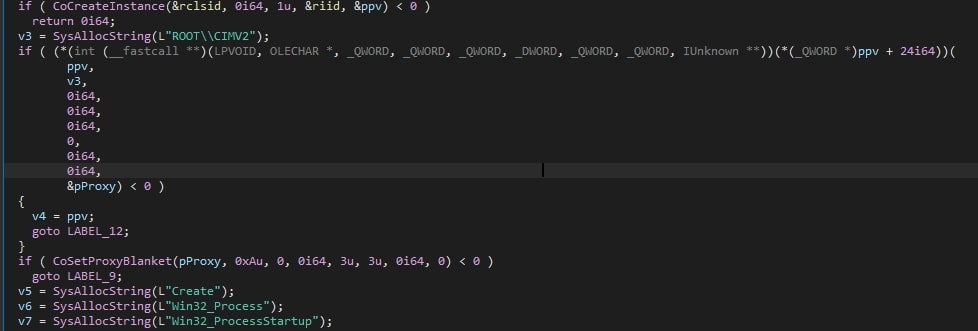

The command is executed with the help of COM objects to avoid being detected. The process ID (PID) of the newly created process is obtained and used to verify if the execution of the command was successful.

To ensure the shadow copies are deleted prior to moving on, the ransomware will use the previously obtained process ID, and wait 15 seconds. If no process ID can be obtained, it assumes the deletion has already finished, and the ransomware’s execution will proceed without waiting.

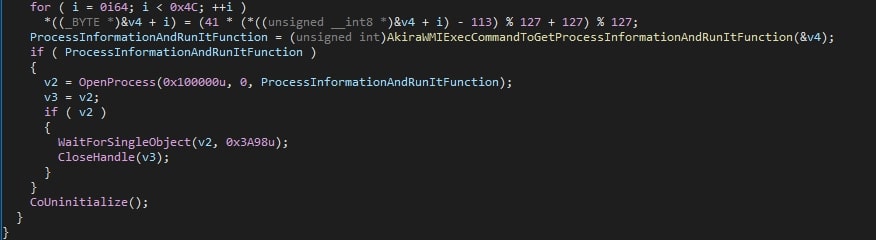

Using GetSystemInfo, the number of processors is obtained. This number is used to determine how many threads will be created. Way more threads than the number of processors will cause inefficient thread scheduling, and too few will not utilise the available number of processors. If the obtained number of processors is zero, the malware terminates itself.

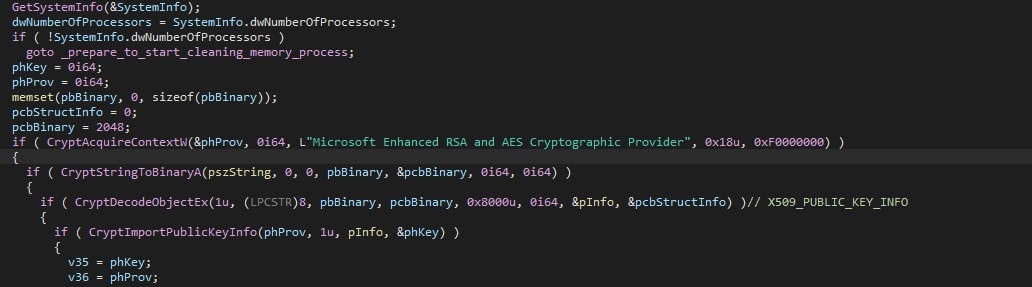

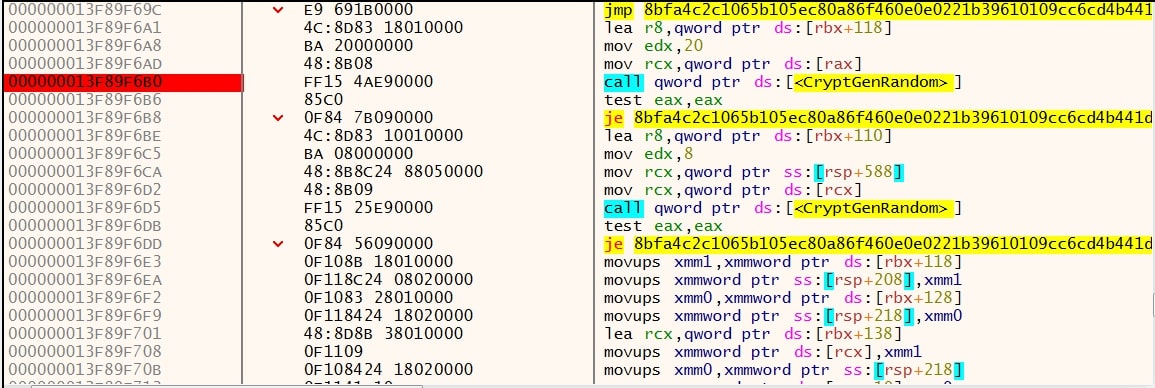

The encrypted embedded public RSA key is then decrypted using several WinAPI calls, starting with CryptAcquireContextW. This call returns a handler to the Windows cryptographic context. Using CryptStringToBinaryA, a given input string of a given format is converted into a byte string. The provided text in this case is “CRYPT_STRING_BASE64HEADER”. With CryptDecodeObjectEx, the final block is obtained, which is the decrypted public key. Said key is then imported using CryptImportPublicKeyInfo, ready to be used in the subsequent encryption process.

If the previously obtained number of processors is less than 4, the stored value will be set to 4 instead. As such, a minimum of four threads are created. Next, the key and IV are generated using CryptGenRandom, and a subsequent call to CryptEncrypt. This last sequence is also observed in Conti ransomware samples. To ensure the targeted file can be encrypted, the file’s attributes are read and checked using GetFileAttributesW. The file is accessed using CreateFileW, the size is obtained using GetFileSizeEx, and the used encryption algorithm is ChaCha. Again similar to Conti, the key and IV are encrypted with the ChaCha algorithm using the earlier decrypted RSA key.

This information is required to decrypt the file, which is done with a given or recreated decryptor. Additionally, the ransomware will leave ransom notes on the victim’s device, stating how to recover their files by paying the ransom.

Anatomy of an encrypted file

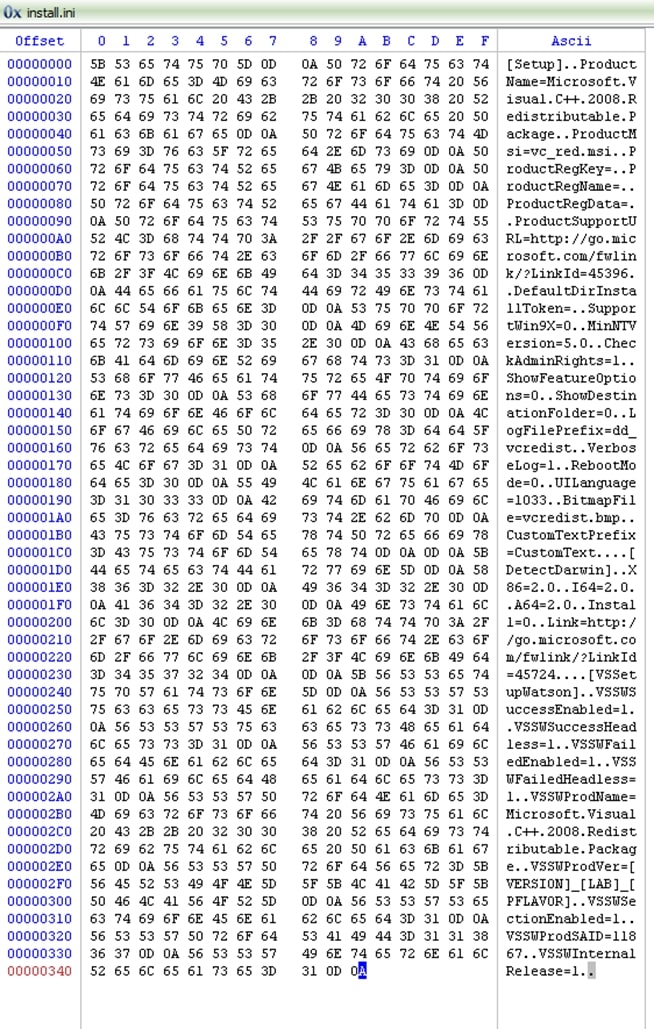

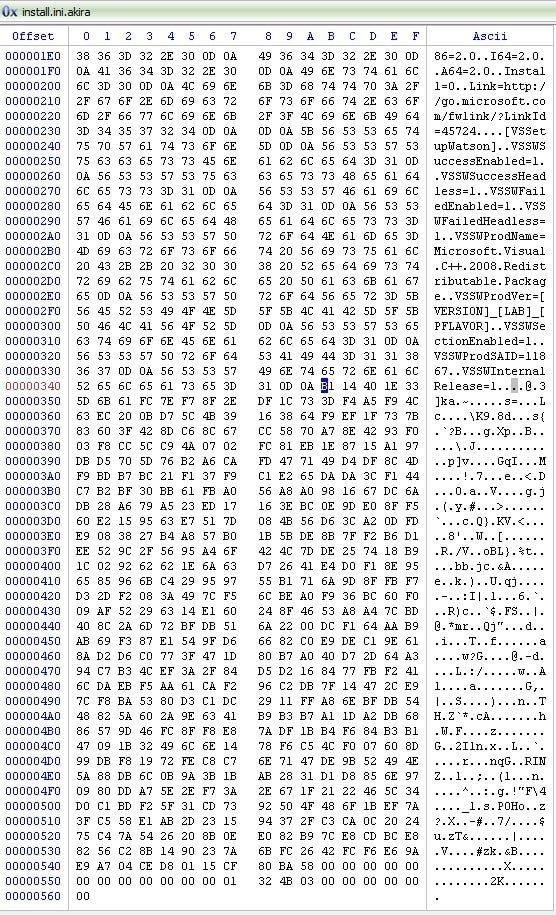

To illustrate the encryption mechanism of the ransomware, this section contains a sample file which has been encrypted. The sample file is plain text and has the “.ini” extension. Its size is 843 (0x34B) bytes in size. The encryption shows:

- Half of the file got encrypted

- The other half of the file remains untouched

- A block got added at the end of the file, containing the information required to decrypt said file

The file’s layout is as follows:

The following screenshot shows the original file:

The same file post encryption:

If the file is larger than 2 megabytes (based on 1000 bytes per kilobyte, and so forth, the total number of bytes is 2000000 in total), the malware will split the file in four blocks, where each block is partially encrypted. The goal here is to ensure that the file is unusable by the victim, while being able to encrypt more files per time unit, since files are only partially encrypted.

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques

Below are the relevant MITRE ATT&CK Techniques for the Akira ransomware.

RECENT NEWS

-

Jun 17, 2025

Trellix Accelerates Organizational Cyber Resilience with Deepened AWS Integrations

-

Jun 10, 2025

Trellix Finds Threat Intelligence Gap Calls for Proactive Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation

-

May 12, 2025

CRN Recognizes Trellix Partner Program with 2025 Women of the Channel List

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Details Surge in Cyber Activity Targeting United States, Telecom

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Advances Intelligent Data Security to Combat Insider Threats and Enable Compliance

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.