Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

Blurring the Lines: How Nation-States and Organized Cybercriminals Are Becoming Alike

By Tomer Shloman · January 7, 2025

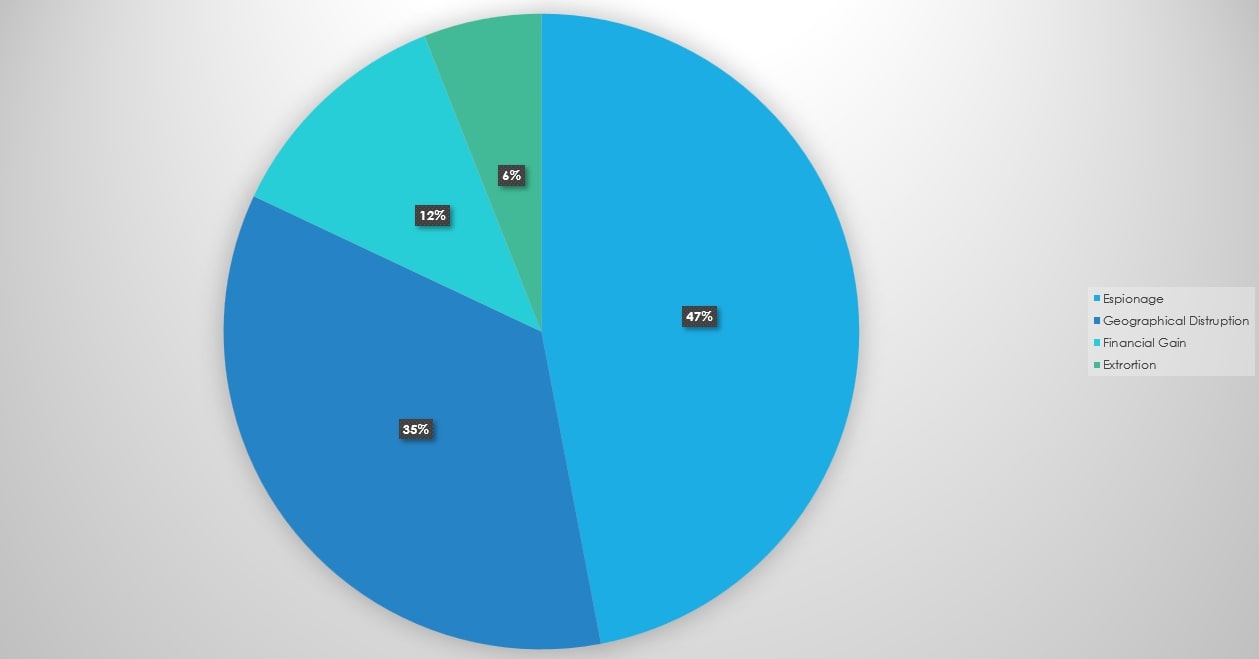

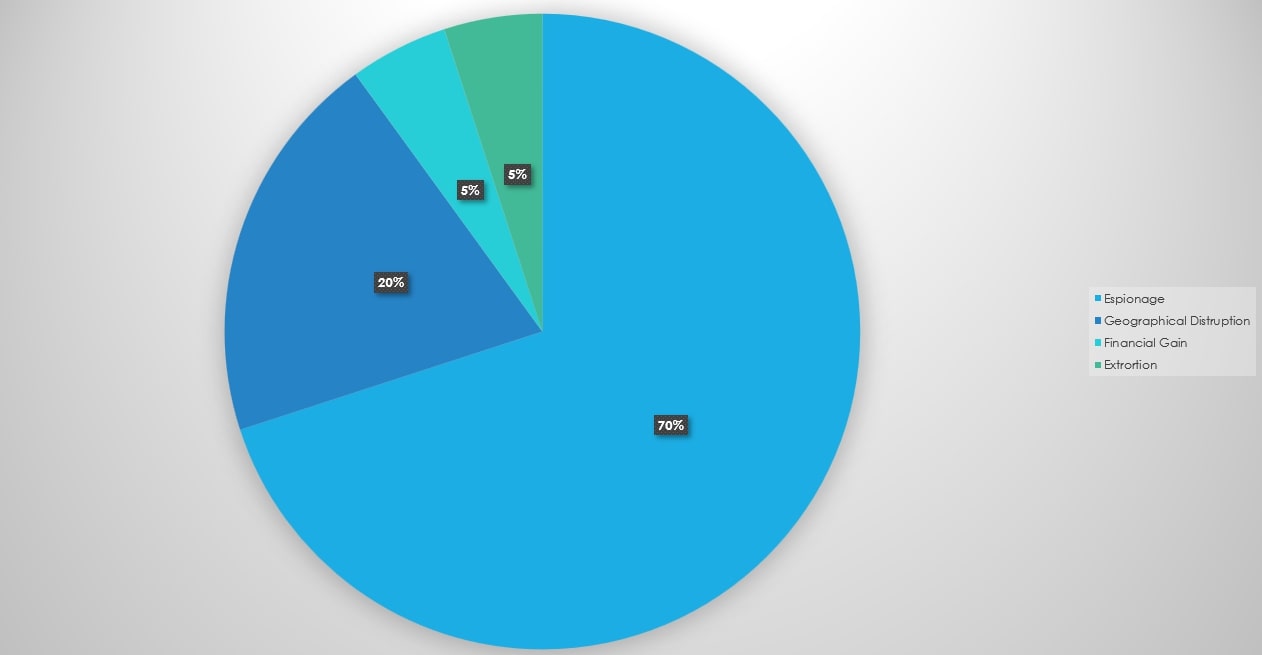

The distinction between nation-state actors and organized cybercriminals is becoming increasingly blurred in our rapidly evolving cyber landscape. Historically, these groups had distinct motivations: nation-states sought to achieve long-term geopolitical advantages through espionage and intelligence operations, while cybercriminals focused on financial gain, exploiting vulnerabilities for extortion, theft, and fraud.

However, recent evidence suggests an unsettling convergence of tactics, techniques, and even objectives, making it challenging to distinguish between them. This convergence not only complicates attribution efforts but also raises critical questions about the evolving nature of cyber threats and the implications for global security.

Nation-State Threat Actors: A legacy Of Geopolitical Ambitions

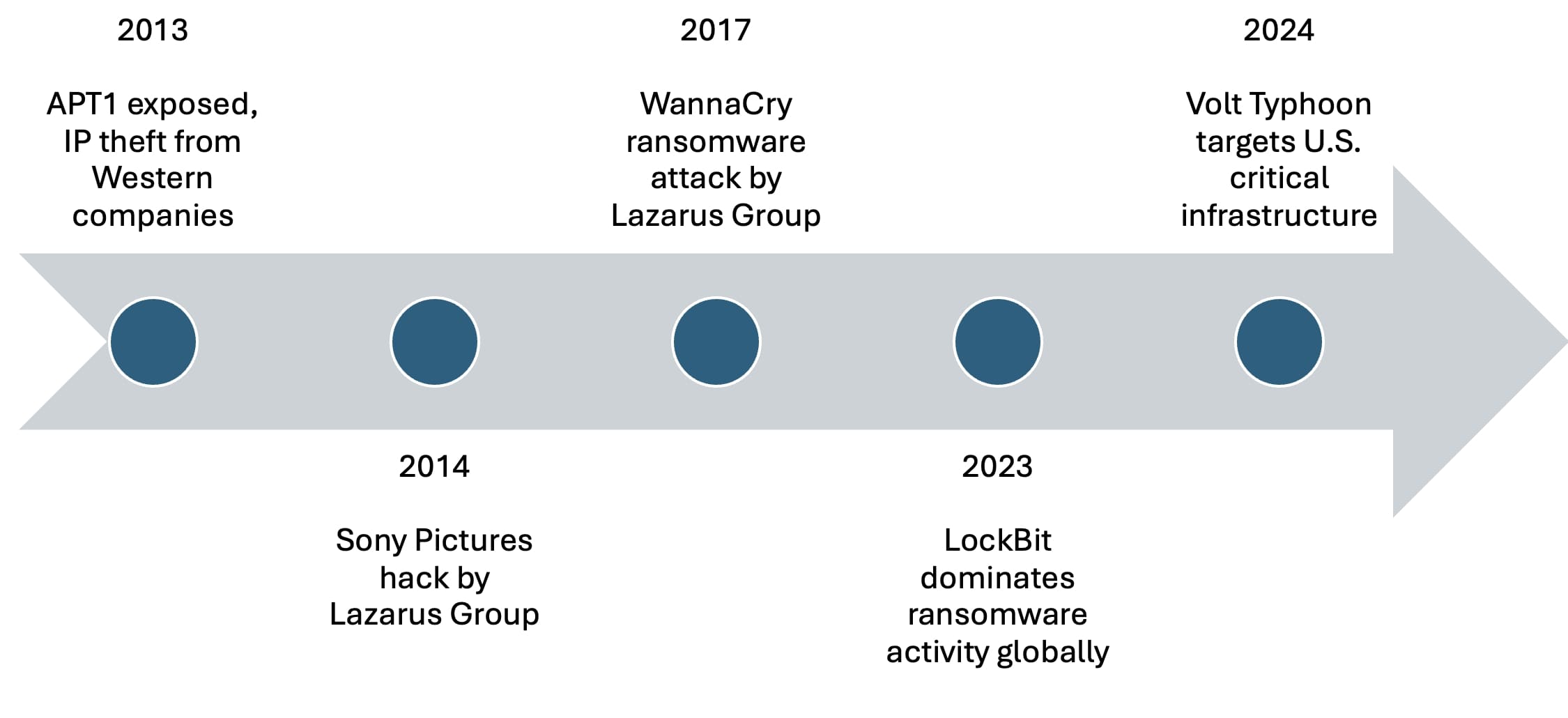

Nation-state actors such as China's APT10 and Russia's APT28, often regarded as some of the earliest and most prominent players, have targeted governmental, military, and critical infrastructure networks. Their objectives historically revolved around disrupting geopolitical rivals and gaining intelligence to maintain or enhance their countries' global influence. The sophistication of these early groups demonstrated the power of cyber operations as a strategic tool.

China has been a persistent and evolving force in the cyber domain. APT1 (also known as Comment Crew) was one of the first state-sponsored groups publicly exposed, with operations focused on stealing intellectual property from Western companies. In recent years, China’s Volt Typhoon has intensified its campaigns, targeting U.S. critical infrastructure sectors, such as manufacturing and transportation, using stealthy "living-off-the-land" techniques. Similarly, Salt Typhoon emerged as a significant threat in 2024, conducting espionage campaigns against U.S. telecommunications firms and potentially accessing private communications of American citizens.

Russia has also remained a dominant player, with groups like APT29 (Cozy Bear) conducting high-profile espionage activities against political entities and critical infrastructure in the U.S. and Europe. In 2024, Midnight Blizzard demonstrated Russia's continued focus on cyber operations when Microsoft disrupted a sophisticated attack by this group. Additionally, the clandestine Unit 29155, tied to Russia's GRU, highlights their hybrid approach, combining cyber and physical sabotage operations across Europe.

Iranian groups, such as APT33 and APT34 (OilRig), have demonstrated the state’s use of cyber capabilities to target critical industries like aviation, energy, and finance. These campaigns often serve to advance national interests and disrupt regional rivals. Recent reports indicate an increase in Iranian state-sponsored cyber-attacks on U.S. political entities during election cycles, aiming to influence outcomes and gather intelligence.

North Korea’s Lazarus Group has become infamous for merging traditional espionage with financial theft. Their operations—ranging from the 2014 Sony Pictures hack to the global WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017—underscore how some nation-state actors have evolved into hybrid entities. In 2024, they continued to target diverse sectors globally, blending geopolitical motives with financial incentives.

A critical emerging trend is the increasing collaboration between nation-state actors and cybercriminal networks, further blurring the lines between state-directed and criminal activities. This convergence complicates attribution and defense efforts, as these groups share resources, tactics, and objectives. The use of artificial intelligence by both attackers and defenders is also reshaping the cyber threat landscape, introducing new challenges and opportunities.

The evolution of nation-state threat actors from strictly geopolitical operations to hybrid models incorporating financial and criminal motives demonstrates the dynamic nature of the cyber threat landscape. As their methods and alliances become more sophisticated, the task of defending against such actors grows increasingly complex.

The evolution of nation-state threat actors from strictly geopolitical operations to hybrid models incorporating financial and criminal motives demonstrates the dynamic nature of the cyber threat landscape. As their methods and alliances become more sophisticated, the task of defending against such actors grows increasingly complex.

Organized Cybercriminals: Profit-Driven Exploitation

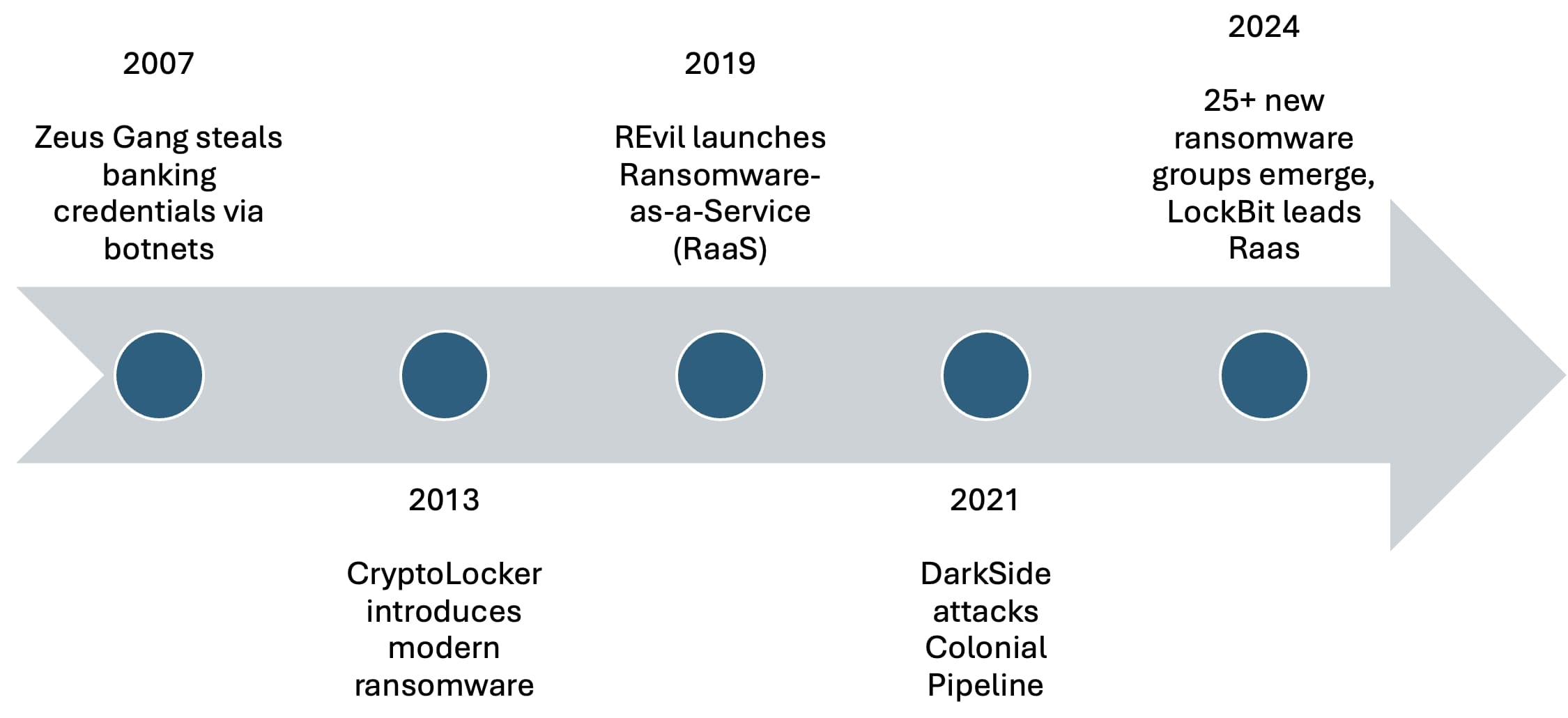

In contrast to nation-state actors, organized cybercriminals have evolved with financial gain as their core motivator. The early 2000s witnessed the rise of criminal organizations exploiting vulnerabilities for profit. Ransomware and data theft quickly became their primary tools, with groups such as REvil and DarkSide flourishing during an era when technology outpaced security. Their targets were corporations, financial institutions, and individuals—any entity that could be extorted for a payout.

Early pioneers of organized cybercrime included the Zeus Gang, which constructed one of the first large-scale botnets to steal banking credentials. Another notable group, Carbanak (also known as FIN7), specialized in sophisticated heists targeting financial institutions and point-of-sale systems, siphoning millions of dollars with remarkable precision.

Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) models revolutionized organized cybercrime, enabling groups like REvil (Sodinokibi) and LockBit to operate at unprecedented scales. LockBit, which remained the most prolific ransomware group into 2024, accounted for 24% of all recorded ransomware attacks in 2023. Similarly, DarkSide gained infamy with the Colonial Pipeline attack in 2021, illustrating how these groups could disrupt critical infrastructure and cause real-world consequences.

More recently, the BianLian group demonstrated the adaptability of cybercriminals by shifting from ransomware encryption to data theft extortion, reflecting evolving strategies aimed at maximizing payouts while evading detection. The first half of 2024 alone saw the emergence of at least 25 new ransomware groups, emphasizing the ever-expanding and dynamic nature of the threat landscape.

Adding to the complexity, cybercriminal networks have increasingly collaborated with nation-state actors, blurring the lines between financially motivated and state-directed activities. This convergence has made attribution more challenging and defense efforts more intricate. For example, the operational overlap between some ransomware groups and state-sponsored actors points to shared resources and mutual benefits.

Furthermore, artificial intelligence has emerged as a powerful tool for cybercriminals. AI is now used to create highly convincing deepfake content, automate phishing campaigns, and conduct large-scale reconnaissance, enabling attackers to carry out more sophisticated and impactful operations.

Organized cybercriminals have evolved from simple schemes to highly organized, global enterprises. Their ability to adapt, innovate, and exploit technological advancements ensures they remain a persistent and formidable threat in today’s cyber landscape.

A Gradual Convergence - When Espionage Meets Crime

As cybersecurity defenses have grown more sophisticated, the clear lines separating nation-state actors from organized cybercriminals have increasingly blurred. Nation state actors have adopted tactics once associated primarily with cybercriminals. Ransomware, a hallmark of organized crime, has found a new purpose in the hands of nation-states, used not only to disrupt services but also to generate funds for state-sponsored activities. For instance, North Korea’s Lazarus Group has seamlessly blended espionage with financial heists, including the infamous WannaCry ransomware outbreak that affected hundreds of thousands of systems globally. In 2024, North Korea’s Jumpy Pisces collaborated with the Play ransomware gang, illustrating direct partnerships between nation-states and cybercriminal organizations.

Similarly, Iranian state-sponsored actors have engaged in financially motivated ransomware attacks on U.S. organizations, blending espionage with profit-driven motives to support their geopolitical goals.

Conversely, organized cybercriminals have embraced more sophisticated techniques traditionally associated with nation-state actors. Advanced Persistent Threat (APT)-like tactics, including prolonged and stealthy network infiltrations, are increasingly evident in cybercriminal campaigns. Supply chain attacks—such as the REvil attack on Kaseya—have become a tool for maximizing the scale of operations. At the same time, advanced post-exploitation frameworks like Cobalt Strike, Metasploit, and Mimikatz enable cybercriminals to infiltrate networks with a precision once reserved for state-sponsored operations.

The convergence of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) between these groups reflects a complex and evolving reality. Both nation-state actors and cybercriminals exploit tools originally designed for legitimate security purposes. Cobalt Strike, for example, is used by Russia’s APT29 for espionage and by the Ryuk ransomware group for lateral movement within compromised environments. Similarly, Metasploit, a popular penetration testing tool, has been repurposed by both groups to exploit vulnerabilities and gain unauthorized access.

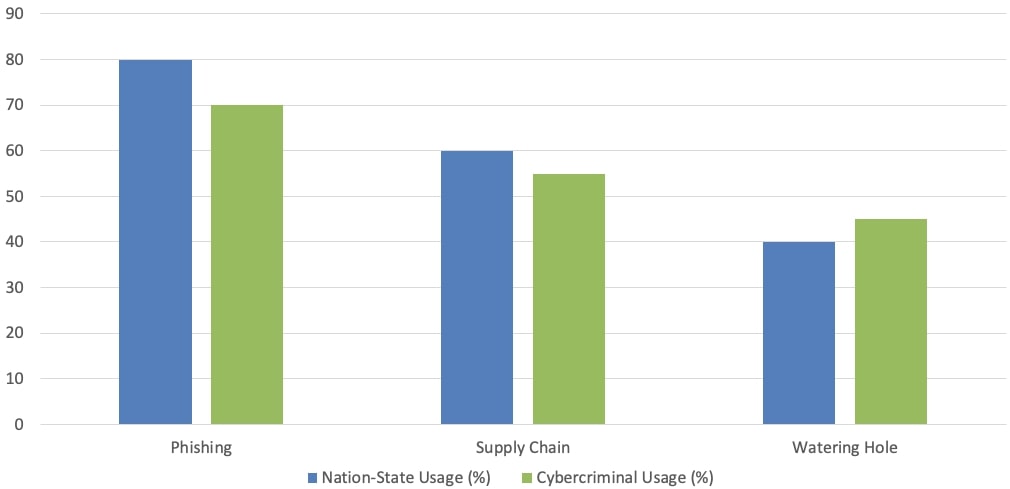

Common attack vectors further narrow the gap between these actors. Phishing, a favored tactic, is used by both sides: APT32 (Vietnam) might deploy spear-phishing campaigns against government entities and dissidents, while organized crime groups leverage the same technique to spread ransomware like LockBit. Supply chain attacks and watering hole attacks are equally adaptable, serving espionage or monetary gain depending on the actor’s objectives.

Both groups have also adopted advanced evasion techniques. Fileless malware, which executes code directly in memory to avoid traditional detection, has become increasingly prevalent. Living-off-the-land (LotL) tactics, where attackers exploit legitimate tools and processes already present on the target system, are now a standard feature of both nation-state and criminal campaigns. These techniques not only enhance stealth but also make attribution and mitigation more challenging.

Adding to the complexity, both nation-state actors and cybercriminals increasingly share resources and collaborate. In some cases, nation-states provide financial incentives to cybercriminals to conduct operations on their behalf, further intertwining their goals. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has also blurred the lines, as both groups leverage AI to enhance the scale and sophistication of their attacks, from automating phishing campaigns to creating highly convincing deepfake content.

This convergence between espionage and crime underscores the dynamic and interconnected nature of modern cyber threats. As nation-states and cybercriminals continue to adopt each other’s tactics, distinguishing between them becomes increasingly difficult—posing a growing challenge to global cybersecurity defenses.

TTP Convergence And Key Differences

The convergence of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) between nation-state actors and organized cybercriminals presents a complex challenge for cybersecurity defenders. While there is increasing overlap in the tools and techniques they employ, their underlying motivations, resource levels, and objectives remain distinct. In this section, we will explore both the similarities and differences between these threat actors, highlighting where their strategies align and where they diverge.

Evasion techniques

Evasion is key to avoiding detection, and both nation-states and cybercriminals use advanced techniques to remain under the radar:

- Fileless malware: Both actor types increasingly rely on fileless malware, where the malicious code is executed in memory, leaving no traces on disk. This approach is used by state-sponsored groups like APT34 (Iran) and cybercriminal groups such as FIN7.

- Living-off-the-land (LotL): Attackers from both categories use legitimate system tools to carry out malicious activities. For example, the WannaCry ransomware group utilized Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) for command execution, a technique also favored by APT groups to avoid detection by security solutions.

Shared command and control (C2) infrastructure

Nation-state actors and cybercriminals use similar methods for establishing and maintaining communication with their malware:

- Cloud-based C2: Cloud services such as Google Drive, AWS, and Dropbox have become favored channels for both actor types. These services are trusted by enterprises, making them effective for evading detection. Both APT41 (China) and cybercriminal organizations have used these platforms for data exfiltration and C2 communications.

- Encrypted C2 channels: Both groups use SSL/TLS encryption to protect their C2 traffic, making it more difficult for defenders to intercept and analyze communications between malware and its operators. This technique is used across the board by both state-sponsored APT groups and ransomware operators.

- Tor networks: Tor is frequently employed to anonymize C2 servers, and it’s favored by both cybercriminals and nation-state actors. The DarkSide ransomware group used Tor during the Colonial Pipeline attack, while multiple APT groups have employed it for espionage operations.

| TTP Category | Nation-State Actors | Organized Cybercrime | Convergence |

| Tools | Cobalt Strike, Metasploit, Mimikatz, Empire, BloodHound, LaZagne, Sliver, SharpHound, EternalBlue, HTran, PlugX | Cobalt Strike, Metasploit, Mimikatz, Empire, BloodHound, LaZagne, Dridex, TrickBot, Raccoon Stealer, AZORult | Both use the same off-the-shelf tools for post-exploitation and data collection. |

| Attack Vectors | Phishing, Supply Chain, Watering Hole, Exploit Kits (e.g., Angler, RIG), DNS Tunneling | Phishing, Supply Chain, Watering Hole, Exploit Kits (e.g., Angler, RIG), Brute Force, Credential Stuffing | Both use the same methods for initial access and delivery, with shared tactics evolving over time. |

| Evasion Techniques | Fileless Malware, LotL (e.g., WMI, PowerShell), DLL Sideloading, Process Injection, Obfuscated Scripts | Fileless Malware, LotL (e.g., WMI, PowerShell), DLL Sideloading, Process Hollowing, Encrypted Payloads | Similar evasion techniques to avoid detection and maintain persistence within targeted networks. |

| C2 Infrastructure | Cloud Services (AWS, Dropbox), Tor Networks, Bulletproof Hosting, DNS over HTTPS (DoH) | Cloud Services (AWS, Dropbox), Tor Networks, Bulletproof Hosting, Domain Fronting | Shared methods for establishing secure, anonymous C2 channels, utilizing cloud services and anonymity networks. |

Key Differences: Diverging Motivations And Objectives

Despite the convergence in TTPs, there are still critical differences between nation-state actors and organized cybercrime groups. These differences lie in their motivations, objectives, and targeting, all of which affect how these actors operate and what they aim to achieve.

Motivations

- Nation-state actors: These groups are driven by geopolitical objectives such as espionage, political disruption, and military advantage. APT29 (Russia), for instance, targeted the U.S. government and private companies for intelligence-gathering in the SolarWinds campaign.

- Organized cybercrime: On the other hand, cybercriminals are motivated almost exclusively by financial gain. Ransomware groups like REvil focus on extortion and fraud, prioritizing short-term monetary returns over strategic or political goals.

Targeting

- Nation-state actors: These actors typically focus on high-value targets aligned with their strategic objectives, such as government entities, military organizations, and critical infrastructure. The targeting is often covert and long-term, involving months or years of infiltration and data collection.

- Organized cybercrime: Cybercriminals cast a broader net, targeting industries with weaker defenses or high revenue potential, such as retail, healthcare, and financial services. Their attacks are typically opportunistic and focused on maximizing financial gains through ransoms or stolen data.

Resources and skill levels

- Nation-state actors: Backed by government resources, nation-state actors often have access to sophisticated cyber tools, intelligence assets, and a wide array of human resources. Their operations are usually more complex and involve custom-built tools designed for long-term operations.

- Organized cybercrime: Cybercriminals, while skilled, often rely on widely available commercial tools and frameworks. They operate with fewer resources than nation-state actors, frequently using ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) models that require less technical sophistication.

Objectives

- Nation-state actors: These actors aim to gather intelligence, disrupt geopolitical rivals, and achieve long-term strategic goals. For instance, North Korea’s Lazarus Group has engaged in both financial heists (e.g., the Bangladesh Bank hack) and politically motivated operations (e.g., the Sony Pictures hack).

- Organized cybercrime: Organized cybercriminals aim to make money as quickly as possible. Their objectives revolve around extortion, theft, and selling stolen information. They have little interest in the political ramifications of their actions unless there’s a direct financial incentive.

| TTP Category | Nation-State Actors | Organized Cybercrime | Key Differences |

| Motivations | Espionage, political disruption, military advantage, economic sabotage | Financial gain (ransomware, data theft, extortion), monetization of stolen data | Nation-states have strategic geopolitical motives, such as intelligence gathering, political influence, and coercion, while cybercriminals are profit-driven. |

| Targeting | Governments, military, critical infrastructure, key industries, political entities | Broad industries (retail, healthcare, financial), high-net-worth individuals, corporations | Nation-states target high-value, long-term espionage opportunities and sectors critical to national security, whereas cybercriminals focus on industries that can pay ransoms quickly. |

| Resources/Skill Level | State-sponsored, highly resourced, custom-built tools, intelligence assets | Rely on commercial tools, RaaS (Ransomware-as-a-Service), often less-resourced | Nation-states have state backing with access to intelligence and advanced capabilities, often creating customized tools for long-term infiltration. |

| Objectives | Long-term espionage, sabotage, disruption, geopolitical influence | Short-term financial gain, extortion, fraud, and black-market monetization of data | Nation-states aim for political, military, or strategic outcomes over extended periods, while criminals prioritize quick monetary returns. |

| Attack Vectors | Phishing, supply chain, watering hole attacks, zero-day exploits, hardware compromises | Phishing, supply chain, watering hole attacks, brute force, social engineering, exploit kits (e.g., RIG, Magnitude) | While sharing similar vectors, nation-states typically employ more sophisticated and multi-stage attacks with greater operational stealth. |

| Evasion Techniques | Fileless malware, Living-off-the-Land (LotL), obfuscation, rootkits, steganography | Fileless malware, Living-off-the-Land (LotL), off-the-shelf packers, dynamic payload delivery | Cybercriminals often rely on readily available evasion tools, while nation-states invest in bespoke solutions, including rootkits and hardware-level implants. |

| C2 Infrastructure | Encrypted channels, Tor, custom infrastructure, DNS tunneling, Domain Fronting | Encrypted channels, Tor, cloud services, Bulletproof hosting, Fast Flux networks | Cybercriminals often reuse existing C2 frameworks and rely on cloud services, while nation-states frequently develop custom solutions for added stealth. |

Motivational overlap

While the primary motivations of these actor groups remain distinct—espionage for nation-states and financial gain for criminals—there is increasing overlap in their objectives.

- Financial espionage: Nation-states such as North Korea’s Lazarus Group have engaged in financial espionage, conducting cyber heists to fund their national agendas. This blending of nation-state objectives with cybercriminal techniques is an emerging trend.

- Critical infrastructure attacks: Cybercriminal groups have begun targeting critical infrastructure with ransomware, a domain once reserved for nation-state actors. Attacks on the Colonial Pipeline and Irish Health Service highlight this trend, where financial motives coincide with broader geopolitical impacts.

- Ransomware in espionage: Some nation-states have begun deploying ransomware not only for financial gain but also to disrupt critical services in adversarial countries, blurring the lines between espionage and criminal extortion.

Geopolitical Influence on Cyber Operations and Sanction-Driven Attacks

In 2024, the geopolitical landscape plays a pivotal role in shaping cyber operations, with sanctions and trade wars fueling an increase in state-sponsored cyberattacks. Countries like Russia, Iran, and North Korea, facing economic sanctions imposed by the U.S. and its allies, have turned to cyberattacks as a means of counteracting financial isolation and resource deprivation. These sanctions cut off access to crucial resources, technologies, and financial markets, leaving the affected states with little choice but to leverage cyber operations as an alternative tool to achieve their political and economic objectives.

One prominent way sanctions influence cyber operations is through financial cybercrime. North Korea, under severe financial restrictions, has turned to cyber theft, particularly in the cryptocurrency space. Cyber groups like Lazarus have been linked to sophisticated attacks on cryptocurrency exchanges, where they steal digital assets to fund state activities, bypassing the financial constraints imposed by sanctions. Similarly, Russian cybercriminal groups, such as Conti, carry out ransomware attacks that bring in millions in ransom payments, which serve as a revenue stream for state-backed initiatives.

Sanctions have also led to a surge in intellectual property theft, as countries like China, restricted from accessing advanced technologies such as semiconductors, turn to cyber espionage. Chinese cyber actors target Western technology firms to steal proprietary designs and trade secrets, allowing the state to overcome trade restrictions and advance domestic innovation in key sectors like semiconductors, AI, and aerospace.

In retaliation for economic sanctions, states often launch cyberattacks targeting critical infrastructure in sanction-imposing countries. Russia, for example, has ramped up cyberattacks on the energy, financial, and healthcare sectors in Europe and the U.S., aiming to disrupt essential services, create economic instability, and pressure governments into reconsidering their sanctions policies. These retaliatory cyber operations highlight how sanctions can escalate geopolitical tensions into cyberspace, making critical sectors vulnerable to state-sponsored cyber threats.

The Challenges of Attribution

As the tactics of nation-state actors and organized cybercriminals converge, the challenge of attribution has become increasingly daunting. False flags, where clues are deliberately planted to mislead investigators, have emerged as a significant hurdle. In the lead-up to the 2024 Paris Olympics, cybersecurity experts warned of potential false flag operations, referencing the 2018 Pyeongchang Olympics attack, where Russian operatives allegedly planted evidence to implicate North Korea. These deceptive tactics further muddy the waters in identifying the true perpetrators of cyberattacks.

The reuse of malicious code adds another layer of complexity

Attackers frequently modify existing malware to suit their objectives, leading to similar code fragments appearing across unrelated attacks. This practice complicates attribution, as identical or near-identical code can be used by multiple actors with vastly different motives, making it challenging to pin down responsibility.

Shared infrastructure further blurs the lines between threat actors

Both nation-state groups and organized cybercriminals increasingly leverage common platforms such as Tor networks and encrypted command-and-control (C2) channels to anonymize their activities. This shared usage not only complicates attribution but also makes it more difficult for defenders to trace malicious traffic back to its origin.

The implications for cybersecurity are profound. Defenders must now contend with threats that look and behave similarly, regardless of whether they are driven by geopolitical ambitions or financial incentives. The focus must shift from attempting to attribute attacks to specific actors to developing more effective defenses that can counteract shared tactics and techniques. Behavior-based detection, robust threat intelligence, and proactive defense mechanisms are now critical to mitigating the risks posed by this increasingly complex threat landscape.

Conclusion

The convergence of nation-state actors and organized cybercriminals represents a transformative shift in the cyber threat landscape. These groups, once clearly delineated by distinct motivations and methods, are increasingly sharing tools, tactics, and even objectives, creating a gray zone where attribution becomes a daunting challenge. The use of AI, sophisticated evasion techniques, and overlapping attack vectors has blurred the lines further, making it imperative for defenders to adopt a behavior-based approach to detection.

This evolving landscape demands heightened vigilance, particularly for organizations in critical sectors. As hybrid threats become more prevalent, cybersecurity professionals must prioritize advanced threat intelligence, robust incident response plans, and proactive risk management.

Equally important is fostering international collaboration, as the global nature of these threats requires a united effort to counteract the increasingly indistinguishable activities of nation-states and cybercriminals.

Looking ahead, the convergence of these actors is likely to deepen, driven by geopolitical tensions, economic sanctions, and technological advancements.

While the attackers’ motives may blur, their capacity for disruption is unequivocal. The challenge for defenders lies not just in identifying the source of an attack but in building resilient systems capable of mitigating risks, irrespective of the perpetrator.

RECENT NEWS

-

Jun 17, 2025

Trellix Accelerates Organizational Cyber Resilience with Deepened AWS Integrations

-

Jun 10, 2025

Trellix Finds Threat Intelligence Gap Calls for Proactive Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation

-

May 12, 2025

CRN Recognizes Trellix Partner Program with 2025 Women of the Channel List

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Details Surge in Cyber Activity Targeting United States, Telecom

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Advances Intelligent Data Security to Combat Insider Threats and Enable Compliance

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.