Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

Turf Wars vs. Supply Chains: The Great Divergence in State Cyber Threats

By Ryan Slaney and Emma DeCarli · February 18, 2026

For years, the cybersecurity community has treated advanced persistent threat (APT) groups as monoliths. We assumed that if we found a specific Russian tool, we were fighting a specific Russian unit. If we found a Chinese web shell, we were fighting a specific Chinese bureau.

But as we look back on the 2025 threat landscape, a stark geopolitical divergence has emerged. The way our two primary adversaries—Russia and the People's Republic of China (PRC)—organize their cyber operations could not be more different. One resembles a chaotic, internecine turf war; the other, a hyper-efficient corporate supply chain.

This distinction is no longer merely an academic exercise; it is fundamental to effective modern network defense.

The Russian model: the game of thrones

Russian state-sponsored cyber activity is often defined by aggression, risk tolerance, and, surprisingly, internal competition. The Russian intelligence apparatus comprises powerful, overlapping agencies—primarily the GRU (military intelligence), the SVR (foreign intelligence), and the FSB (domestic security)—that constantly vie for the Kremlin's resources and favor.

This rivalry frequently spills over into cyberspace, resulting in messy, loud, and uncoordinated operations.

To augment this friction, the Kremlin often integrates a "shadow reserve" of criminal proxies and patriotic hacktivists. By leveraging hackers-for-hire like Aleksey Belan and Karim Baratov—or riding the coattails of "independent" ransomware groups—Russia gains a layer of plausible deniability and a loud, disruptive surge capacity that state agencies alone cannot provide. This stands in stark contrast to the PRC model, which avoids the volatility of independent criminals in favor of the controlled, corporate-state fusion seen in its "Digital Assembly Line.

The 2016 DNC hack

Perhaps the most famous example of this "turf war" model is the 2016 compromise of the Democratic National Committee (DNC). When CrowdStrike investigators analyzed the DNC network, they didn't just find one Russian actor; they found two.

APT29 SVR had quietly infiltrated the DNC’s network months earlier, stealthily exfiltrating intelligence for long-term espionage. However, APT28 then smashed into the network with aggressive tactics to steal the same data. Crucially, they were seemingly unaware of their SVR counterparts, effectively tripping over existing implants to rob the same house.

The chaos of the Russian model was further highlighted by what happened next. While the SVR likely intended to use the stolen intelligence for quiet diplomatic leverage, the GRU (APT28) chose to weaponize it immediately. In a hasty effort to mask their state affiliation and distract from the attribution to Russia, APT28 created the "Guccifer 2.0" persona, an homage to Marcel Lazăr Lehel, a Romanian hacker who went by the codename “Guccifer”. Lazăr was arrested in Romania in 2014 and later extradited to the United States. In 2016, he was sentenced to 52 months in a U.S. federal prison for hacking accounts belonging to U.S. politicians and their family members.

Using its newly created Guccifer2.0 persona, the GRU began dumping the stolen documents online. The fabrication was transparent—metadata analysis and linguistic slips quickly pointed back to Moscow—but it illustrates the fundamental nature of Russian cyber operations: they are often reactive, politically volatile, and willing to "burn" an intelligence source for immediate psychological impact. One agency was trying to listen; the other decided to blow up the building.

The Chinese model: the digital assembly line

Contrast the Russian approach with the PRC’s emerging operational model. The days of "smash-and-grab" intellectual property theft by rogue units are largely gone. Today, Chinese state cyber operations function like a well-oiled conglomerate, prioritizing specialization and collaboration over competition.

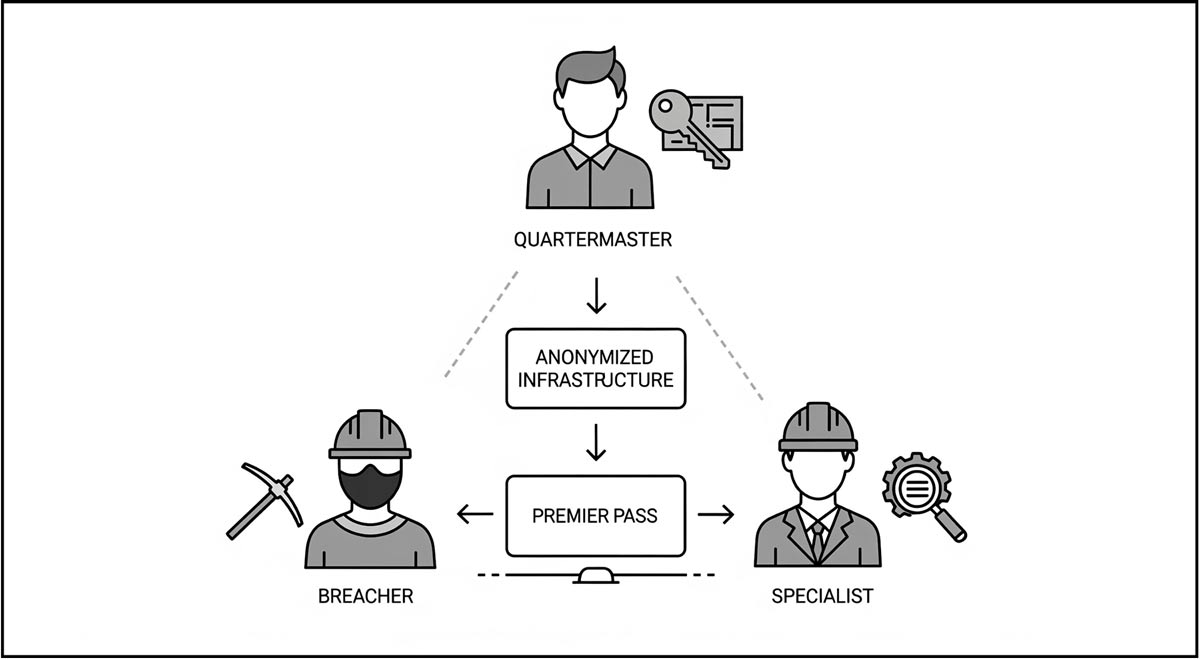

This "Digital Assembly Line" is composed of three distinct layers: The Quartermaster, the Breacher, and the Specialist.

Layer 1: The digital quartermaster

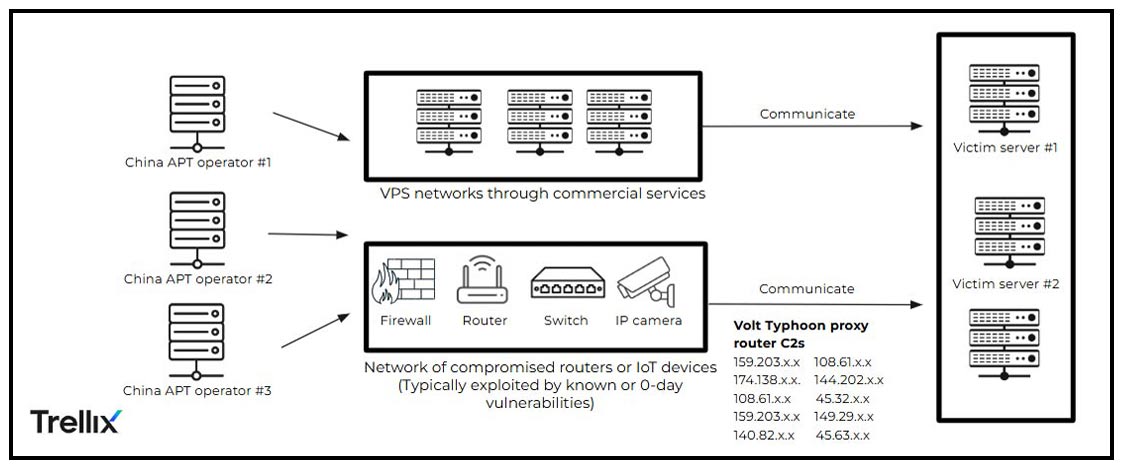

First proposed by Mandiant, the "Quartermaster" theory posits that Chinese espionage units no longer build their own infrastructure from scratch. Instead, just as a military quartermaster supplies uniforms and weapons so soldiers can focus on fighting, the PRC has centralized the procurement and development of cyber resources, including exploits and anonymization networks in the form of massive botnets built from compromised Small Office/Home Office (SOHO) devices.

For example, one of these massive botnets, Volt Typhoon's KV-botnet, is a sophisticated shared resource composed of compromised routers (Cisco, Netgear, and DrayTek) that routes malicious traffic through legitimate-looking residential IP addresses. KV-botnet is essentially "leased" to various PRC espionage groups who require its stealthy capability (hiding traffic within normal Western Internet activity) to facilitate their activities.

The Quartermaster theory doesn’t just apply to PRC’s intelligence services, as several Chinese companies and contractors are also known to contribute to the state’s pool of cyber resources. Perhaps the most vivid example of this corporate-state fusion is Raptor Train. This massive botnet, comprising over 200,000 compromised IoT devices (cameras, NVRs, and routers), is not run by a shadowy military unit, but by Integrity Technology Group (ITG)—a publicly traded cybersecurity company based in Beijing. ITG built Raptor Train to serve as an anonymization "highway" for state hackers. During the FBI's September 2024 takedown of Raptor Train, Integrity Technology Group actively fought back, launching a DDoS attack against the FBI’s remediation infrastructure in real-time. However, when they realized the network was lost, they "burned down" their own servers to destroy evidence.

Furthermore, recent leaks from Chinese firms like i-SOON and Knownsec have revealed a thriving "Hacker-for-Hire" ecosystem in which legitimate, office-based corporations with sales quotas and HR departments consider the development of tools used for cyber-espionage a "SaaS" (Stealth-as-a-Service) product.

The futility of "Whac-A-Mole" botnet takedowns

While Western law enforcement has achieved significant tactical victories, the strategic threat posed by the "Quartermaster" system remains undiminished. These efforts are often undermined by a fundamental reality: Law enforcement can remove the malware, but they cannot patch the hardware.

Therefore, in this ecosystem, network defenders are no longer just fighting malicious code; they are fighting the permanent state of an insecure internet. As long as these vulnerable devices remain online, the Quartermaster system can rebuild its inventory almost as fast as law enforcement can take it down.

Case Study: "Re-Infection Engines"

In January 2024, the FBI’s "Operation Dying Ember" disrupted the KV-botnet by remotely wiping malware from thousands of infected routers. However, because these devices were End-of-Life (EOL) and unpatchable, the "victory" was fleeting. Since the PRC’s Quartermaster system employs automated re-infection

Layer 2: The Breacher ("Premier Pass" - Phase 1)

In late 2024, Trend Micro formalized its "Premier Pass" theory to explain a disturbing trend: the separation of the burglar from the spy. This model describes a "hand-off" system where specialized China-aligned groups act as dedicated entry teams for downstream operators.

Groups like APT10, Mirrorface, and Earth Kasha utilize the Quartermaster's infrastructure (Layer 1) to scan the internet for vulnerable edge devices with surgical precision. Their goal is not necessarily to steal data, but to build an inventory. They aggressively exploit vulnerabilities to drop lightweight, "passive" web shells or create backdoors (such as Awen, Lodeinfo, or TrailBlaze). Once a device is compromised, it is "tagged" in a shared database categorized by sector (e.g., "U.S. Oil & Gas") and privilege level.

Essentially, under the Premier Pass model, the breacher uses the Quartermaster’s infrastructure to find and obtain the initial foothold and then "hands it over" to a mission-oriented group (e.g., APT5). The Breacher then moves on to the next target, leaving the door unlocked for the second team to conduct long-term espionage or pre-positioning.

By separating the initial breach from the actual mission, the Chinese state creates a "double blind." Even if a defender detects the Layer 3 operator, the original entry point was created by a different group using a different set of tools, making it nearly impossible for investigators to reconstruct the full lifecycle of the attack.

Layer 3: The Specialist ("Premier Pass" - Phase 2)

This is where the model becomes terrifyingly efficient. When the state requires intelligence on a specific target—say, a telecommunications provider or a defense contractor—they do not send the "noisy" brokers. They send specialists, like APT5.

APT5 is a significant strategic operator that focuses on the defense industrial base and telecommunications sectors. This group uses the "Premier Pass" model, which allows them to bypass the need for an exploit. Instead, APT5 simply queries the inventory, "checks out" access provided by Layer 2 brokers like Earth Kasha and APT10, and enters the network through already available access points.

APT5 is famous for "living in" the network appliance. They often use the pre-established access to modify VPN configurations or harvest credentials, allowing them to move laterally into the network disguised as a legitimate system administrator. Because they didn't break the lock themselves, they triggered almost no alarms during their entry.

Once inside, the specialist's goal is long-term presence, pre-positioning, and espionage. In late 2024 and 2025, specialists have been observed moving from IT environments into Operational Technology (OT) and Lawful Intercept (Wiretap) systems. By controlling the infrastructure that handles data, they can intercept private communications or prepare for future sabotage without ever deploying traditional, detectable malware.

The implications for defense

The shift from the "Russian Turf War" (where groups fought over access and left messy footprints) to the "Chinese Supply Chain" forces network defenders to change their calculus:

Specific attribution is tricky:

The detection of a web shell from a known "lower-tier" actor (like Earth Kasha) on an edge device should not be construed as a low-level threat. Rather, this may be the equivalent of a delivery driver who just dropped off a "Premier Pass" for a top-tier adversary like APT5.

Watch the handoff:

The most dangerous moment in an intrusion is no longer the exploit, but the handoff. Defenders must pivot from hunting malware to auditing configuration. Unauthorized VPN IP pools, new local user accounts, and inexplicable login anomalies are the smoking guns of a "Premier Pass" transfer.

The Edge is the front line:

The entire Chinese supply chain relies on the initial compromise of unmonitored edge appliances. If an organization is running EOL/vulnerable hardware on the perimeter, they are effectively volunteering to be part of the Quartermaster’s inventory.

Conclusion: a clash of doctrines

Network defenders are no longer simply defending against individual hacker groups; they are defending against distinct national doctrines, each with its own "personality" that dictates how it attacks.

While the Russian model is defined by aggressive, competing intelligence agencies fighting for dominance—often outsourcing the "dirty work" to a volatile mix of criminal hackers-for-hire and ransomware groups—other adversaries have carved out their own niches. North Korea, for instance, operates as a state-sponsored crime syndicate. Groups like Lazarus blur the line between espionage and bank robbery, targeting cryptocurrency and financial networks to fund the regime’s nuclear ambitions. Their hallmark is not subtlety, but desperate revenue generation. Iran, conversely, views cyber operations as a tool of asymmetric warfare and influence. Relying heavily on proxies and contractors, Iranian groups often focus on "hack-and-leak" operations or disruptive wiper attacks designed to signal strength and retaliate against regional rivals without triggering a kinetic war.

Yet, among these, the PRC model stands apart for its terrifying maturity. By industrializing their operations into a specialized supply chain—from the "Quartermaster" building the infrastructure to the "Breacher" cracking the door and the "Specialist" stealing the secrets—they have removed the friction that plagues their rivals. They have replaced ego with efficiency.

For network defenders, this is the critical lesson: You cannot defend against a supply chain by looking for a single exploit. You must defend against the system itself. PRC actors have learned that the most dangerous weapon in cyberspace isn't code. It's cooperation.

Discover the latest cybersecurity research from the Trellix Advanced Research Center: https://www.trellix.com/advanced-research-center/

RECENT NEWS

-

Mar 02, 2026

Trellix strengthens executive leadership team to accelerate cyber resilience vision

-

Feb 10, 2026

Trellix SecondSight actionable threat hunting strengthens cyber resilience

-

Dec 16, 2025

Trellix NDR Strengthens OT-IT Security Convergence

-

Dec 11, 2025

Trellix Finds 97% of CISOs Agree Hybrid Infrastructure Provides Greater Resilience

-

Oct 29, 2025

Trellix Announces No-Code Security Workflows for Faster Investigation and Response

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.