Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

From the Shadows to the Headlines: A Decade of State-Sponsored Cyber Leaks

By Ryan Slaney and Emma DeCarli · January 20, 2026

Executive summary

The December 2, 2025, publication of a massive leak revealing the inner workings of the IRGC-linked Department 40 (a.k.a. APT35, Charming Kitten, and Fresh Feline) has renewed global attention on the phenomenon of state-sponsored cyber disclosures. The leak, made public by UK-based opposition activist Nariman Gharib, claims to include real identities, organizational charts, operational orders, target lists, and evidence linking cyber activity to physical assassination plotting. This dramatic exposure provides a stark reminder that cyber leaks increasingly cross the boundary from technical exposure to human and operational unmasking. In light of this recent disclosure, we revisited a decade of major cyber leaks — from government programs to contractor firms and insider-driven exposures — to analyze motivations, patterns, and long-term impacts.

Historical leaks and disclosures

Over the last decade, a series of high-profile leaks have exposed state-sponsored cyber operations, including both government and contractor-led programs. Each leak differs in source, motivation, and impact, but together they illustrate how vulnerable sophisticated operations can be to insider compromise, investigative journalism, and targeted intrusion. As such, these leaks have forced operational resets, exposed personnel to personal risk and travel restrictions, provided actionable intelligence to rivals, and reshaped geopolitical perception.

One of the most consequential early examples was the Shadow Brokers incident (2016–2017), in which highly sophisticated NSA/Equation Group tools and exploits were stolen and released publicly. Although attribution has never been confirmed, theories range from a foreign intelligence service to a deeply embedded insider. The leak forced major operational changes within U.S. cyber units and demonstrated immediate real-world consequences when tools like ETERNALBLUE were repurposed by both nation-states and cybercriminals in attacks such as WannaCry and NotPetya. It remains the clearest example of a single cyber leak cascading into global geopolitical and economic damage.

Soon after, the 2017 “Vault 7” disclosure published by WikiLeaks exposed internal CIA documentation, development notes, malware frameworks, and tradecraft for multiple operational teams. Unlike Shadow Brokers, Vault 7 was ultimately attributed to an insider. In July 2022, former CIA software engineer Joshua Schulte was convicted of leaking the documents to WikiLeaks, and in February 2024, sentenced to 40 years' imprisonment. The impact was significant: not only did CIA operators have to rotate tools and operational techniques, but the leak also reignited debates around zero-day stockpiling, government cyber secrecy, and long-term internal controls required for intelligence agencies operating at scale.

Commercial and contractor leaks

Commercial offensive vendors have also been hit hard by leaks. Hacking Team, an Italian supplier of spyware sold to governments worldwide, suffered an external breach in 2015 that exposed internal emails, source code, financial records, and customer rosters. This immediately undermined its commercial credibility and provided journalists and security researchers with unprecedented insight into who was purchasing offensive capabilities and how they were being deployed, including sales to governments with histories of human-rights abuses. A similar event occurred in 2014 with the leak of Gamma Group/FinFisher material, including spyware source code and internal documentation. Widely believed to have been leaked by hacktivists rather than insiders, this disclosure gave defenders the ability to detect and reverse FinFisher implants more easily, while revealing the scale of the international intrusion-software marketplace.

Some leaks arrived through investigative reporting rather than raw data dumps. The 2019 exposure of the UAE’s “Project Raven” program relied on former operators speaking with journalists, revealing how ex-U.S. intelligence contractors were integrated into targeted hacking efforts against regional rivals, journalists, and dissidents. Rather than exposing toolchains, the reporting documented the increasingly blurred boundary between professional intelligence services and privatized offensive cyber firms, a trend that has raised policy and legal questions in multiple jurisdictions.

In 2021, the Pegasus Project disclosures again showed the power of journalistic collaboration. Rather than leaking malware source, the project analyzed internal datasets and target selections from NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware and confirmed widespread use of the platform against journalists, politicians, activists, and diplomatic targets. The fallout included global diplomatic backlash, sanctions, regulatory pressure, and reputational damage for the vendor and its customers.

Timeline of major leaks

2014 — FinFisher / Gamma Group documents leak. Source code and docs made public; researchers gained detection capability for a widely-sold commercial spyware.

2015 — Hacking Team breach. Full internal archives and customer lists published; exposed government customers and commercial spyware practices.

2016–2017 — Shadow Brokers releases. Multiple dumps of NSA/Equation Group tools; EternalBlue and others later used in large global incidents.

2017 — Vault 7 (WikiLeaks). “Year Zero” CIA document release revealing large CIA toolset and tradecraft; later led to prosecutions and major operational changes.

2019 — Project Raven reporting. Reuters/others revealed UAE program using ex-US operatives; raised contractor oversight concerns.

2020 — SolarWinds / SUNBURST aftermath research. Not a voluntary leak, but exposed attacker build artifacts that helped researchers understand supply-chain compromise methods.

2020 — BlueLeaks publication. DDoSecrets released law-enforcement caches; operational/policy fallout for many US agencies.

2021 — Pegasus Project reporting. Investigative consortium released targeting lists and analysis showing abusive use of NSO tooling by state customers.

2024 — i-Soon / Chinese contractor reporting & leaks. Reporting and leaked internal docs highlighted hacking-for-hire industry links to state tasks (journalistic investigations).

2024–2025 — Contractor/knownsec-style dumps (e.g., KnownSec). Multiple late-2024/2025 public exposures of contractor corp data and tooling showing the persistent risk from third parties.

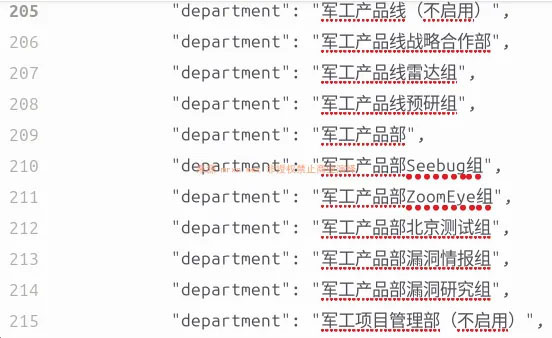

Chinese contractor leaks

More recently, the cyber contractor ecosystem in China has become a focal point for leaks. The i‑Soon/Anxun leak in early 2024 exposed internal documents, chat logs, technical manuals, and contracts from a firm deeply embedded in China’s state cyber apparatus. Leaked materials suggest i‑Soon provided tailored intrusion capabilities to multiple government bodies, including the Ministry of State Security and the Ministry of Public Security, and maintained dedicated teams for offensive operations and zero-day development. Employee chat logs reveal internal dissatisfaction and human factors that likely contributed to the leak. Analysts have tied parts of the leak to prior operations associated with APT41, illustrating that contractor data can reveal operational tooling, TTPs, and international targeting — in this case, spanning India, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. Shortly afterward, a separate KnownSec leak surfaced, including thousands of internal documents, source code for remote access tools, exploit frameworks, hardware-based attack designs, and detailed global target lists.

The Chinese contractor leaks illustrate the value of monitoring human risk factors, particularly in semi-commercial ecosystems, where internal grievances and operational dissatisfaction can materially increase the likelihood of leaks. They also highlight the need for segmented access control and zero-trust operational environments within contractor-managed systems.

Iranian insider leaks

On the Iranian side, the Lab Dookhtegan / Read My Lips leaks, which have been ongoing since 2019, systematically released operational tools, webshells, IP addresses, and even personal identifiers tied to APT34 (OilRig). The leaker, reportedly motivated by political or ideological factors, forced the group to rotate infrastructure and tools while simultaneously providing analysts with rich intelligence on Iranian cyber‑espionage tradecraft.

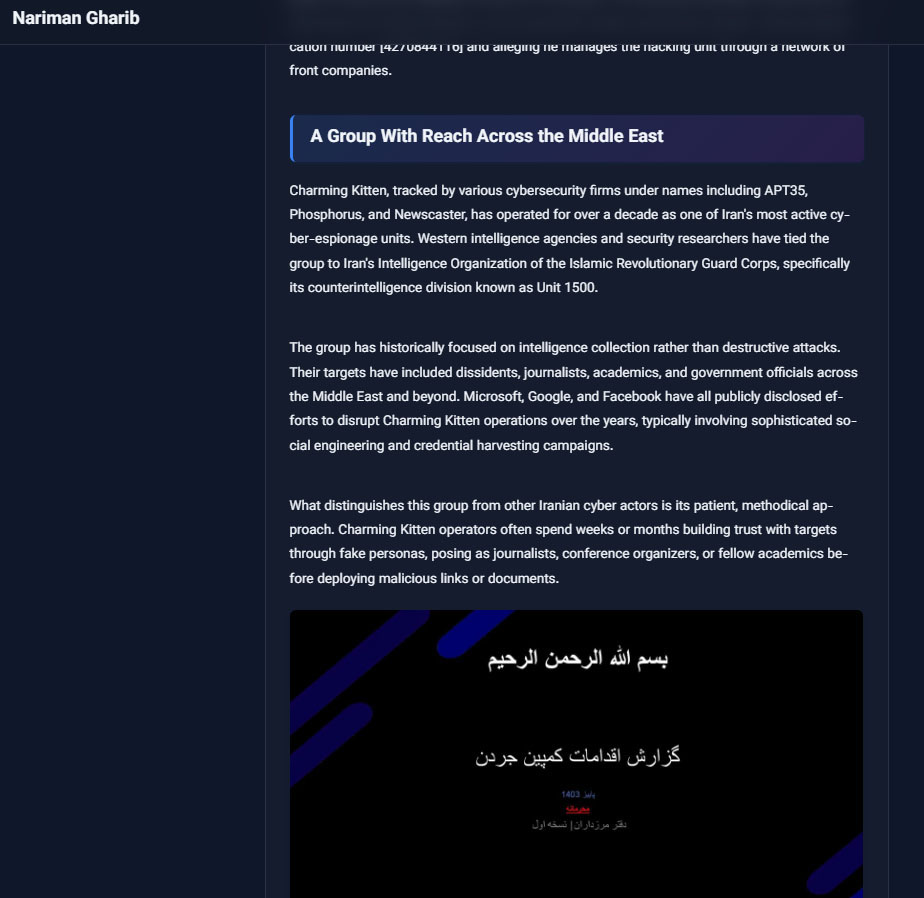

Similarly, the Nariman Gharib/KittenBusters leak disclosed internal Charming Kitten (APT35) communications, malware samples, Excel financials, operational logs, and even photographs of alleged operators. The materials revealed how Iranian operators organize phishing campaigns, allocate tasking by country, and report monthly performance metrics, exposing the quasi-commercial structure and bureaucratic operations behind state-aligned cyber activity.

These cases demonstrate that human motivation — including political ideology and personal grievances — can be a higher-value attack surface than the technical stack itself. Iran’s semi-commercial operational model, in which former intelligence officers go on to start companies that conduct cyber operations for the Iranian regime, further magnifies this risk, showing that internal access combined with ideological drive creates a potent vector for operational compromise.

Across all cases — from Shadow Brokers and Vault 7, to Hacking Team and FinFisher, to i‑Soon/KnownSec and Lab Dookhtegan/KittenBusters — common patterns emerge: insider threats, disgruntled personnel, and semi-commercial actors frequently magnify exposure risk. These patterns highlight the need for governments to integrate human, organizational, and technical security in tandem.

Why not Russia? Understanding the relative absence of Russian public cyber leaks

Unlike China, Iran, and even the U.S., Russia has not experienced major public-facing leaks of offensive cyber programs on the scale of i‑Soon, KnownSec, Lab Dookhtegan, or KittenBusters. Several factors likely contribute to this relative invisibility, spanning operational, cultural, and strategic dimensions.

First, Russian state cyber programs — including units tied to the GRU (APT28/Fancy Bear), FSB (Sandworm/Berserk Bear), and the SVR — are characterized by strong internal compartmentalization and operational security. Tooling, targeting lists, and personnel data are tightly siloed, with strict need-to-know protocols. Unlike Chinese contractor-based operations or Iranian semi-commercial teams, Russian units often operate using “air-gapped” or highly segmented infrastructure. This layered structure reduces the risk that a single insider could exfiltrate sensitive information, effectively lowering the likelihood of a leak reaching the public domain.

Second, Russia relies far less on private contractors or semi-commercial intermediaries for offensive cyber operations. Whereas China has used firms like i‑Soon and KnownSec to scale state campaigns, and Iran has leveraged internal operators and semi-commercial teams for APT34 and APT35 activity, Russia’s operations are largely conducted by state employees. Contractors are often the weakest link in operational security, both technically and in terms of loyalty; by keeping operations in-house, Russian programs reduce exposure to leaks.

Cultural and legal deterrents further reinforce this protective effect. The consequences for unauthorized disclosure in Russia are severe, ranging from criminal prosecution to personal risk (i.e., falling out a window), creating a strong disincentive for whistleblowers. Historical cases targeting cybersecurity professionals suspected of leaking sensitive information have amplified the perception that any leak carries extreme personal consequences, thereby suppressing insider motivation to expose operational data publicly.

There have been a few Russian leaks; however, these were primarily associated with influence operations rather than technical toolsets. Notably, the 2022 leak of the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA), or ‘troll farm,’ exposed payroll, organizational charts, and social media campaign planning. While this leak offered insight into coordination, staffing, and targeting, it did not include offensive malware or exploit toolchains, illustrating the difference between administrative leaks and technical compromises.

Strategically, Russian cyber doctrine emphasizes deniability, precision, and long-term campaigns. Their operations tend to be smaller in observable footprint but highly targeted, contrasting with the distributed, contractor-heavy operations seen in China or the semi-commercial teams of Iran. Fewer operational copies, centralized tool storage, and strict internal controls mean there is simply less material available for potential insiders to leak.

Finally, it is also possible that leaks have occurred but remain classified or suppressed, accessible only to intelligence agencies or cybersecurity firms. Unlike i‑Soon or KittenBusters, where materials were made publicly available on GitHub, X/Twitter, or other forums, any Russian leak may be tightly contained, preventing public dissemination and media coverage.

Overall, Russia’s relative absence from large-scale technical leaks likely stems from tight compartmentalization, minimal contractor involvement, strong insider deterrents, deliberate operational segmentation, and potential suppression of sensitive material. When Russian actors are ‘doxxed,’ it typically occurs only after formal indictment by foreign authorities — for example, in U.S. and European prosecutions following the 2016 election interference and NotPetya attacks — rather than through voluntary disclosure or insider leaks.

Actor doxxing: Personal risk and strategic consequences

One of the most profound and often overlooked effects of cyber leaks is the doxxing of individual operators. Unlike leaks of tools, infrastructure, or operational plans, doxxing exposes personal identifiers — names, photographs, email addresses, employment history, and sometimes home addresses — making individual personnel vulnerable to arrest, sanctions, or targeted surveillance.

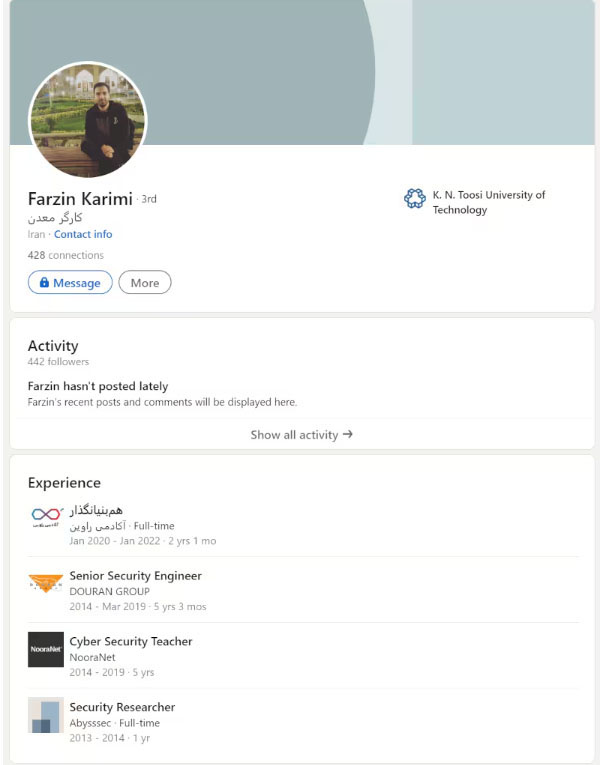

For instance, the Lab Dookhtegan / Read My Lips leak systematically released the identities of Iranian APT34 operators, alongside photographs and role assignments. Similarly, the KittenBusters / Nariman Gharib leak included internal documentation linking Charming Kitten (APT35) operators to specific campaigns and personnel metrics. These personas have been particularly hard on some former members of the Iranian intelligence services who have gone on to start a cybersecurity training school called Ravin Academy, even releasing pictures of Farzin Karimi, the school’s founder and president, as well as other key staff members.

In contrast, Russian actor doxxing is largely indirect. Public identification usually occurs only when individuals are formally indicted by foreign governments or exposed through investigative journalism connecting them to operations — such as GRU officers involved in NotPetya, SolarWinds, or election interference campaigns. This means that Russian operators typically retain anonymity in day-to-day operations unless legal action or investigative scrutiny arises.

The consequences of such doxxing are immediate and tangible. Individuals linked to leaked campaigns may be effectively confined to their home countries, as traveling abroad carries the risk of detention, arrest, or extradition. In some cases, doxxed actors may face financial sanctions or targeted counterintelligence operations. Beyond the personal impact, doxxing also serves as a strategic tool: it publicly undermines the perception of anonymity that state cyber operators rely on, creates diplomatic tension, and may deter insider participation or recruitment.

From an operational perspective, doxxing also forces states to reassign, retrain, or replace affected personnel, compounding the operational costs of the original leak. It demonstrates that modern cyber conflict extends beyond infrastructure or malware: human operators themselves are high-value assets whose exposure can have legal, diplomatic, and operational consequences.

In short, actor doxxing adds a human layer of risk to cyber leaks. While infrastructure and malware can be replaced or rotated, personnel cannot. The combination of public exposure, international legal frameworks, and media reporting makes doxxing one of the most strategically disruptive outcomes of cyber disclosures.

Impact of leaks on nation-state cyber programs

The leaks of offensive cyber programs over the past several years have had material operational, strategic, and geopolitical consequences, often extending far beyond immediate technical disruption. One of the most apparent effects is the forced rotation of tools, infrastructure, and tradecraft. Leaks such as Lab Dookhtegan targeting Iran’s APT34, the KittenBusters / Nariman Gharib disclosures on APT35, and the i‑Soon and KnownSec contractor leaks in China have compelled operators to rebuild malware families, replace command-and-control infrastructure, and reestablish operational security procedures. These resets consume development cycles, manpower, and budget, increasing the operational cost of offensive cyber programs. In the case of China, the contractor-based leaks also illustrate that exposure is not limited to state systems; third-party firms are high-value targets whose compromise can have cascading effects on state cyber operations. Similarly, the Iranian leaks demonstrate that even highly disciplined state teams are vulnerable when insiders or politically motivated actors share operational or personal information publicly.

These incidents emphasize that insider risk is a critical operational consideration. For contractors and semi-commercial entities like i‑Soon or Iranian operational cells, disgruntled staff or politically motivated insiders can create systemic vulnerability. Proactive human monitoring, behavioral analytics, and insider threat mitigation are as essential as technical defenses.

Beyond immediate operational loss, these leaks have provided a significant intelligence windfall. The i‑Soon and KnownSec disclosures revealed internal business models, toolkits, zero-day capabilities, and global targeting data, while the Iranian leaks offered insight into task allocation, organizational structure, and tradecraft for both APT34 and APT35. Analysts can now link malware and infrastructure to real-world operators, assess targeting priorities, and evaluate operational efficiency. In some cases, leaked artifacts were directly correlated to prior campaigns, confirming attribution and improving the defensive posture of affected targets. For example, analysis of i‑Soon’s internal communications connected certain toolchains to APT41 campaigns in Southeast Asia, while KittenBusters material revealed Charming Kitten’s multi-national phishing campaigns and internal metrics for operator performance.

Strategically, these leaks affect diplomatic and political standing. By exposing the human and technical layers behind offensive operations, leaks like Lab Dookhtegan, KittenBusters, i‑Soon, and KnownSec erode the plausible deniability that states and their contractors rely upon. They also raise questions about the role of private firms in enabling state cyber operations: i‑Soon and KnownSec demonstrate how contractor ecosystems can act as force multipliers for state activity but simultaneously serve as high-risk vectors for exposure. For Iran, the publication of operator photos and personal identifiers amplifies reputational and operational risk, highlighting how politically or ideologically motivated insiders can impose strategic costs without direct foreign intervention.

Iran’s semi-commercial model creates a unique vulnerability. Bureaucratic documentation, performance metrics, and task allocation procedures, while improving operational efficiency internally, simultaneously provide a rich dataset for adversaries if exposed. This human-centered exposure magnifies the impact of leaks beyond technical loss, affecting strategy, diplomatic posture, and personnel management.

Finally, these leaks illustrate broader systemic vulnerabilities in offensive cyber operations. Both the Chinese contractor leaks and the Iranian insider-driven disclosures show that offensive cyber capability is not only a technical domain but a human and organizational one. Weak controls, disgruntled personnel, and insufficient separation between operational and administrative duties can create cascading exposure risks. These events highlight that maintaining operational secrecy is increasingly dependent on managing personnel, contractors, and semi-commercial entities as carefully as one manages malware and infrastructure. The integration of these insights into defensive planning and policy-making is essential: while the technical artifacts themselves provide tactical advantage, the lessons learned about organizational structure, human risk, and contractor reliance are equally strategic.

A key lesson across all cases is that organizations must assume that all tools and information may eventually become public. Pre-emptive operational planning should include contingencies for tool rotation, rapid infrastructure rekeying, secure retirement of C2 systems, and compartmentalization to limit single points of failure. Operational resilience is no longer just technical; it requires proactive human, organizational, and procedural safeguards.

Furthermore, governments and private entities must prepare public affairs, legal, and diplomatic playbooks before leaks occur. Reputational and political fallout often precedes technical mitigation, particularly when leaks involve journalists, foreign governments, or civil society targets. Rapid, coordinated messaging and crisis management are critical components of operational resilience in the modern cyber ecosystem.

Taken together, the i‑Soon, KnownSec, Lab Dookhtegan, and KittenBusters leaks underscore the multiple dimensions of risk inherent in modern offensive cyber operations. They demonstrate that while state and semi-state actors can scale their capabilities through contractors and sophisticated toolsets, these advantages carry inherent vulnerabilities. Leaks disrupt operations, expose personnel, provide actionable intelligence to rivals, and reshape geopolitical perception, emphasizing that the consequences of disclosure are as much organizational and strategic as they are technical.

In summary, mitigating the impact of cyber leaks requires a holistic approach: integrating human risk monitoring, compartmentalized operational design, pre-planned response protocols, and assumptions of tool loss into both offensive and defensive cyber doctrine.

Conclusion

The decade of state-sponsored cyber leaks detailed in this analysis—from Shadow Brokers and Vault 7, to the commercial compromises of Hacking Team and NSO Group, and the more recent insider exposures of Chinese (i-Soon, KnownSec) and Iranian (Lab Dookhtegan, KittenBusters) operations—paints a clear picture: the organizational and human vulnerabilities inherent in offensive cyber operations are now the primary vectors for catastrophic public disclosure.

Crucially, the factors driving these leaks are systemic and show no signs of abating. As long as nation-states rely on contractors and semi-commercial entities to scale their cyber power (as seen in China and Iran), the risk of disgruntled, underpaid, or poorly vetted personnel remains high. Similarly, as long as political, ideological, or moral disagreements persist within intelligence services, the threat of the politically motivated insider (as seen with Vault 7 and Lab Dookhtegan) will endure. These human-centered motivators—dissatisfaction, political dissent, and personal grievance—are the underlying fissures that technical security measures alone cannot fully seal.

Therefore, the only reasonable conclusion is that leaks of this nature will continue. Every time a collection of operational data, toolkits, or internal chat logs surfaces, a global audience is waiting: network defenders gain immediate, actionable intelligence to improve their defenses; eager cybersecurity professionals use the artifacts for research and attribution; and adversary nation-state actors benefit from the forced operational resets and intelligence windfalls. The cycle of compromise, disclosure, and exploitation has become a permanent feature of the geopolitical landscape. For those charged with offensive cyber operations, the challenge is not to prevent leaks entirely, but to build organizational resilience around the inevitability of human and technical failure.

Discover the latest cybersecurity research from the Trellix Advanced Research Center: https://www.trellix.com/advanced-research-center/

RECENT NEWS

-

Mar 02, 2026

Trellix strengthens executive leadership team to accelerate cyber resilience vision

-

Feb 10, 2026

Trellix SecondSight actionable threat hunting strengthens cyber resilience

-

Dec 16, 2025

Trellix NDR Strengthens OT-IT Security Convergence

-

Dec 11, 2025

Trellix Finds 97% of CISOs Agree Hybrid Infrastructure Provides Greater Resilience

-

Oct 29, 2025

Trellix Announces No-Code Security Workflows for Faster Investigation and Response

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.