Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

Technical Deep Dive: The Monero Mining Campaign

By Aswath A · February 17, 2026

Executive summary

In the contemporary threat landscape, while ransomware grabs headlines with high-impact disruptions, cryptojacking operations have quietly evolved into sophisticated, persistent threats. This report details a comprehensive forensic analysis of a recently identified cryptocurrency mining campaign. This operation distinguishes itself not merely by its payload but by its high level of technical integration and redundant persistence mechanisms.

Analysis of the recovered dropper, persistence triggers, and mining payload reveals a sophisticated, multi-stage infection prioritizing maximum cryptocurrency mining hashrate, often destabilizing the victim system. Furthermore, the malware exhibits worm-like capabilities, spreading across external storage devices, enabling lateral movement even in air-gapped environments.

This blog dissects the malware operation from the initial social-engineering lure to the execution of privileged instruction sets in Ring 0, offering a granular view of the attackers’ tradecraft, tooling, and operational security posture.

1. Introduction: The evolution of commodity cryptojacking

Cryptojacking, the unauthorized use of a victim's computing resources to mine cryptocurrency, has transitioned from a browser-based nuisance (typified by Coinhive scripts) to a system-level threat utilizing advanced malware techniques. The economic incentives for attackers are clear: unlike ransomware, which requires a victim to pay, cryptojacking generates revenue continuously as long as the infection persists. To maximize this revenue, attackers must solve two problems: longevity (persistence) and efficiency (hashrate).

Scope of analysis

This report analyzes a specific infection cluster identified in late 2025. The primary artifacts include a deceptive installer, a legitimate but vulnerable driver, and a customized wrapper for the XMRig miner.

2. Infection vector and social engineering

The entry point for this campaign relies on a classic but highly effective social engineering tactic: the promise of free premium software. The distribution vector is identified as pirated software bundles, specifically masquerading as legitimate installers for office productivity suites.

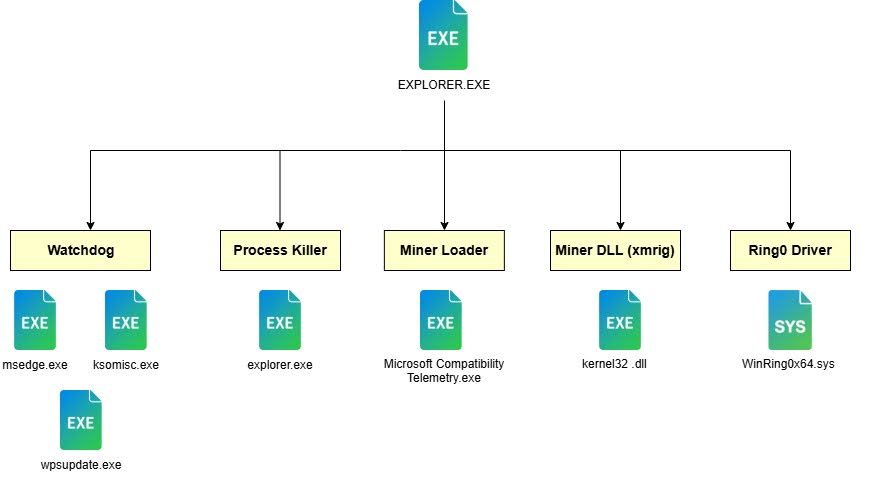

3. The "Explorer.exe" controller: Architecture and operational philosophy

The "Explorer.exe" binary [MD5: bb97dfc3e5fb8109bd154c2b2b2959da] functions as the primary orchestration node for the infection. In traditional malware design, functionality is often compartmentalized into a linear execution flow: a dropper downloads a payload, executes it, and exits. Explorer.exe (controller), however, operates as a persistent state machine. It determines its behavioral mode based on the specific command-line arguments passed to it during execution, allowing a single binary file to serve multiple distinct operational roles within the infection lifecycle: installer, watchdog, payload manager, and cleaner.

3.1 The "Brain" vs. "Brawn" separation

A key insight derived from the reverse engineering of the "Explorer.exe" is the deliberate architectural separation of command logic ("Brain") from execution logic ("Brawn"). This modular design principle enhances the stability and resilience of the infection.

- The Brain (Explorer.exe): This component handles logic, monitoring, timing, and decision-making. It is designed to be lightweight and stable. It does not perform the heavy computational lifting (mining) or the high-risk aggressive actions (process termination) directly. This minimizes the risk of the controller crashing or triggering behavioral heuristics in security software, ensuring the "manager" remains active even if the "workers" are neutralized.

- The Brawn (Payloads):

- Mining operations: Handled by “Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe”, a wrapper for the XMRig miner.

- Enforcement operations: Watchdogs

- Kernel access: Handled by WinRing0x64.sys, a vulnerable driver exploited to gain Ring 0 access.

3.2 The “Cultural Profiling”: Command line parameters and state control

The malware's internal logic is heavily laden with references to the anime series Re:Zero - Starting Life in Another World. The use of strings such as Re:0 and barusu suggests a specific psychological profile of the malware author.

These references are not mere superficial additions but are functionally integrated into the control flow. Specifically, the "002 Re:0" argument initiates the "Active Infection" mode. This is a direct parallel to the anime protagonist's "Return by Death" ability, a metaphor that perfectly illustrates the malware's persistence mechanism: much like the protagonist's resurrection, if the infection is terminated, its watchdog components ensure it "returns.”

The malware implements a form of "mode switching" via command-line arguments. This technique serves a dual purpose: it maximizes code reuse (allowing one binary to perform all necessary functions) and acts as a rudimentary anti-analysis mechanism.

The following table details the command line parameters decoded from the binary entry point logic, correlating specific parameters with their internal mode names and functional roles:

| Parameter | Internal mode name | Functional role | Trigger mechanism |

| (None) | Installation mode | Environment validation and migration. Checks if running from the correct path; if not, copies to the target and exits. | User double-click (Initial Infection via Dropper). |

| 002 Re:0 | Active infection | The "Master" mode. Drops payload files, starts the miner, and enters the main monitoring loop. | Self-triggered after successful installation and migration. |

| 016 | Maintenance | Health check mode. Scans for the miner process. If running, exit. If dead, restart it. | Triggered by watchdog processes (msedge.exe, ksomisc.exe). |

| barusu | Kill switch | Destruct sequence. Terminates all malware components and deletes files. | Triggered by the "Time Bomb" (Date Check) or manual cleanup routine. |

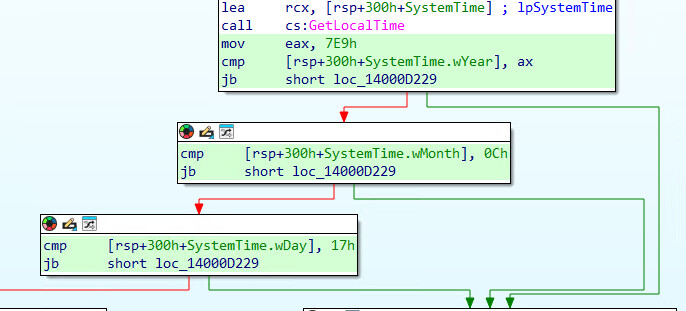

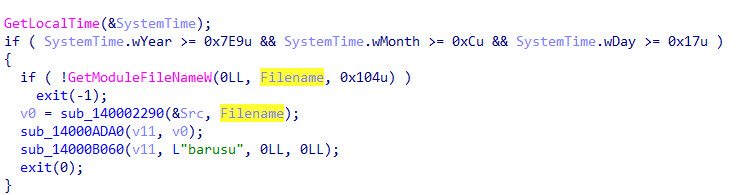

3.3 The "Time Bomb" logic: A campaign lifecycle

A significant discovery within the sub_14000D180 function is a hardcoded temporal check, serving as a "kill switch" or "time bomb." This mechanism operates by retrieving the local system time and comparing it against a predetermined deadline: December 23, 2025.

The malware's behavior diverges based on this date:

- Active phase (Pre-Dec 23, 2025): The malware proceeds with the standard infection routine, installing the persistence modules and launching the miner.

- Expiration phase (Post-Dec 23, 2025): This suggests that the campaign is not intended to be an indefinite operation. It implies a "fire-and-forget" lifecycle, possibly timed to coincide with the expiration of rented Command & Control (C2) infrastructure, a predicted shift in the cryptocurrency market (specifically Monero difficulty adjustments), or a planned transition to a new malware variant.

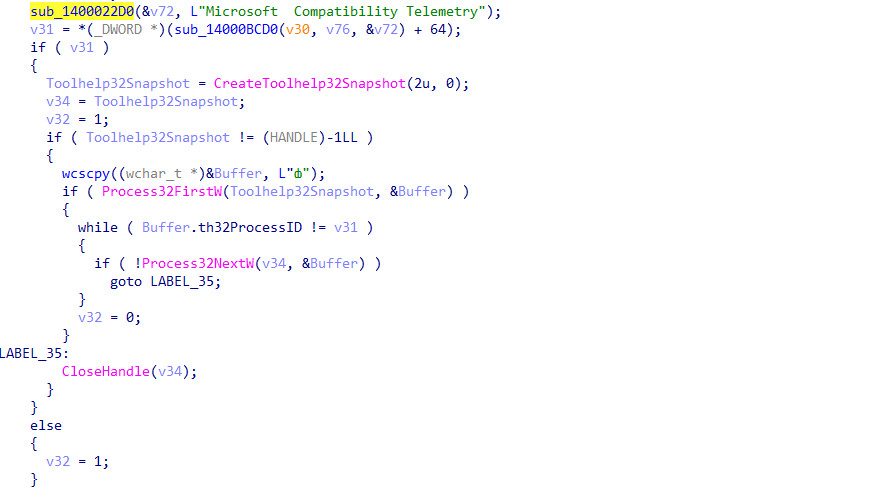

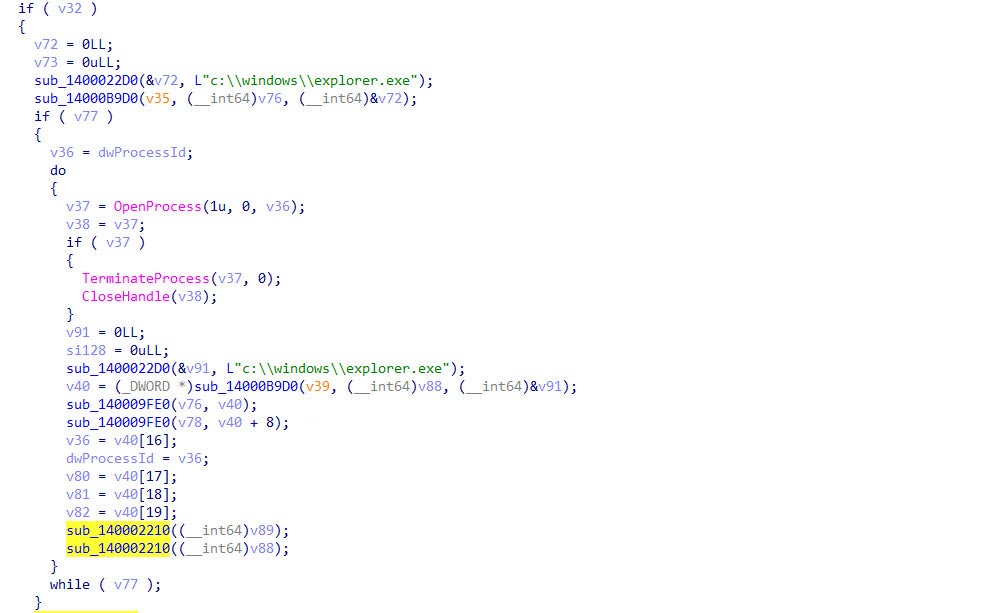

3.4 The "Barusu" protocol (cleanup routine)

When the binary is launched with the barusu argument triggered either by the Time Bomb or potentially by a manual command from the threat actor, it enters a comprehensive cleanup mode designed to wipe the infection from the host. This is not a chaotic self-destruct; it is a controlled decommissioning of the infection.

The Cleanup sequence:

- Snapshot & hunt: It calls the Process Scanner (sub_14000B700) to generate a dynamic list of all running processes on the host.

- Targeted termination: It iterates through the list, looking for specific operational components of the malware:

- Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe (The Miner)

- explorer.exe (The Process killer)

- msedge.exe (Persistence Watchdog 1)

- ksomisc.exe (Persistence Watchdog 2)

- Wpsupdate.exe (Persistence Watchdog 3)

- Process killing: It terminates these processes using the TerminateProcess API to release their file locks.

- File wipe: Once the processes are dead, it calls the DeleteFileW API on the dropped payloads, removing the WPS, Microsoft Edge, and root explorer.exe files it created.

3.5 Path enforcement logic

Upon execution without arguments (the standard behavior when a user double-clicks a downloaded file), Explorer.exe calls the Windows API GetModuleFileNameW to retrieve its current full path on the disk. It then compares this string against a hardcoded target path:

C:\Users\%USERNAME%\explorer.exe

This comparison creates a critical fork in the execution flow:

- The Match Condition (Already Installed): If the current path matches the target path, the malware assumes it is successfully installed in the correct location. It then re-launches itself with the argument 002 Re:0 to begin the active infection phase.

- The Mismatch Condition (New Infection): If the path does not match (e.g., the user ran the installer explorer.exe from C:\Users\User\Downloads\ or C:\Users\User\Desktop\), the malware assumes it is in the setup phase.

- It identifies the target destination: C:\Users\%USERNAME%\explorer.exe

- It copies itself to this target path using CopyFileW.

- It executes the new copy (which will now find a path match).

- Crucially, it immediately calls exit(0) to terminate the original process running in the Downloads folder.

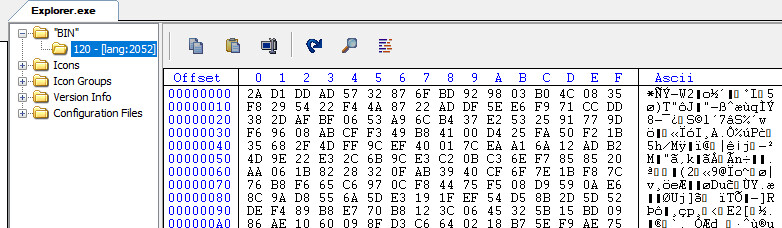

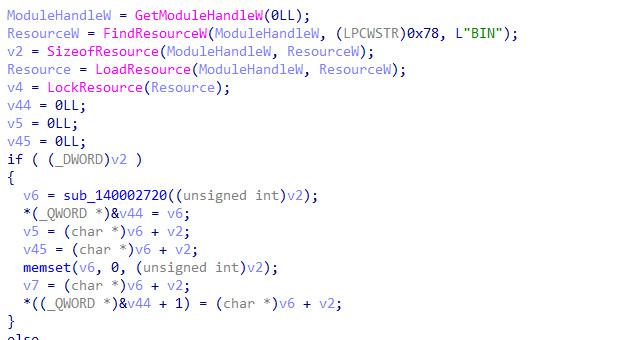

3.6 Resource management and payload extraction

Explorer.exe acts as a self-contained carrier for the entire infection suite. It does not rely on downloading payloads from a remote C2 server.

The resource section and decompression

The payload is stored within the binary PE Resource Section under the ID BIN (Resource ID 120). The malware uses the standard Windows APIs FindResourceW, LoadResource, and LockResource to access this data blob in memory.

The loaded resource is a compressed archive. Function sub_14000AA20 decompresses this blob.

The file inventory

Once decompressed, the data blob is split into seven distinct files, which are written to disk. The file inventory reveals the malware's multi-layered strategy of deception and persistence:

| Filename | Role | Masquerade / technique |

| Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe | Miner Wrapper | Mimics the legitimate Windows Telemetry service (CompatTelRunner.exe). Loads the mining DLL. Typosquatting (missing 'i' in Compatibility). |

| Kernel32 .dll | XMRig DLL | The actual mining code is compiled as a DLL. Uses the "Space" trick to look like a system DLL (kernel32.dll). |

| explorer .exe | Ghost Enforcer | A killer process used to terminate security tools. Uses the "Space" trick. |

| WPS\wps.exe | Decoy and Persistence Keeper | Mimics WPS Office software to justify the folder presence to the user. |

| ksomisc.exe | Persistence Keeper | Watchdog process |

| Microsoft Edge\edge.exe | Persistence Keeper | Watchdog process |

| winRing0x64.sys | Exploit Driver | Legitimate but vulnerable driver (CVE-2020-14979) used for BYOVD exploitation. |

Immediately after writing these files to disk, Explorer.exe calls SetFileAttributesW to apply FILE_ATTRIBUTE_HIDDEN | FILE_ATTRIBUTE_SYSTEM. This renders the files invisible to the user unless the "Show hidden files" and "Show protected operating system files" options are explicitly enabled in Windows Folder Options.

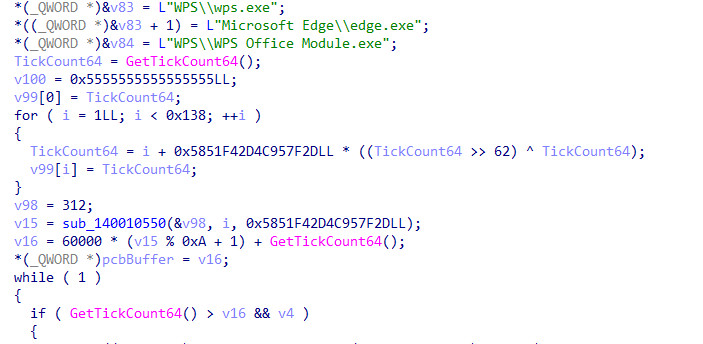

3.7 The main orchestration loop

Once the payload is dropped and the environment is mapped, Explorer.exe (running in 002 Re:0 mode) enters its main orchestration loop (sub_14000D330). This is an infinite loop that serves as the heartbeat of the infection, maintaining the state of the botnet node.

The function starts with while ( 1 ) infinite loop and does all the work, then sleeps for 200ms

Circular dependency: The self-healing watchdog topology

The campaign employs a redundant, circular persistence model reminiscent of the mythical Hydra—cut off one head, and another takes its place. This is achieved through the interaction between Explorer.exe and its "Keepers" (Watchdogs).

The loop uses GetTickCount64 (which retrieves the number of milliseconds since the system started) to seed a custom random number generator. Based on this timer, the malware randomly launches one of its Keepers:

- C:\Users\%USERNAME%\Microsoft Edge\edge.exe

- C:\Users\%USERNAME%\WPS\WPS Office Module.exe

- C:\Users\%USERNAME%\WPS\wps.exe

These Keepers are not independent programs; they are clones or specific variants of the controller designed to execute the command immediately:

explorer.exe 016

This command points back to the main Explorer.exe binary. This creates a self-reinforcing loop:

- Scenario A (main crash): If Explorer.exe crashes or is terminated, the next scheduled run of edge.exe (Keeper) will execute explorer.exe 016, which checks the miner and restarts the main logic if necessary.

- Scenario B (keeper death): If the user deletes or kills edge.exe, Explorer.exe (which is running independently in its loop) will simply re-launch or re-drop it during its next loop iteration.

This "Circular Watchdog" topology makes the malware extremely annoying to remove. A user must terminate all components almost simultaneously to stop the cycle; otherwise, the surviving components essentially "resurrect" the dead ones within seconds.

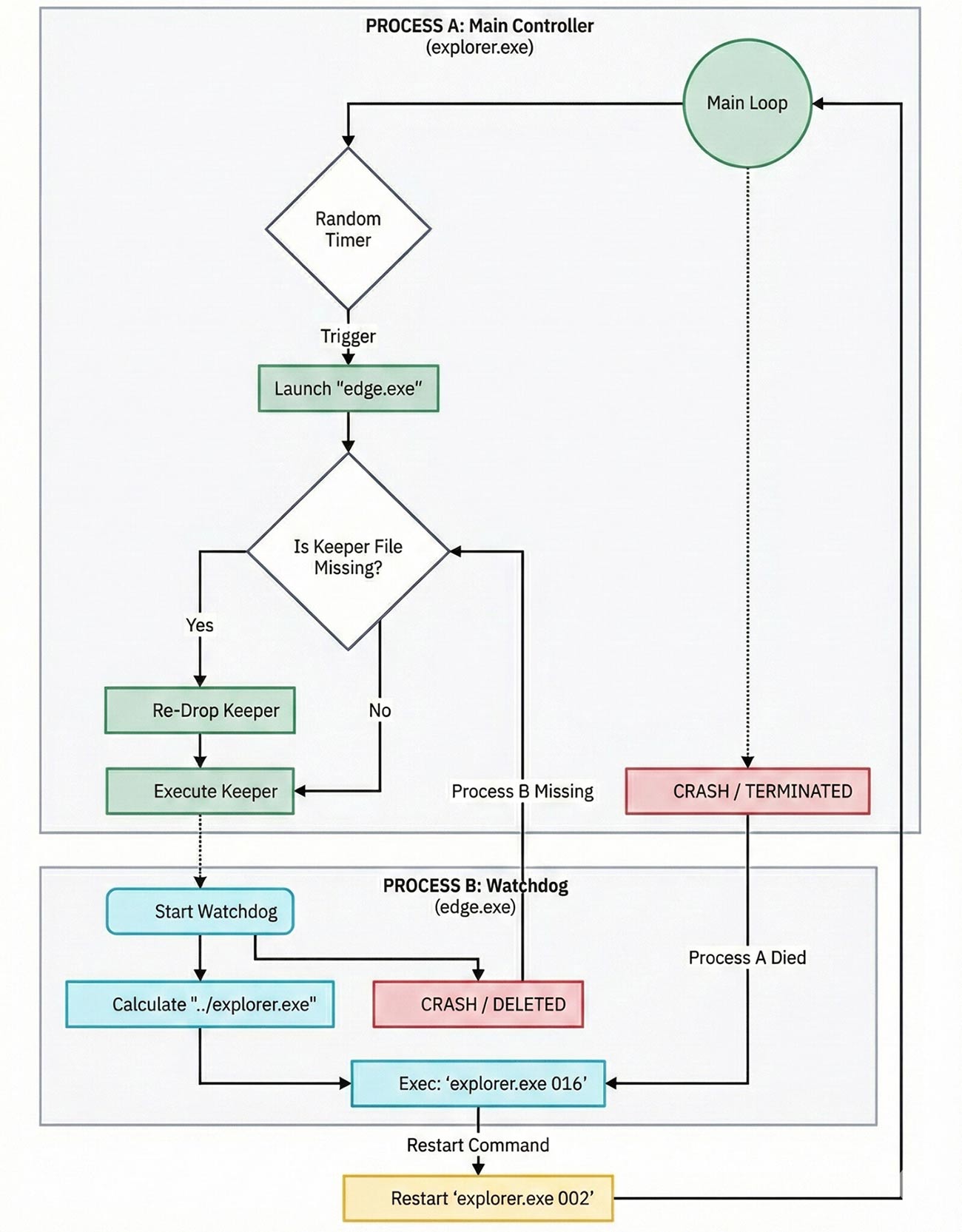

System surveillance

The malware utilizes the Process32First and Process32Next functions to traverse this process snapshot. However, identifying a target based solely on its process name, such as explorer.exe, is often inadequate for advanced malware due to potential name ambiguity. Consequently, Explorer.exe employs an additional, more sophisticated method:

- It obtains a handle to each process using OpenProcess with specific access rights (likely PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION or PROCESS_VM_READ).

- It uses K32GetModuleFileNameExW to resolve the Full Filesystem Path of the executable image.

This path resolution is critical for three operational objectives:

- Self-identification: It must distinguish between its own components (C:\Users\User\explorer.exe) and the system's legitimate shell (C:\Windows\explorer.exe).

- Health monitoring: It scans specifically for Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe (the miner) to ensure it is running. If the process is missing from the snapshot, the controller knows to restart it.

The miner watchdog and aggressive defense

The loop constantly queries the status of the miner process (Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe).

- Restart Logic: If the miner process is missing from the snapshot or returns an exit code indicating failure, Explorer.exe relaunches it immediately.

- The "Nuclear" option: Analysis reveals a specific aggressive defense mechanism. If the miner fails to start repeatedly or encounters specific error states (possibly indicating a file lock or antivirus interference), Explorer.exe attempts to call TerminateProcess on the Real Windows Explorer (C:\Windows\explorer.exe).

Killing the system's explorer.exe causes the Windows taskbar, start menu, and desktop icons to disappear. This effectively "blinds" the user, creating panic and often forcing a soft reboot of the user session. This chaos provides cover for the malware to attempt a re-injection during the shell restart sequence, effectively resetting the board in its favor.

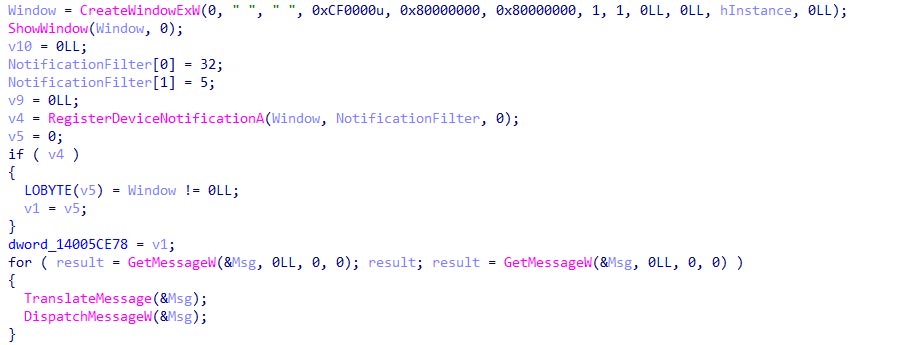

3.8. Lateral propagation: The worm module

A distinguishing feature of this XMRig variant is its aggressive propagation capability. It does not rely solely on the user downloading the dropper; it actively attempts to spread to other systems via removable media. This transforms the malware from a simple trojan into a worm.

The WM_DEVICECHANGE listener

The functions sub_1400132E0 and sub_14000E090 contain the logic for the worm module. It creates a Hidden Window (Class Name " ") using CreateWindowExW with SW_HIDE. Instead of polling the system for new drives (which consumes CPU and generates detectable I/O noise), the malware registers a passive listener using the Windows API RegisterDeviceNotificationA.

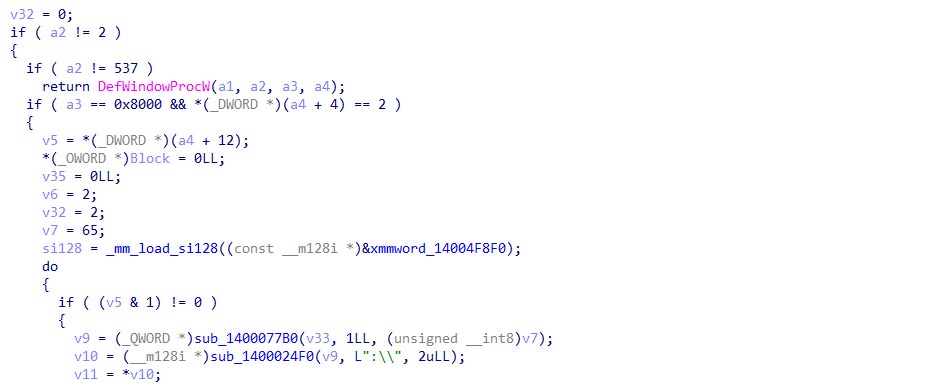

It configures a DEV_BROADCAST_DEVICEINTERFACE filter to listen for the WM_DEVICECHANGE (0x219) message. Specifically, it waits for the DBT_DEVICEARRIVAL (0x8000) event code, which the Windows kernel broadcasts to all top-level windows when a device is inserted.

Propagation logic

When a device insertion event is detected, the malware inspects the dbcv_devicetype. It specifically looks for type 2 (DBT_DEVTYP_VOLUME), which corresponds to logical storage volumes like USB flash drives or external hard disks.

| Code Artifact | Meaning |

| WM_DEVICECHANGE (537) | Watching for hardware changes. |

| DBT_DEVICEARRIVAL (0x8000) | Something was just plugged in. |

| DBT_DEVTYP_VOLUME (2) | It is a storage device (USB/HDD). |

| v7 = 65 ... 90 | iterates through drive letters (E:, F:, G:) to identify the new volume. |

| sub_140014190 | copies the explorer.exe binary to the drive and creates a hidden folder for the payload. |

The infection routine typically involves copying the explorer.exe binary to the USB drive, creating a hidden folder for the payload, and creating an LNK (shortcut) exploit (masquerading as the drive icon) to trick the user into executing the malware when they open the USB drive on a different computer.

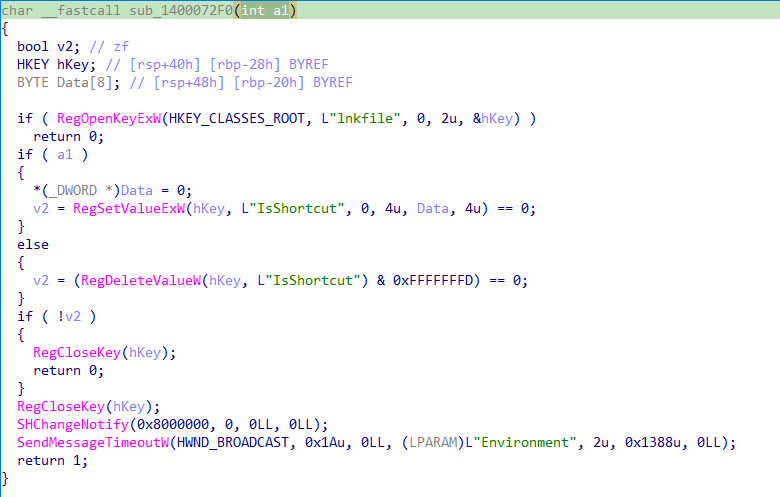

3.9. UI spoofing - Icon tamperer via registry manipulation. (sub_1400072F0)

This function is a specific "Stealth Toggle" designed to manipulate the visual appearance of files in Windows Explorer. Its goal is to make malicious Shortcut (.lnk) files look indistinguishable from legitimate Executables or Documents by removing the small curved arrow overlay in the bottom-left corner of its icon.

The toggle logic

The code branches based on the input a1 show as in Table 4

| Input (a1) | Action | Registry Operation | Visual Result |

| 0 | Hide Arrow | RegDeleteValueW "IsShortcut" | Clean icon (no overlay) |

| 1 | Show Arrow | RegSetValueExW "IsShortcut" | Default icon (with arrow) |

When is it called

The cross-references (WinMain+156 and WinMain+84F) indicate it is used at specific lifecycle stages.

- Infection phase (WinMain+156): Called with 0 (Hide). This prepares the environment before the malware creates any malicious shortcuts on the drives (via the Worm module). It ensures the user won't see the "Shortcut Arrow" warning sign on newly infected files.

- The "Cleanup" phase (WinMain+84F): Called with 1 (Restore). After the malicious payload executes, the code attempts to cover its tracks, followed by the File Deletion Loop calling the DeleteFileW API repeatedly to leave no evidence.

4. The watchdogs: Strategic redundancy

To ensure the malware survives attempts at removal, the attacker drops three distinct executables in subfolders masquerading as legitimate software:

- C:\Users\%USERNAME%\Microsoft Edge\edge.exe [SHA256: 705e3be6bab0b0773e89de02dc53e4947db65a41d93cfe2b592b43fd3d2f4f74]

- C:\Users\%USERNAME%\WPS\wps.exe (or wpsupdate.exe) [SHA256: 69c8c640f35d3f23f8e2997770833f99652a36c5c9c6f6354b021ba3eab93257]

- C:\Users\%USERNAME%\WPS\ksomisc.exe [SHA256: ebdfb99d7125311dfa8261bb7a98e2e415d15d67369f923f31fb27e36d446ec9]

Upon recovering these samples, we performed a binary differentiation (BinDiff) analysis to compare their internal logic and found they are functionally identical. Despite having different filenames and icons to match their disguise, the compiled code, entry point logic (sub_140001410), and string structures are exact matches. The attacker compiled a single "Trigger" payload and renamed it multiple times to create a redundant safety net. If a user deletes the fake "Edge" browser, the fake "WPS" update remains to sustain the infection.

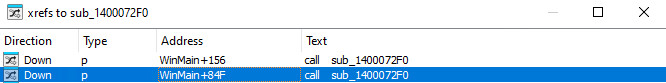

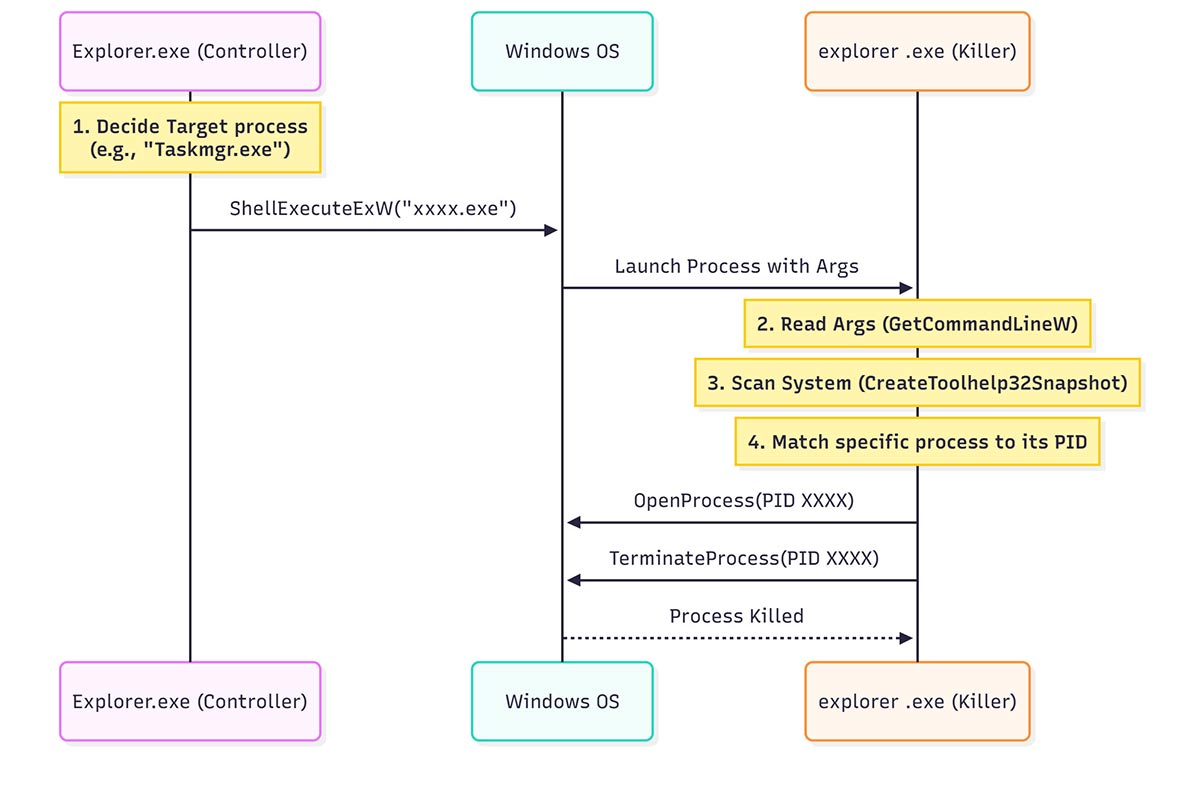

5. The ghost enforcer: explorer .exe

The Explorer.exe acts as the Main Controller and persistence engine, managing the infection lifecycle and monitoring system health. It spawns explorer .exe [SHA256: 51b98f8fb38e822245a1b22864652d7d091dd2f52424786051cbc8131b7e782b], which functions as a transient Process Killer designed to terminate processes.

The handshake happens via ShellExecuteExW and passing a list of target process names as command-line arguments. Explorer .exe(killer) then resolves these names to PIDs, terminates them, and immediately exits, operating on a "fire-and-forget" basis.

6. Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe - The payload wrapper

The ultimate goal of the campaign is to run the XMRig miner. However, running the standard xmrig.exe is a guaranteed way to trigger antivirus detection. To avoid this, the attackers employ a sophisticated wrapping and sideloading technique.

6.1 The Microsoft telemetry App masquerade

The mining process is named Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe. [SHA256:5936ae20028b79e3ebb58f863960e56f93aed4e7a07f0b39a80205a8a7df5579]

- Typosquatting: Note the missing 'i' in "Compatbility". The legitimate Windows binary is CompatTelRunner.exe, often described in Task Manager as "Microsoft Compatibility Telemetry".

- Visual camouflage: By adopting a name that is visually similar to a known, high-noise Windows system process, the malware hopes to blend in. Users are accustomed to seeing "Telemetry" processes consuming resources, so they may overlook the miner's activity.

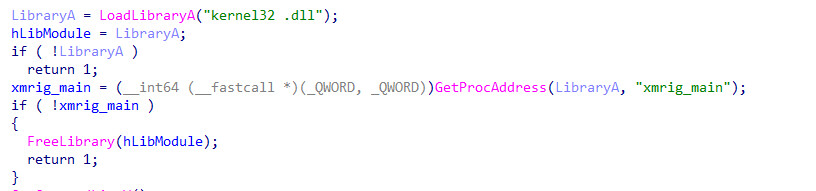

6.2 DLL sideloading and the "Kernel32" trick

The executable Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe does not contain the mining code itself. It is a "dumb" loader. Analysis reveals it uses DLL Sideloading to load the actual payload.

Here, the "Space Trick" appears again. The malware attempts to load a DLL named kernel32 .dll (with a space).

This fake DLL is actually the XMRig miner compiled as a dynamic library. The loader then calls GetProcAddress to find the exported function xmrig_main.

6.3 Argument parsing and execution

The wrapper acts as a translator. It takes the arguments passed to the EXE (e.g., --coin XMR --url xmr-sg.kryptex.net) and converts them into the format expected by the XMRig DLL. This decoupling of the loader and the miner allows the attackers to easily swap out the mining DLL (e.g., updating the XMRig version) without changing the persistent loader executable.

7. Deep dive: Kernel mode exploitation (BYOVD)

The most technically sophisticated component of this malware is its use of the Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver (BYOVD) technique. This allows the user-mode miner to execute code with Kernel (Ring 0) privileges, bypassing the operating system's hardware abstraction layer.

7.1 The target: WinRing0x64.sys

The malware drops a driver file named WinRing0x64.sys. This is a legitimate driver component of the "OpenLibSys" library, historically used by hardware monitoring tools (like Core Temp or MSI Afterburner) to read CPU temperatures and fan speeds.

However, version 1.2.0 of this driver contains a critical vulnerability, assigned CVE-2020-14979.

In its DriverEntry routine, the driver creates a device object (\Device\WinRing0_1_2_0) but fails to apply a restrictive Security Descriptor (SDDL). It creates the device with a NULL DACL (Discretionary Access Control List).

This means any user on the system, regardless of privilege level, can open a handle to this driver and send it commands. Since the driver is designed to read/write specific CPU registers, this effectively gives any user full control over the CPU's low-level configuration.

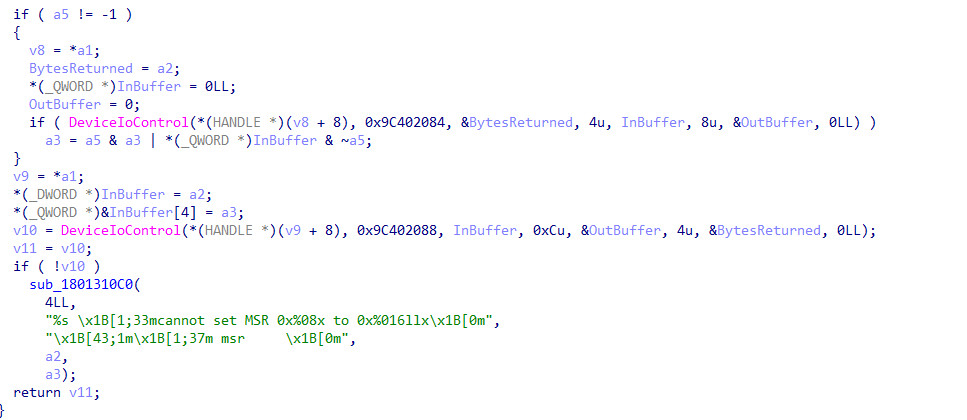

7.2 The exploit chain

The integration of this exploit into the XMRig payload is visible in the function sub_1802981C0 within the malicious DLL.

- Service creation: The malware calls CreateServiceW with the argument SERVICE_KERNEL_DRIVER (0x1). It points the service to the dropped WinRing0x64.sys file.

- Driver loading: It calls StartServiceW, forcing the Windows kernel to load the vulnerable driver.

- Communication channel: It calls CreateFileW(L"\\\\.\\WinRing0_1_2_0",...) to open a handle to the driver. Due to the CVE-2020-14979 this succeeds.

- IOCTL transmission: The miner uses DeviceIoControl to send specific Input/Output Control (IOCTL) codes to the driver.

7.3 MSR modification and hashrate boosting

The ultimate goal of this kernel excursion is to modify the Model Specific Registers (MSRs) of the CPU.

The RandomX mining algorithm used by Monero is designed to be "ASIC-resistant" and CPU-friendly. It relies heavily on random access to the CPU's cache memory. Modern CPUs have features called Hardware Prefetchers. These components predict what data the CPU will need next and fetch it from RAM into the L2/L3 cache.

- The Problem: For standard programs (linear access), prefetchers are great. For RandomX (random access), prefetchers are detrimental. They fill the valuable cache with predicted data that is never used, evicting the actual mining data and causing "cache thrashing."

- The Solution (The Exploit): The malware sends the IOCTL code 0x9C402088 (Write MSR) to the driver. The data packet contains the instruction to write to the MSR_PREFETCH_CONTROL register (Address 0x1A4 on Intel CPUs).

- The Result: The command disables the "L2 Hardware Prefetcher" and "L2 Adjacent Cache Line Prefetcher." Tests indicate this optimization increases the RandomX hashrate by 15% to 50%.

By utilizing BYOVD, the malware achieves this optimization without needing to write its own malicious driver (which would require a valid digital signature to load on modern Windows). It simply piggybacks on the valid signature of the old, vulnerable WinRing0 driver.

8. Threat intelligence and attribution

8.1 Infrastructure and monetization

The campaign utilizes the Kryptex mining pool (xmr-sg.kryptex.net).

- Mining pool: The campaign utilizes xmr-sg.kryptex.network:8029. Kryptex is a consumer-grade mining platform that pays out in fiat or Bitcoin, popular among entry-level cybercriminals for its ease of laundering.

- Wallet: 42DKy5tDGH5MjwWDw2nAj7ZydTsX43cxM5T7zfjPezaEav51eALbqQhDo6ZUgF58tA3s28LnvSTUKTdAZUtqcGXsTBZrDfH. This is a standard Monero address. Due to Monero's ring signatures and stealth addresses, the balance and transaction history are opaque, making the proceeds untraceable.

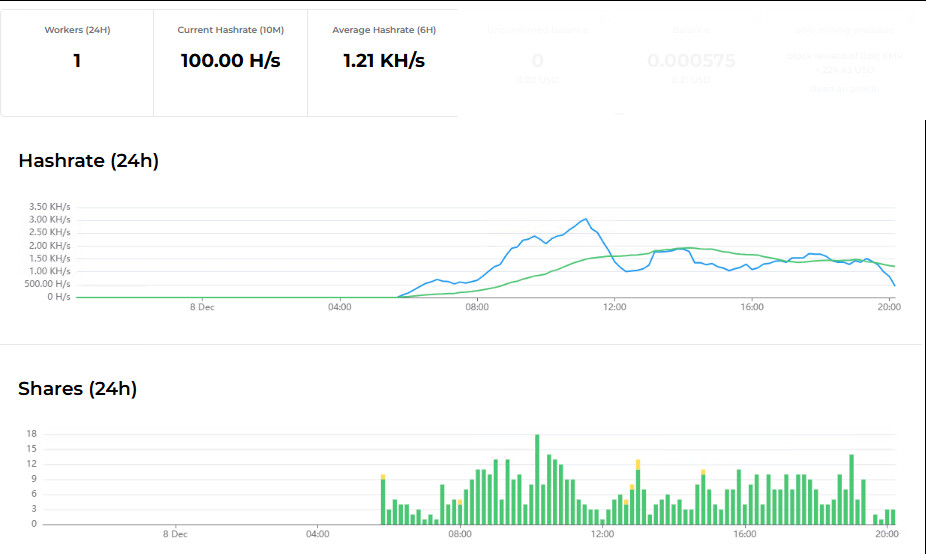

8.2 Campaign status

The threat actor is currently testing the infection chain and persistence mechanisms (like the "Barusu" kill switch) on a small number of machines before a wider distribution. The pool reports 1 active worker (identified as "a") with a 24-hour average hashrate of approximately 1.24 KH/s.

Historical data shows sporadic mining activity throughout November 2025, with a distinct spike in activity beginning on December 8, 2025. This correlates with the analysis timeline, suggesting either a fresh deployment of the campaign or the activation of new nodes.

9. Conclusion

This campaign serves as a potent reminder that commodity malware continues to innovate. By chaining together social engineering, legitimate software masquerades, worm-like propagation, and kernel-level exploitation, the attackers have created a resilient and highly efficient botnet. The use of the BYOVD technique, in particular, highlights a critical weakness in modern OS security models: the trust placed in signed drivers. As long as legacy drivers with known vulnerabilities remain validly signed and loadable, attackers will continue to use them as keys to the kingdom, bypassing the sophisticated protections of Ring 3 to operate with impunity in the Kernel.

10. Trellix protection and mitigation

Trellix has implemented comprehensive protection and mitigation measures against this cryptojacking campaign and its associated components. Our security solutions include coverage for all known executables, including the malicious controller, the XMRig payload wrapper, and the BYOVD exploit chain. This proactive approach aims to safeguard our customers by detecting the infection at the dropper stage and neutralizing the persistence mechanisms.

11. CISO recommendations: Strengthening defense with Trellix

For security leaders, this campaign underscores the evolving sophistication of commodity malware, particularly in its use of kernel-level exploitation. Trellix customers are currently protected against this threat: our Endpoint Security (ENS), EDR, and Network Security solutions successfully detect and block the associated malicious executables, payloads, and network behaviors.

To further strengthen your organization's resilience against similar future threats, we recommend the following strategic actions:

- Neutralize the "BYOVD" Vector: While Trellix protects against the malware payload, the root vulnerability lies in signed, legacy drivers. We strongly advise organizations to enforce Microsoft’s Vulnerable Driver Blocklist (via Windows Defender Application Control or HVCI). This prevents known-vulnerable drivers, such as the WinRing0x64.sys used in this campaign, from ever loading into the kernel.

- Leverage ENS device control: The "worm" component of this campaign relies on physical propagation via USB drives. Ensure your Trellix ENS policies include Device Control measures to automatically scan or restrict removable media, cutting off this lateral movement vector.

- Unify network & endpoint defense: Capitalize on Trellix Endpoint Security Web Control to block outbound connections to consumer-grade mining pools. Administrators should configure the Block and Allow List policy to explicitly deny access to known mining domains (e.g., xmr-sg.kryptex.network) and enforce Web Category Blocking for high-risk categories. This ensures that even if an infected device enters your network, it cannot monetize hijacked resources.

- Address the human element: Since the infection vector is socially engineered pirated software, reinforce security awareness training regarding software sourcing.

Appendix A - Indicators of compromise

| SHA256 / Data | Description |

| 6bd854762e13e9099752ee67b89f841403167358616110033805fc3f218e4d46 | EXPLORER.EXE |

| 11bd2c9f9e2397c9a16e0990e4ed2cf0679498fe0fd418a3dfdac60b5c160ee5 | WinRing0.sys |

| 51b98f8fb38e822245a1b22864652d7d091dd2f52424786051cbc8131b7e782b | explorer .exe |

5936ae20028b79e3ebb58f863960e56f93aed4e7a07f0b39a80205a8a7df5579 |

Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe |

| 69c8c640f35d3f23f8e2997770833f99652a36c5c9c6f6354b021ba3eab93257 | wpsupdate.exe |

| 705e3be6bab0b0773e89de02dc53e4947db65a41d93cfe2b592b43fd3d2f4f74 | msedge.exe |

| bd731032cd5f051724ca56e6bb18c64e51c9b442a80a80e6642a92d3cfbaa4df | Kernel32 .dll |

| ebdfb99d7125311dfa8261bb7a98e2e415d15d67369f923f31fb27e36d446ec9 | ksomisc.exe |

| 42DKy5tDGH5MjwWDw2nAj7ZydTsX43cxM5T7zfjPezaEav51eALbqQhDo6ZUgF58tA3s28LnvSTUKTdAZUtqcGXsTBZrDfH | Wallet ID |

| xmr-sg.kryptex.network:8029 | URL |

Appendix B - Trellix detection signatures

| Product | Signature |

| Trellix Endpoint Security (ENS) | Trojan-FZTA Trojan-FZPB Trojan-FZPE Trojan-FZPC Trojan-FZPF Trojan-FZPG Trojan-FZPA |

| Trellix VX Trellix Cloud | FE_Tool_Win_XMrig_5 FE_Trojan_Win_Generic_444 FE_Trojan_Win_Generic_445 FE_Trojan_Win_Generic_446 FE_Trojan_Win_Generic_447 FE_Loader_Win_Generic_182 |

| Trellix Network Security MVX Trellix File Protect Trellix Malware Analysis Trellix SmartVision Trellix Detection As A Service Trellix NX | Tool.CoinMiner (86117227) Tool.CoinMiner (86119921) Trojan.CoinMiner (86122917) Tool.Win.XMRig.MVX (21892) Suspicious File Activity (10081) Suspicious File Dropper Activity (10048) Suspicious Process Hijacking Activity (10073) Suspicious File Manipulation On Known Benign Filenames (10179) Suspicious Registry on File Dropped (10247) Suspicious File Self Copy and Persistence (10760) Riskware Network Activity with cnc Backdoor behavior (50024) |

Appendix C - MITRE ATT&CK

| Tactical Goal | ATT&CK Technique (Technique ID) | Description |

| Initial Access | T1204.002 User Execution: Malicious File | User downloads and double-clicks the "Office Crack" or utility installer file. |

| Execution | T1059.003 Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell |

The watchdogs (msedge.exe, wpsupdate.exe, and ksomisc.exe) execute the controller using shell commands with arguments (e.g., explorer.exe 016). |

| Persistence | T1543.003 Create or Modify System Process: Windows Service |

The miner loader creates a kernel-mode driver service named WinRing0_1_2_0 to load the vulnerable WinRing0x64.sys driver. |

| T1574.002 Hijack Execution Flow: DLL Side-Loading | Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe (Wrapper) loads a malicious DLL named kernel32 .dll from the local directory instead of the system library. | |

| T1546 Event Triggered Execution: Trap | The persistence mechanism relies on a circular "Hydra" loop where Watchdogs (msedge, wpsupdate, ksomisc.exe) constantly re-trigger the main controller explorer.exe. | |

| Privilege Escalation | T1134 Access Token Manipulation | The malware requests SeDebugPrivilege or uses the vulnerable driver to manipulate process tokens (implied by kernel-level access). |

| T1068 Exploitation for Privilege Escalation |

The miner uses the "Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver" (BYOVD) technique, exploiting CVE-2020-14979 in WinRing0x64.sys to gain Ring 0 (Kernel) access. | |

| Defense Evasion | T1036.003 Masquerading: Rename System Utilities | The malware names its components explorer.exe (User Profile), Microsoft Compatbility Telemetry.exe, and msedge.exe to look like legitimate Windows binaries. |

| T1036.006 Masquerading: Space after Filename | It uses kernel32 .dll and explorer .exe (Space Trick) to visually deceive users and potentially bypass exact-match string filters. | |

| T1564.001 Hide Artifacts: Hidden Files and Directories | The dropper immediately sets FILE_ATTRIBUTE_HIDDEN and SYSTEM on all dropped payloads (WPS folder, WinRing0, etc.). | |

| T1112 Modify Registry | Modifies HKCR\lnkfile\IsShortcut to hide the shortcut arrow overlay, making malicious LNK files look like legitimate EXEs or documents. | |

| T1070.004 File Deletion | The "Barusu" kill switch (Time Bomb) triggers a cleanup routine that deletes the dropped files to remove forensic evidence. | |

| Discovery | T1057 Process Discovery | Uses CreateToolhelp32Snapshot to list running processes, identifying targets to kill or to check their own health. |

| T1124 System Time Discovery | Checks GetLocalTime to trigger the "Time Bomb" logic (Kill switch after Dec 23, 2025). | |

| T1120 Peripheral Device Discovery | Scans for Removable Drives (GetDriveTypeA == 2) to identify targets for the worm module. | |

| Impact | T1496 Resource Hijacking | The primary goal: Using the victim's CPU to mine Monero (XMR) via the XMRig payload. |

| T1489 Service Stop | The "Killer" module (explorer .exe) aggressively terminates legitimate explorer.exe |

Discover the latest cybersecurity research from the Trellix Advanced Research Center: https://www.trellix.com/advanced-research-center/

RECENT NEWS

-

Mar 02, 2026

Trellix strengthens executive leadership team to accelerate cyber resilience vision

-

Feb 10, 2026

Trellix SecondSight actionable threat hunting strengthens cyber resilience

-

Dec 16, 2025

Trellix NDR Strengthens OT-IT Security Convergence

-

Dec 11, 2025

Trellix Finds 97% of CISOs Agree Hybrid Infrastructure Provides Greater Resilience

-

Oct 29, 2025

Trellix Announces No-Code Security Workflows for Faster Investigation and Response

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.