Cyber Readiness in Asia Pacific Region: Australia, India & Japan

By Trellix · April 14, 2022

Countries such as India, Australia and Japan are facing increasingly sophisticated attacks on government agencies and organizations providing critical infrastructure services:

- October 2020 – A border skirmish between China’s People’s Liberation Army and the Indian Armed Forces in the Himalayas was followed up by a cyber-attack on Mumbai’s power grid control systems, shutting down trains, closing the stock market, blacking out pandemic-besieged hospitals and cutting power for 20 million people.

- October 2019 – October 2020 – A software supply chain cyber-attack launched through Fujitsu’s ProjectWeb tool to compromise Japanese government and critical infrastructure networks, exfiltrating sensitive information on Japan’s air transportation operations and travel schedules.

- November 2021 – Almost 3 million Australian homes lost power when a major energy network was hit by a cyber-attack, reinforcing the Department of Home Affairs 2020 report that around 35% of cyber-attacks hitting the nation "impact critical infrastructure providers that deliver essential services including healthcare, education, banking, water, communications, transport and energy.”

The incidents, among many others, are reminders that government agencies and critical infrastructure enterprises must improve their cyber defenses through a combination of the implementation of advanced cyber security technologies, enhanced policies and practices, and strengthened partnerships with their governments.

This blog focuses on the Asia Pacific results of a survey commissioned by Trellix and conducted by Vanson Bourne in late 2021 for the Trellix Cyber Readiness Report. Two hundred IT security professionals from government agencies and critical infrastructure providers with 500 or more employees were surveyed in India, Australia and Japan.

The government survey subjects included a mix of national and regional agencies. Critical infrastructure providers (CIPs) included traditional utilities providing electricity, water, oil and gas providers. They also included telecommunications and network service providers (traditional phone, IT network and internet services, broadcast services, etc.), public and private healthcare providers (hospitals, medical clinics, urgent care centers, etc.), transportation and distribution providers, state and local government service providers (including first responders and emergency services), and manufacturers of transportation, healthcare (pharmaceutical, etc.) and chemical products.

What emerges is a snapshot into the state of software supply chain risk and challenges, barriers to implementation of new solutions, the impact and legacy of COVID-19 on cybersecurity, and the current and potential role of government in cybersecurity.

Barriers to New Cyber Defenses

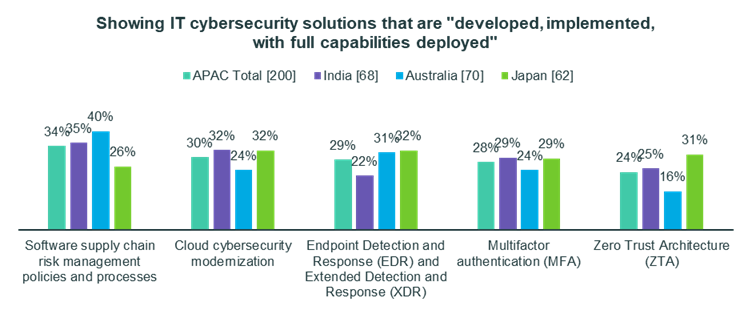

Maturity of Advanced Cyber Defenses. The survey gauged the priorities, difficulties and progress of their implementations of new cyber defense technologies such as cloud cybersecurity modernization, endpoint detection and response and extended detection and response (EDR-XDR), multifactor authentication (MFA) and zero trust architecture (ZTA).

Thirty-two percent of Indian respondents claim to have fully implemented cloud cybersecurity modernization and 29% appear to have fully implemented multifactor authentication (MFA). The cyber defense technologies lagging furthest behind in India appear to be zero trust architectures (25% at full deployment) and EDR-XDR (22% at full deployment).

Thirty-one percent of Australian respondents reported fully deploying EDR-XDR solutions. The advanced technologies lagging furthest behind were cloud cybersecurity modernization (24%), MFA (24%) and ZTA (16%).

Among Japanese respondents, EDR-XDR and cloud cybersecurity modernization were the most mature, with 32% of respondent claiming full deployment. Zero trust was close behind with 31% claiming full deployment, and MFA appears to be furthest behind at 29%.

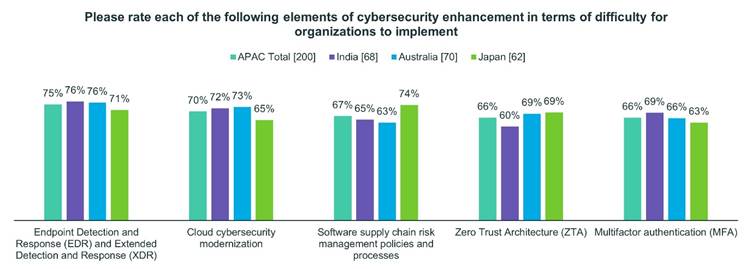

Among Indian and Australian respondents, EDR-XDR solutions appear to be the most difficult for organizations to implement. Seventy-six percent of Indian respondents identified EDR-XDR as either extremely or highly difficult to implement, followed by cloud cybersecurity modernization (72%), MFA (69%) and ZTA (60%).

Seventy-six percent of Australian respondents identified EDR-XDR as extremely or highly difficult to implement, followed by Cloud Cybersecurity Modernization (73%), ZTA (69%) and MFA (66%).

Seventy-one percent of Japanese respondents identified EDR-XDR solutions as an extremely or highly difficult cybersecurity measure to implement, followed by Zero Trust (69%), Cloud Cybersecurity Modernization (65%) and MFA (63%).

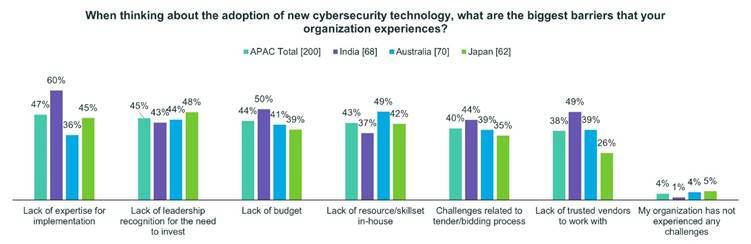

Sixty percent of Indian respondents identified a lack of implementation expertise as one of the biggest barriers to implementation of new cybersecurity solutions. Forty-nine percent of Australian respondents identified a lack of in-house staff resources as one of the biggest barriers to implementation of new cybersecurity solutions. Japanese respondents identified a lack of implementation expertise and leadership’s lack of recognition for the need to invest as among their top barriers to implementation of new cybersecurity solutions.

Software Supply Chain Risk

The aforementioned Fujitsu Project Web cyber-attack was one stark example of the kinds of software supply chain attacks that ravaged the Asia Pacific region over the last couple years. The software supply chain attacks on SolarWinds and Microsoft focused global attention on the seriousness of software supply chain cyber threats and how complicated it is to protect against them. They also realize that their governments can play a significant role in improving their cyber defenses.

Seventy-four percent of Japanese respondents identified software supply chain risk management policies and processes as a cybersecurity measure that is extremely or highly difficult to implement, and only 26% claim to have fully implemented such solutions.

Sixty-five percent of Indian respondents and 63% of Australian respondents identified these policies and processes as difficult to implement. Only 35% of Indian respondents and 40% of Australian respondents acknowledge fully implementing such measures.

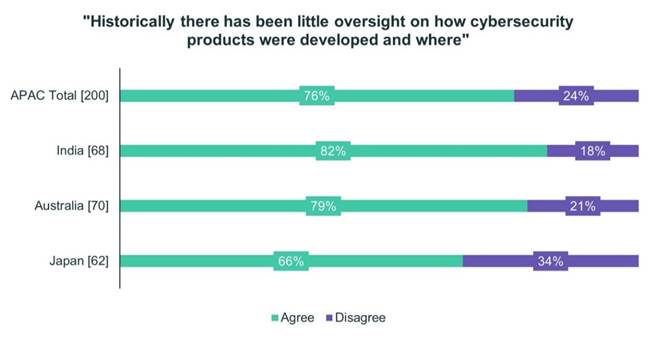

Eighty-two percent of Indian respondents, 79% of Australian respondents and 66% of Japanese respondents voice concerns that there has historically been little oversight over how cybersecurity products themselves were developed and where.

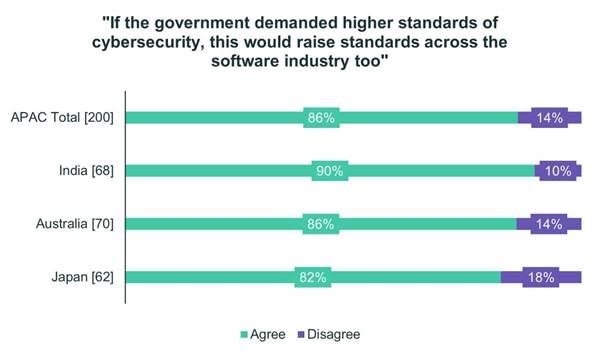

Respondents from India, Australia and Japan agree by wide margins that if government prescribed higher cybersecurity standards, this would raise such standards across the entire software industry.

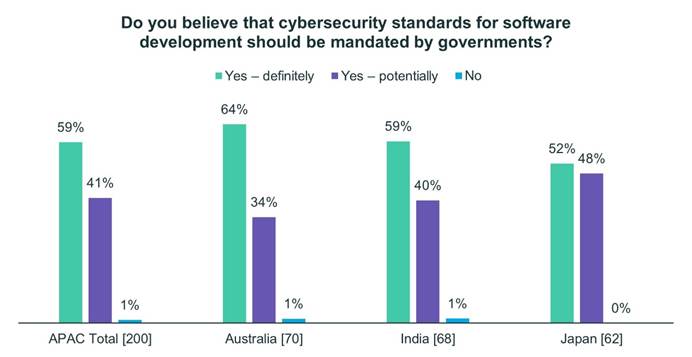

Sixty-four percent of Australian respondents, 59% of Indian respondents and 52% of Japanese respondents support government mandates demanding cybersecurity standards for software.

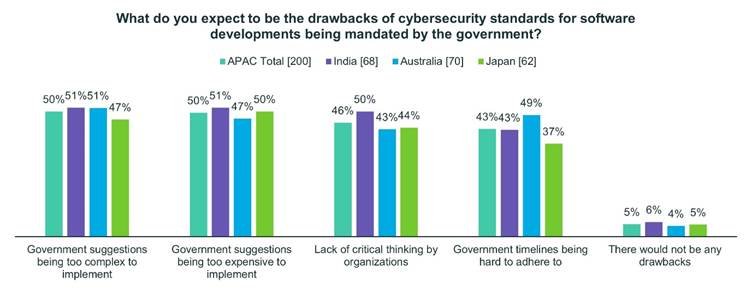

That said, respondents from all three countries have concerns that there could be drawbacks to such standards. Fifty-one percent of Indian respondents believe such mandates could result in government suggestions that are too complex and ultimately too expensive to realistically implement. Around the same number believe that the assertion of such standards could result in less critical thinking on the part of organizations (50%) and just slightly fewer believe the government timelines for these standards could be difficult to meet (43%).

Around half of Australian respondents believe government software security mandates will be too complex (51%) and expensive (47%) to implement and that government timelines will be difficult to meet (49%). Forty-three percent fear standards could result in less critical thinking on the part of organizations.

About half of Japanese respondents are also concerned about the costs (50%) and complexity (47%) of such mandates, with impact to critical thinking and timelines being secondary concerns (by 44% and 37% respectively).

Role of National Governments

Beyond the aforementioned Software Supply Chain Risk measures, the survey found a number of areas where respondents believe their national governments should be playing a stronger role in strengthening their cybersecurity posture.

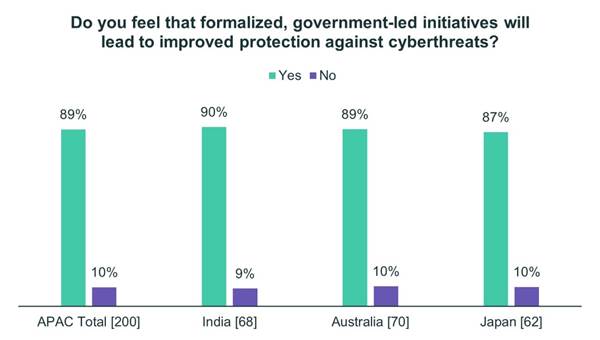

Ninety percent of Indian respondents, 89% of Australian respondents and 87% of Japanese respondents believe that formalized, government-led initiatives will lead to improved protection against cyberthreats. Around the same percentages of Indian (93%), Australian (90%) and Japanese (85%) respondents believe there is room for improvement in terms of the level of partnership between their national governments and organizations based in their country in terms of overcoming cyber-threats.

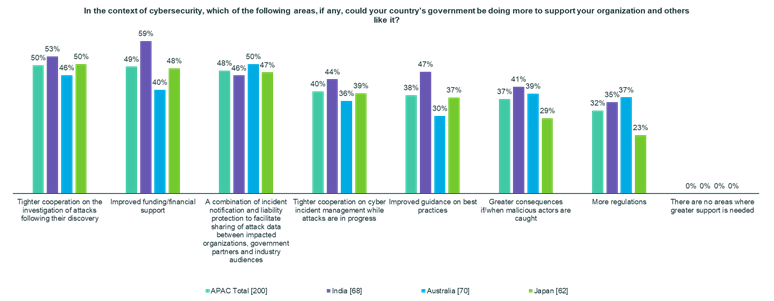

Fifty-nine percent of Indians surveyed believe their government could provide more funding to organizations such as theirs to improve cybersecurity. Fifty-three percent favor tighter cooperation on the investigation of attacks following their discovery, and 44% favored tighter cooperation on cyber incident management while attacks are in progress. Forty-seven percent favor improved guidance on best practices, and 46% favored a combination of incident notification and liability protection to facilitate sharing of attack data between impacted organizations, government partners and industry audiences. Forty-one percent of respondents support greater consequences for malicious actors when caught, and 35% support more regulations of a yet to be determined nature.

Australian respondents showed the most support (50%) for the combination of incident notification and liability protection to facilitate sharing of attack data between impacted organizations, government partners and industry audiences. Forty-six percent favor tighter cooperation on the investigation of attacks following their discovery, while 36% support tighter cooperation on cyber incident management while attacks are in progress. Forty percent support improved cybersecurity funding for organizations such as theirs, 39% favor greater consequences for malicious actors when caught, 37% favor more regulations and 30% favor improved guidance on best practices.

As many as half of Japanese respondents showed support for tighter cooperation on the investigation of attacks following their discovery, followed by more financial support for cybersecurity investments (48%), incident notification and liability protection (47%), tighter cooperation on cyber incident management while attacks are in progress (39%) and improved guidance on best practices (37%).

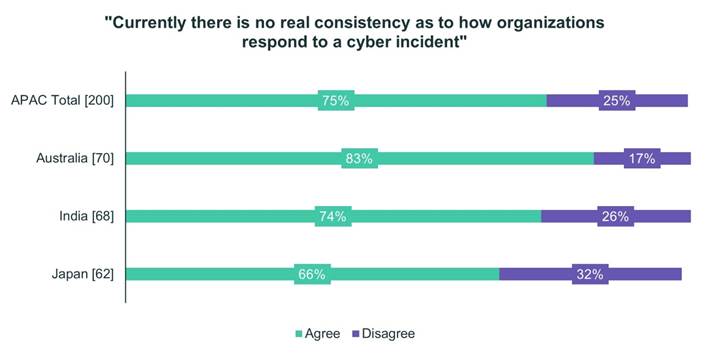

In the area of critical incident response best practices, there is evidence that governments could play a bigger role in providing standardized guidance on how organizations respond to cyber incidents. Eighty-three percent the Australians, 74% of the Indians and 66% percent of the Japanese agree there currently is no real consistency as to how organizations respond in these circumstances.

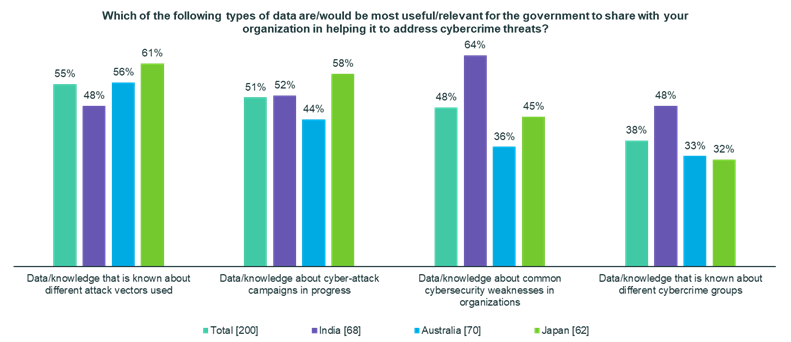

In terms of types of data that would be most useful for their government to share with their organization to help address cyber threats, nearly two-thirds (64%) of Indian respondents valued data about common cybersecurity vulnerabilities in organizations. Fifty-two percent valued data on cyber-attack campaigns in progress, and 48% valued data that is known about different attack vectors and cybercrime groups.

Australian respondents were most likely to value data on different attack vectors used (56%) and data on cyber-attack campaigns in progress (44%) over information on cybercrime groups (33%) and vulnerabilities (36%). Japanese respondents were also most likely to value data on different attack vectors used (61%) and data on cyber-attack campaigns in progress (58%) over information on cybercrime groups (32%) and vulnerabilities (45%).

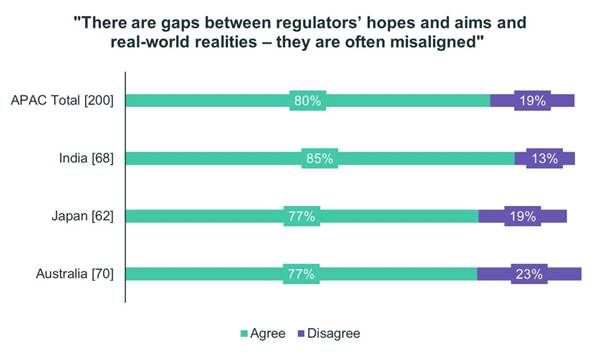

Finally, 85% of Indian respondents, 77% of Japanese respondents and 77% of Australian respondents agree that there are gaps between regulators’ hopes and aims and real-world realities, and that they are often misaligned.

This final finding reminds us that the policies governments must formulate in cybersecurity must be realistic, make the right investments, define the proper public-private roles, set right priorities and establish the right objectives and timelines. Public and private partners must be fully aligned and working together. Only then can nations hope to succeed in better protecting themselves from cyber threats targeting their government agencies and critical infrastructure.

For more information:

RECENT NEWS

-

Jun 17, 2025

Trellix Accelerates Organizational Cyber Resilience with Deepened AWS Integrations

-

Jun 10, 2025

Trellix Finds Threat Intelligence Gap Calls for Proactive Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation

-

May 12, 2025

CRN Recognizes Trellix Partner Program with 2025 Women of the Channel List

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Details Surge in Cyber Activity Targeting United States, Telecom

-

Apr 29, 2025

Trellix Advances Intelligent Data Security to Combat Insider Threats and Enable Compliance

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.