Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

2022 Election Phishing Attacks Target Election Workers

By Rohan Shah · October 12, 2022

This blog was written by Patrick Flynn and Fred House

Highly publicized campaign and political party breaches during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign raised election security as a critical issue among U.S. policy makers in the years that followed. These concerns peaked leading up to and during the 2020 U.S. Presidential election, and efforts by the Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency (CISA) and other government entities at the federal, state and local level have made critical progress towards more effectively securing national and state elections.

The election of President Joe Biden and subsequent challenges to this 2020 result understandably shifted national media and policymaker attention away from foreign attacks on election systems to domestic partisan disinformation about election results and physical threats towards election officials and their frontline employees.

But, while U.S. elections have indeed become more secure than ever before, Trellix has identified efforts to target county-level election workers in the digital realm even as these same workers have become the targets of threats and intimidation in the physical realm.

Over much of the last year, Trellix’s global network of threat sensors and the Trellix Advanced Research Center have identified a surge in malicious email activity targeting county election workers in the key battleground states of Arizona and Pennsylvania coinciding with these states’ primary elections. In investigating the nature of this activity, Trellix identified a familiar password theft phishing scheme as well as a newer phishing scheme seeking to prey on the absentee ballot administration process.

This first in a series of Trellix 2022 Election Security blogs focuses on these malicious emails targeting county workers managing local election infrastructure. Trellix focused this initial research at the county-level given these election authorities are relatively the least sophisticated actors in terms of cybersecurity postures, but the most critical in actual electoral engagement with voters. Our findings suggest the continuing effort to educate frontline election workers on phishing and other cyber threats in the digital realm could be as important as security measures required to protect them in the physical realm in 2022 and beyond.

The primary surge

The months leading up to a state’s primary elections are known for intense flurries of activity among election administrators as they work quickly to register voters, inform them of logistics and processes, and then execute the actual primary elections.

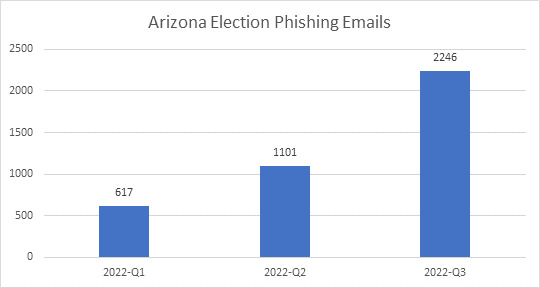

In Arizona, Trellix observed a surge in malicious email detections peaking around the Grand Canyon State’s August 2 primary elections. They rose 78% from 617 in Q1 of 2022 to 1,101 in Q2. They rose again 104% to 2,246 by the third quarter.

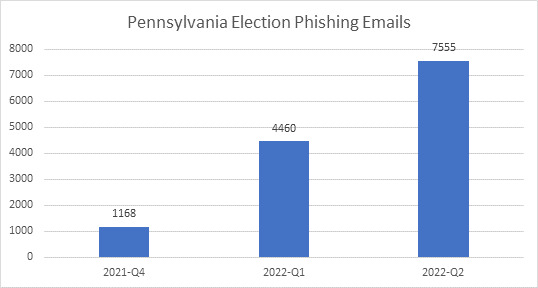

Trellix Advanced Research Center detected a similar surge in malicious emails targeting county election workers in the battleground state of Pennsylvania leading up to its primaries on May 17. The Keystone State saw malicious email detections rise 282% from 1,168 in Q4 of 2021 to 4,460 in the first quarter of 2022. They then rose another 69% to 7,555 by the end of the second quarter.

The “primary surge” reminds us the national issue of election security is very much a state and local issue with which state and local entities and infrastructure must wrestle. Furthermore, states and localities do not operate on an equal cybersecurity footing. Some will be more susceptible to attacks than others and many will continue to require the help of the federal government to not only harden themselves to these and other attacks, but also educate local election employees in cyber hygiene to thwart them at their point of attack.

Phish #1: Password theft

In March 2016, John Podesta, the chair of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 U.S. presidential campaign fell victim to a spear-phishing email attack that compromised his Gmail account and led to the politically damaging leak of more than 20,000 pages of email to WikiLeaks. In monitoring malicious email detections across counties in battleground states in 2022, Trellix identified a phishing tactic like that used on Mr. Podesta.

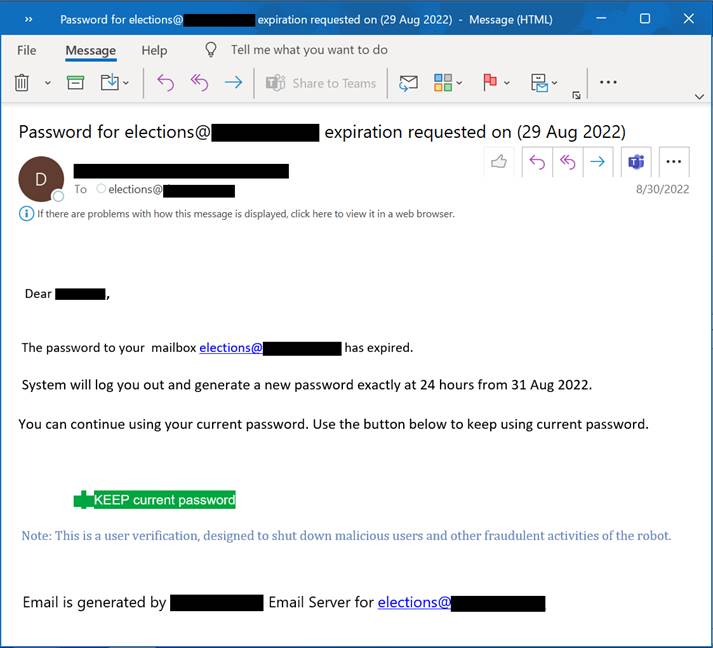

It uses a fraudulent password expiration alert to lure election workers to a bogus administrative webpage where they are prompted to enter their current username and password login credentials.

The attacker’s phishing email informs the user that her password is about to expire, at which time she will lose the network access she needs to complete the tasks her job requires.

The election worker fears her organization’s IT administrator is urgently beckoning her to change her password before she is locked out and cannot do her job. If she clicks on the email links, she is taken to a landing page where she is told she can keep or change her password if she submits her current username and password and a new password (if she chooses).

At this point, the attacker has possession of the user’s login credentials and can use them to access whatever organizational assets she can access across the election administrator’s networks.

The attacker could access election process documents, voter records, colleague contact lists, administrative tools and a variety of other documents and forms. The attacker could send voters incorrect election process information to mislead them into invalidating their votes or create confusion in the lead up to election day that undermines their confidence in the process.

The attacker could identify other officials via organizational contact lists and use them to target individuals who might have higher level access to more critical election and voting tabulation processes.

Finally, the attacker could sell the stolen credentials on an underground forum to nation state actors or other malicious parties, such as ransomware operators capable of locking up key systems just days before the election.

The attackers are using this login credentials phishing scheme because it has proven so successful across all areas of cybercrime. Users in any organization are likely to trust emails from their IT administrators and they are more likely to be concerned with losing access to their work assets than suspect being the potential target of a phishing attack.

Such attacks can also be easily automated across numerous target user email accounts in the hope that at least a couple election workers might be careless enough to play along as John Podesta did in 2016.

Phish #2: Trusted thread, poisoned link

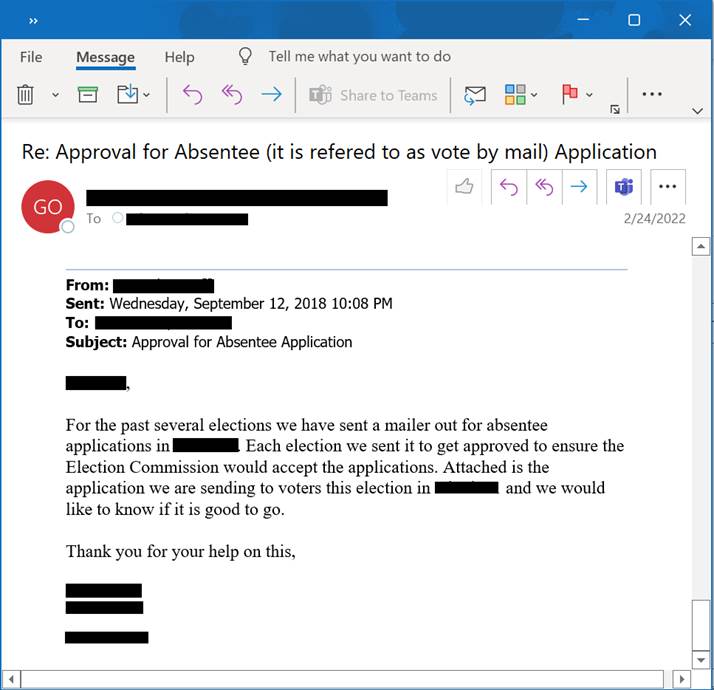

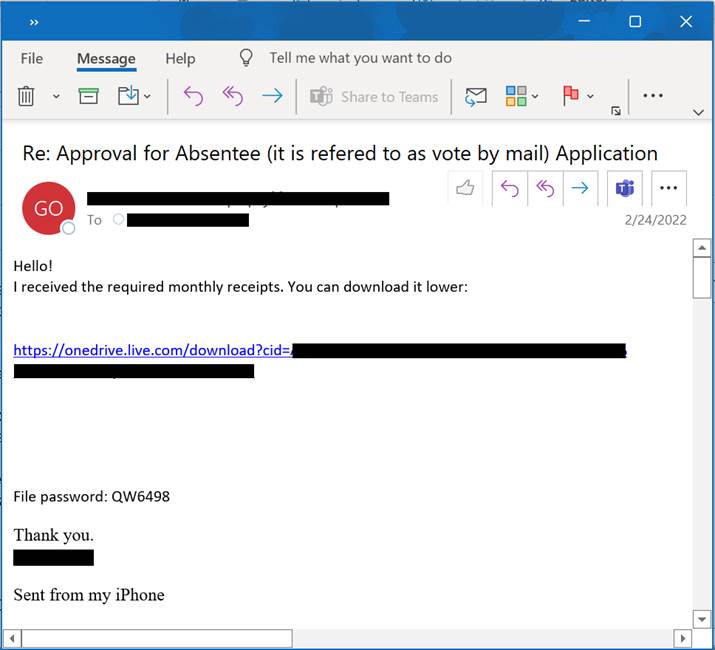

Trellix observed a second notable phishing scheme preying on correspondence between a county election worker and a government contractor distributing and collecting absentee ballot applications.

The attacker leverages either a compromised email thread or forged email thread dating back to 2018 between an election worker and the contractor. The email thread is presumably a familiar correspondence, making it more likely that the election worker trusts the interaction with the sender.

Many threat actors such as QBot, Hancitor, Emotet and others have been known to steal and use email threads that make it possible to target specific victims more effectively. These actors have found success in using such trusted email correspondence to deliver malicious documents (.zip, .pdf, .docx, etc.) or malicious download links such as that used in this sample.

The election administrator replies to make himself as helpful as possible to someone posing as a trusted partner in the election process. The attacker sends a Microsoft OneDrive link from which the election worker can download the completed absentee ballot applications.

Unfortunately, the download is poisoned with malware capable of infecting the election employee's system and perhaps gaining access to other systems across his organization’s networks.

This second scheme is more involved than the first in that it requires the attacker to obtain a real, trusted email thread through a breach or forge an email thread based on the attacker’s knowledge of the election employee’s email address and that of the contractor contact.

Trellix cannot confirm whether the thread dating back to 2018 is the result of a breach or a clever forgery. Nor can we confirm whether this correspondence is automated or manual. Trellix can confirm this phishing email was blocked through the detection of the malicious Microsoft malware download.

Ultimately, this phishing scheme plays on the election worker’s professional and moral commitment to help a trusted contractor struggling to register people to vote. It relies on the election officials’ willingness to perhaps step outside an established submission process and click on the attacker’s poisonous link to access the voter applications.

While Trellix has no evidence of election systems being compromised in any state or county. While we cannot establish attribution, our investigations into 2022 election-related cyber activity are ongoing and we will make more information available when possible.

How organizations can protect themselves

Organizations can implement any number of email security solutions to protect themselves from such phishing attacks. They can also take advantage of anti-phishing features offered by their email clients and web browsers.

The federal government is providing tools, services, funding and information resources for state and county election administrators working to harden their information technology (IT) systems to cyber-attacks. These efforts also include information resources from CISA providing specific guidance on how election officials can educate their employees on how to avoid falling victim to phishing campaigns and other social engineering schemes.

While these federal efforts have been invaluable in helping state and local governments improve their cybersecurity posture, Trellix believes there is value to disclosing these phishing emails as educational examples to warn election officials across the country of the types of schemes attackers might use to target their employees.

As recently as October 5, CISA and the FBI warned of phishing emails targeting individuals associated with the U.S. electoral process in a joint statement:

- “Be wary of emails or phone calls from unfamiliar email addresses or phone numbers that make suspicious claims about the elections process or of social media posts that appear to spread inconsistent information about election-related incidents or results.

- Do not communicate with unsolicited email senders, open attachments from unknown individuals, or provide personal information via email without confirming the requester’s identity. Be aware that many emails requesting your personal information often appear to be legitimate.”

Educating employees on the need to recognize suspicious emails should not stop because we are making cybersecurity progress in other areas. Education on cyber hygiene is an ongoing, never-ending process, particularly as attackers innovate and improve upon their phishing and social engineering techniques.

Here are some cyber hygiene tips to address these phishing email threats:

- Beware of emails with urgent calls to action, such as password changes. To guard against the password phishing scheme, users should be wary of urgent calls to action, particularly those warning without precedent that they must immediately click through to a website and share their passwords. The attacker is creating a false sense of urgency to prompt user action. Users should recognize this as suspicious given that IT administrators usually send multiple warning messages to alert them of upcoming password deadlines.

- Check the email address of the sender. The user can check the email domain from which the email is sent. If the email domain is not that of the user’s organization, that should be a dead giveaway that it should not be trusted. This email domain check is relevant to the second phishing scheme as well as the employees should be able to recognize that the email domain is different from the third-party contractor.

- Beware of file download links as well as weblinks from suspicious sources. The election worker should also be wary of anyone sending mysterious download or website links that really are not necessary given that completed applications can be sent via email or uploaded through the administrators’ established websites. Any effort to suggest workers should step out of the established processes to use a download link or go to a random web page should be questioned.

- When in doubt, contact your IT or cybersecurity teams. Election workers should forward any suspicious emails they receive to their IT departments and cybersecurity teams. Let the professionals sort the matter out from there.

Election security + election disinformation

Trellix will continue to share what it has found and learned to encourage adoption of stronger cybersecurity practices within organizations managing elections.

Despite the tremendous progress made since 2016, Trellix believes U.S. election officials should focus on the human aspects of election cybersecurity as well as election disinformation and election workers’ physical security. Any apparent cyber incidents around the 2022 midterms could potentially be used to feed more election result conspiracy theories.

Ultimately, stronger cybersecurity solutions and cyber hygiene practices are in themselves a strong bulwark against disinformation and the corrosive effect it has on citizen confidence in democracy.

The next blog in this series will challenge the many election security disinformation myths circulating across traditional and social media since 2020.

RECENT NEWS

-

Mar 02, 2026

Trellix strengthens executive leadership team to accelerate cyber resilience vision

-

Feb 10, 2026

Trellix SecondSight actionable threat hunting strengthens cyber resilience

-

Dec 16, 2025

Trellix NDR Strengthens OT-IT Security Convergence

-

Dec 11, 2025

Trellix Finds 97% of CISOs Agree Hybrid Infrastructure Provides Greater Resilience

-

Oct 29, 2025

Trellix Announces No-Code Security Workflows for Faster Investigation and Response

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.