Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

The Evolution of Russian Physical-Cyber Espionage

By Ryan Slaney · October 6, 2025

Russian state-sponsored cyber operations, primarily those conducted by hackers belonging to its Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU), also known as APT28, have long combined digital intrusions with physical tradecraft and human assets. From headline-grabbing leaks during the Rio Olympics, to GRU operatives caught red-handed in The Hague, and most recently allegations of teenagers recruited to deploy Wi-Fi sniffers near EU institutions, a consistent picture emerges: Moscow’s intelligence services continue to rely on close access operations that blur the line between cyber and physical espionage.

APT28 targets anti-doping bodies

The first known wave of Russian state-sponsored close access activity unfolded during the 2016 Rio Olympics. APT28 spear-phished officials at the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), gaining access to the ADAMS database of athlete therapeutic use exemptions. Soon after, medical records of U.S. and international athletes were leaked in an apparent attempt to discredit anti-doping enforcement and cast doubt on competitors’ legitimacy. Two years later, in April 2018, Dutch authorities closely watched as a team of four Russian close access operators arrived by air in The Hague. They followed the team from the shadows as they rented a car, picked up supplies, and began driving around the city, taking pictures of various international organizations.

Russia’s campaign did not stop at WADA. APT28 also went after the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES), Canada’s national anti-doping agency.

These attacks were a direct result of Russia’s frustration at seeing its athletes banned from competing under the Russian flag during the Rio Olympics due to the exposure of its state-sponsored doping program in the previous Sochi Olympics. By hacking ADAMS and releasing Therapeutic Use Exemptions (TUE) of international athletes, Moscow aimed to retaliate, discredit anti-doping agencies, and reinforce Russia’s perceived double standard of how its athletes were treated compared to those from Western countries.

The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) incident: GRU operatives on Dutch soil

Two years later, in April 2018, Dutch authorities closely watched as a team of four Russian close access operators arrived by air in The Hague. They followed the team from the shadows as they rented a car, picked up supplies, and began driving around the city, taking pictures of various international organizations.

After observing the team park at the Marriott hotel across from the OPCW and aim their electronic equipment towards the OPCW offices, the authorities realized the team's primary target. They decided to confront the men before it was too late.

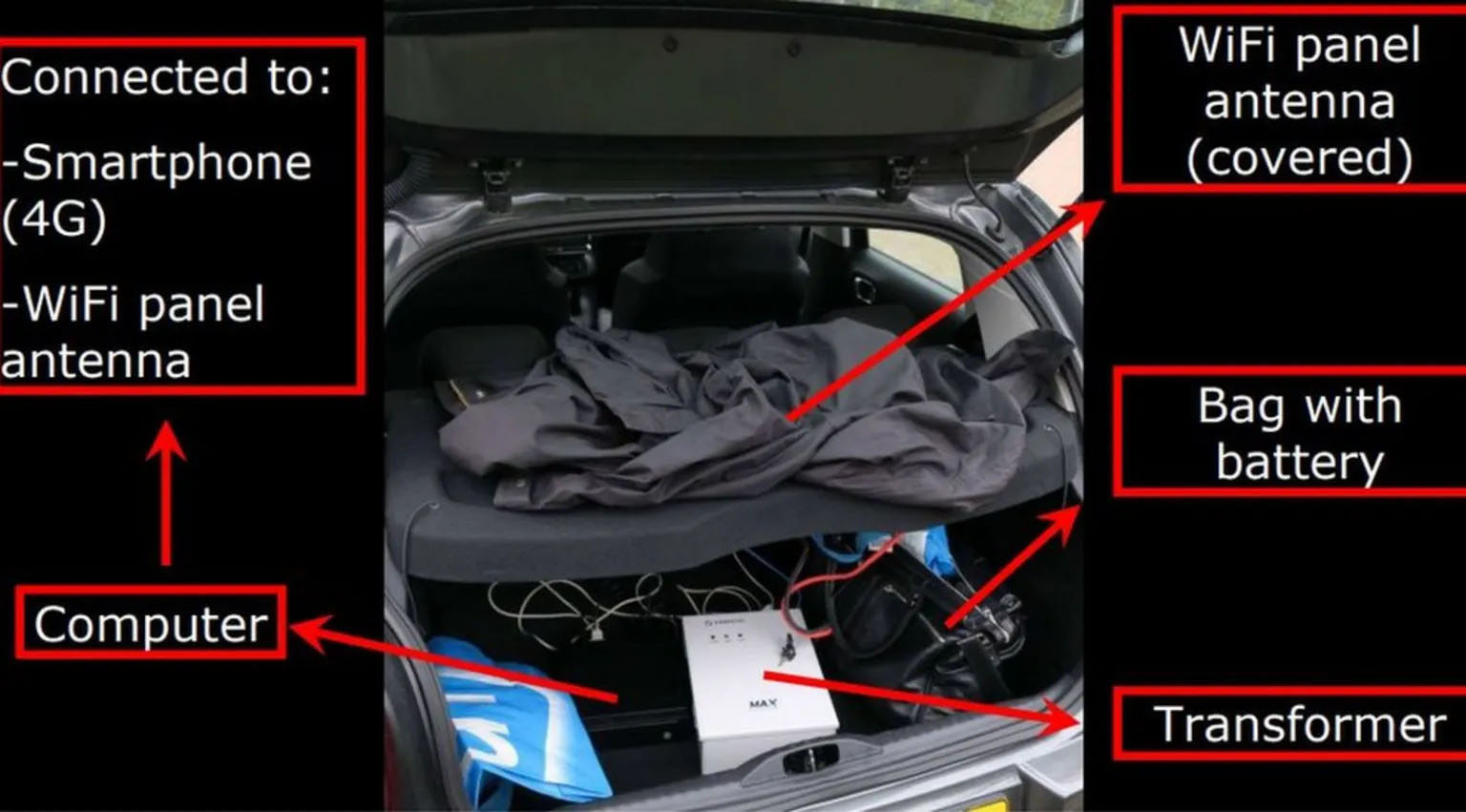

The police caught the Russian team, who had operated with impunity up to that point, completely off guard and red-handed. Despite their attempts to destroy some equipment, namely a very durable Nokia mobile phone (pictured below), the Dutch authorities recovered an array of equipment and other items in the team’s possession, including:

- Laptops configured to connect directly to the OPCW’s Wi-Fi network.

- Specialized antennas and a Wi-Fi transceiver concealed in the trunk of a rented Citroën hatchback.

- Mobile phones, some of which were linked to previous operations in Switzerland.

- €20,000 in cash and $20,000 in U.S. dollars, likely for operational expenses and emergencies.

- Taxi receipts from Moscow, place them at a GRU headquarters before departure — an attribution goldmine and serious lapse in operational security on behalf of the GRU team. These were likely kept so the actors could claim expenses upon their return to Moscow.

The Dutch government publicly expelled the men and, in an unusual move, released photographs of their passports, equipment, and travel itineraries. The team consisted of the following individuals:

- Aleksei Morenets – an officer specializing in cyber operations.

- Evgenii Serebriakov – an IT specialist (later indicted in the U.S. for GRU cyber campaigns).

- Oleg Sotnikov – logistics support, driver.

- Alexandr Minin – operations officer, field support.

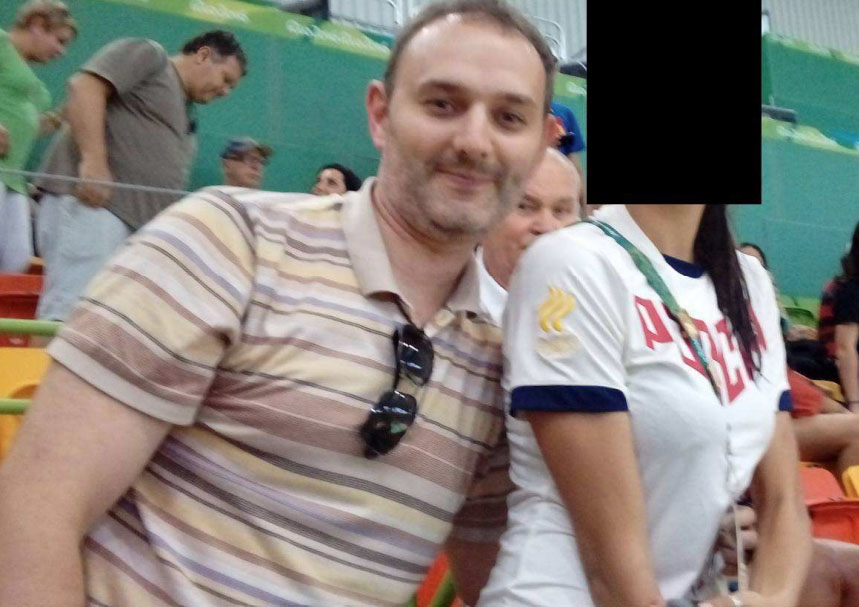

Analysis of the devices the operators were ‘relieved of’ provided evidence of previous attacks the group had conducted. For example, investigators found a picture on Serebriakov’s laptop of him and a Russian athlete taken during the Rio Olympics, proving he was physically in Brazil when ADAMS was compromised.

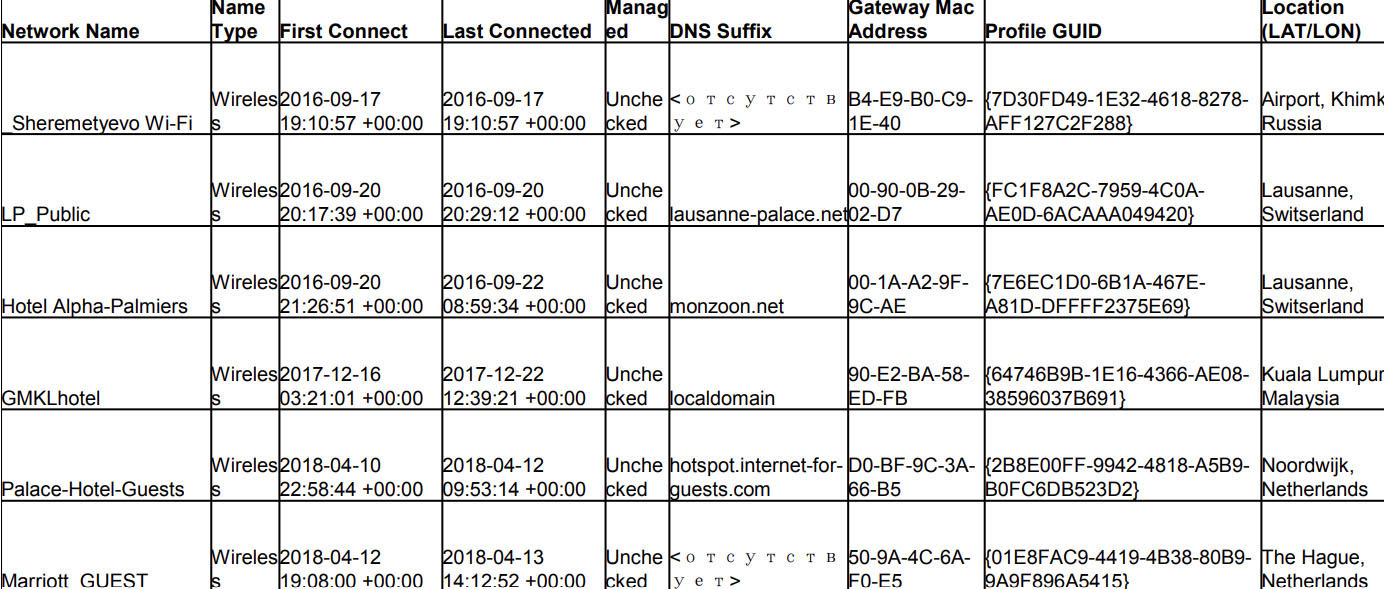

Investigators also discovered the team’s laptops and phones had connected to Wi-Fi networks in various countries at locations close to where other attacks were suspected to have occurred, such as Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, where authorities were investigating the downing of Flight MH70 suspected to have been caused by a Russian surface-to-air missile, and a hotel in Lausanne, Switzerland, where a high level WADA conference previously took place.

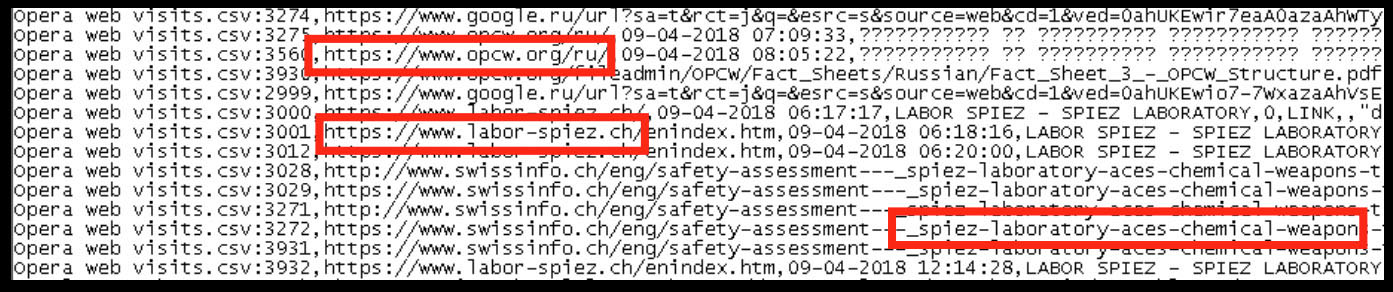

Not only did investigators discover what the team had been up to, they also learned what they intended to do. Further analysis of the confiscated devices revealed the team purchased train tickets to travel to Bern, Switzerland, after completing their mission in The Hague, and had conducted Google searches for the Spiez Laboratory. The Spiez Laboratory is the Swiss institute responsible for protecting the population against nuclear, biological, and chemical threats and dangers. Russia likely believed the Swiss lab was assisting the OPCW in its investigation; thus, the team was instructed to compromise it in a similar manner.

The intelligence gleaned from the aftermath of the failed Hague operation underscored the boldness of the GRU’s close access team’s activities. However, it also revealed the team had become careless and committed several serious operational security lapses, which ultimately led to its demise and left the Russian government exposed to diplomatic complications.

Despite Serebriakov’s failure as team leader to ensure operational security and to complete his mission, the GRU not only decided to keep him employed, but later placed him in charge of the GRU’s infamous Unit 74455, a highly sophisticated group of hackers that specialize in destructive cyber operations primarily targeting critical national infrastructure (CNI), industrial control systems (ICS), and entities of strategic interest to Russia, including Ukrainian military and governmental targets. Some of Unit 74455’s most notable attacks include the successful deployment of BlackEnergy malware in Ukraine in 2015, as well as NotPetya and BadRabbit ransomware in 2017.

The “nearest-neighbor” evolution

Now that the GRU’s premier close-access team had been sidelined, likely permanently, Russian services had to adapt. One emerging tactic has been dubbed the “nearest-neighbor” attack. Instead of breaching secure networks directly, attackers exploit nearby devices or networks that bridge into sensitive environments. In short, rather than attacking the fortress, an adversary breaks into the house across the street and climbs over the fence. This often means:

- Leveraging dual-homed hosts (machines with both internal wired and external wireless access).

- Deploying sniffer hardware to capture traffic or credentials.

- Recruiting local assets to position the collection devices within range physically.

This approach allows Moscow to circumvent hardened perimeters, minimize its own footprint, and gain plausible deniability.

In November 2024, cybersecurity researchers at Volexity revealed a novel nearest‑neighbor-style attack launched by APT28 to gain covert access to a targeted organization by compromising nearby organizations and “daisy‑chaining” through their networks until it could authenticate to the target’s enterprise Wi‑Fi. The technique exploited the fact that the target’s Wi‑Fi accepted only username/password (no MFA), while Internet‑facing services required MFA — so APT28 brute‑forced or validated credentials remotely, then used a proximate, compromised dual‑homed host to physically connect to the target Wi‑Fi and pivot inside.

Volexity’s investigation revealed that APT28 succeeded in accessing the target via the nearest‑neighbor chain and that it returned at least once after remediation attempts, using additional fallback through the guest Wi‑Fi before being expelled. The intrusion allowed access to sensitive artifacts (e.g., registry hives) and demonstrated APT28’s sophisticated persistence and anti‑forensics capabilities.

Despite APT28’s apparent success during this attack, there has been no evidence of any Russian actor using this attack vector since this particular attack. One probable reason is that nearest‑neighbor attacks demand substantially more planning, logistics, and local access than typical remote intrusions. They also require physical reconnaissance, compromise or recruitment of proximate hosts, and sometimes on‑the‑ground hardware (directional antennas, sniffers, rogue APs). This complexity increases mission costs, reduces scalability, and introduces dependencies (finding a suitable dual‑homed host or willing local asset) that aren’t necessary for phishing, supply‑chain, or malware campaigns.

More importantly, the approach raises exposure and attribution risk as Wi‑Fi controllers, RADIUS logs, MAC addresses, and physical surveillance/parking records create multiple correlation points investigators can use to trace activity back to specific actors.

Additionally, the Volexity disclosure and related public reporting forced defenders to harden their wireless controls and logging, thus lowering the method’s payoff. Nearest‑neighbor attacks may work in narrow, situational contexts but are likely considered too risky, costly, and difficult to scale for routine use by a persistent actor like APT28.

Russia returns to The Hague

Fast-forward to 2025, and it would appear that Russian intelligence has returned to The Hague, albeit in a much different form. Dutch media recently reported that two 17-year-old boys were arrested in The Hague, accused of operating a Wi-Fi sniffer near the offices of Europol, Eurojust, and the Canadian embassy. The reports suggest they may have been recruited or paid by Russian handlers to collect signals intelligence and information on Wi-Fi networks in support of or to facilitate a nearest-neighbor style operation.

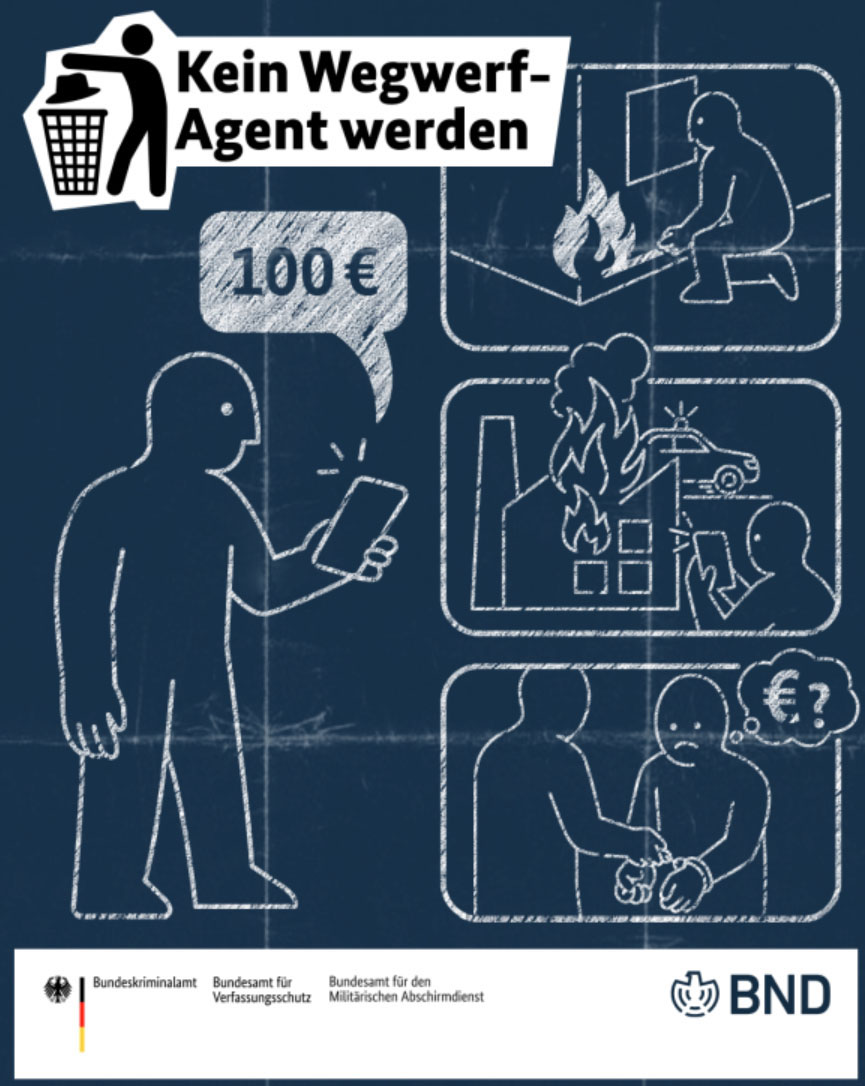

German authorities had previously sounded the alarm regarding this type of activity, warning citizens that taking part in any espionage or sabotage activity is a serious crime.

While investigations are ongoing, the case is striking. Instead of GRU officers flying in with antennas and cash, local teenagers with commodity hardware are now allegedly serving as Moscow’s forward collectors. If true, it demonstrates how Russia continues its history of outsourcing the riskiest elements of its cyber operations to expendable, deniable proxies.

Conclusion and Outlook

Russia has a long, well-documented practice of outsourcing offensive cyber tasks to criminal hackers and pro-Russian hacktivist collectives. Many high-profile legal cases detailed how FSB officers allegedly directed or paid outside hackers (e.g., the Karim Baratov case and the long-wanted Aleksey Belan) to carry out credential theft and large-scale intrusions. At the same time, groups such as CyberBerkut and NoName057(16) have operated as deniable DDoS/leak and influence proxies that amplify Kremlin objectives. In short, Moscow has habitually combined state planning with external technical labor to scale campaigns, complicate attribution, and reduce direct exposure of official units.

What appears new is the extension of that outsourcing model into physical, close-access collection with the allegations that local, low-risk assets were paid or recruited to operate Wi-Fi sniffers near high-value targets. If confirmed, this activity represents a significant tactical shift, yet it remains consistent with Russia’s overall cyber modus operandi: using every available vector — cyber, physical, and human — to undermine adversaries while avoiding direct confrontation and thus ensuring plausible deniability.

Whether through elite GRU units with antennas in a car park or teenagers with a Wi-Fi sniffer outside embassies, Moscow has shown a willingness to innovate and adapt in pursuit of access to the information it requires, an endeavor that’s not likely to stop any time soon.

Implications for defenders

For organizations in the crosshairs, defending against Russia’s covert access operations requires a multi-layered approach to cybersecurity. Defenders can significantly reduce risk from nearest-neighbor, close-access, and hybrid cyber-physical operations by deploying Trellix’s integrated security solutions. Trellix’s endpoint protection and advanced detection technologies can identify unusual lateral movement and credential misuse, while network and Wi-Fi monitoring tools detect rogue access points, anomalous authentication events, and suspicious traffic from nearby networks. Combined with threat intelligence and managed detection services, Trellix enables organizations to correlate wireless, endpoint, and network telemetry, rapidly uncover attacks exploiting proximate devices or dual-homed hosts, and respond before adversaries achieve persistent access.

Trellix recommends that network defenders also adopt the following measures to mitigate the risk associated with nearest-neighbor and close access attacks:

- Wireless anomaly detection: monitor for rogue devices, sniffers, and unusual probe requests near facilities.

- Eliminate dual-homed systems: prevent guest Wi-Fi or personal devices from bridging into internal networks.

- Physical and human security: conduct RF sweeps, vet contractors, and watch for local recruitment efforts.

- Fusion of cyber and HUMINT: integrate digital forensics with law enforcement and counterintelligence insights.

Discover the latest cybersecurity research from the Trellix Advanced Research Center: https://www.trellix.com/advanced-research-center/

RECENT NEWS

-

Feb 10, 2026

Trellix SecondSight actionable threat hunting strengthens cyber resilience

-

Dec 16, 2025

Trellix NDR Strengthens OT-IT Security Convergence

-

Dec 11, 2025

Trellix Finds 97% of CISOs Agree Hybrid Infrastructure Provides Greater Resilience

-

Oct 29, 2025

Trellix Announces No-Code Security Workflows for Faster Investigation and Response

-

Oct 28, 2025

Trellix AntiMalware Engine secures I-O Data network attached storage devices

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.