Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

The Hermit Kingdom’s Ransomware play

By Trellix · May 3, 2022

(With a special thanks to @ValidHorizon who helped and shared information)

In February 2016, news broke about what is now known as the ‘Bangladesh Bank Heist’. Hackers attempted to transfer nearly one billion USD through the SWIFT system towards recipients at other banks. The investigation, performed by several US agencies, lead to a North Korean actor, dubbed ‘Hidden Cobra’. Ever since then, the group has been active, compromising numerous victims. One notable case is at a Taiwanese bank where ransomware was used to distract the incident response team, allowing the actor to transfer funds to other bank accounts in the APAC region.

Hidden Cobra and other groups named by the industry are part of North Korea’s cyber-army. The cyber-army of North Korea has been divided in several units, all of which have different tasks and report to ‘Bureau (or Lab) 121’. The unit responsible for the attacks on foreign financial systems, including banks and cryptocurrency exchanges, is Unit 180, which is also known as APT38. While domestic nuclear and missile programs are funded with stolen money, the actors of Unit 180 mostly reside in overseas countries such as China, Russia, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh, Indonesia, India, Kenya, and Mozambique. The varying geographical locations are likely an attempt to conceal the unit’s link to the hermit kingdom that is North Korea. It’s also important to note defectors have exposed that obtaining funds for the government is done by more actors than the country’s ‘elite hackers’.

Over time we have observed several methods North Korea has used to gain money. Although not as frequently observed as other groups, there have also been attempts made to step into the world of ransomware.

While ransomware is mostly a cybercriminal play, in March 2020, a new malware family surfaced called ‘VHD ransomware’. Another day, another ransomware family. So, what is new? Many in the industry attributed the VHD ransomware to DPRK hackers. It was distributed using the MATA framework, which has been attributed to the hermit kingdom. The ransomware itself contained enough unique artifacts to also link it to said kingdom.

Around that time, we conducted joint research with regards to code similarity in DPRK’s malware. In this blog, we continue this research by looking at the VHD ransomware’s code-similarity, artifact similarity, graph science, and Bitcoin addresses and transfers.

Let’s go hunting

Using the source-code of the VHD ransomware family, several interesting function blocks were identified as potential candidates for reusage. Why rebuild the whole car while you still have usable parts? Using those blocks as a starting point, a hunt was started from March 2020 onwards to discover related families.

The initial results were promising, and with a bit of filtering and the removal of false positives, the following families were identified:

- BEAF ransomware

- PXJ ransomware

- ZZZZ ransomware

- CHiCHi ransomware

Aside from the code-similarity hunting, reports also mentioned the spread of the ‘Tflower ransomware’ family via the aforementioned MATA framework. Another observation is that the four letters of the ransomware “BEAF” (BEAF is the extension used for the encrypted files), are exactly the same first four bytes of the handshake of APT38’s tool known as Beefeater.

Code similarity

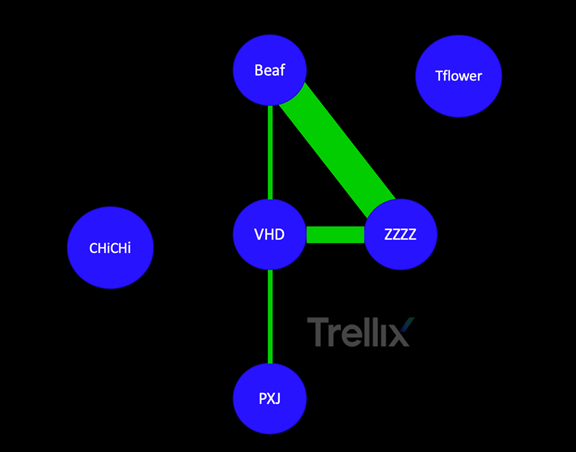

Using tools like BinDiff, we started to compare the ransomware families from a code perspective, as is shown in the figure below.

This graph shows three families which share a significant amount of code with the VHD source code. The ZZZZ ransomware is almost an exact clone of the Beaf ransomware family. The Tflower and ChiChi families do share some little code with VHD, but that would be more generic functions than typical shared code and functionality, hence we did not visualize that.

Code visualization

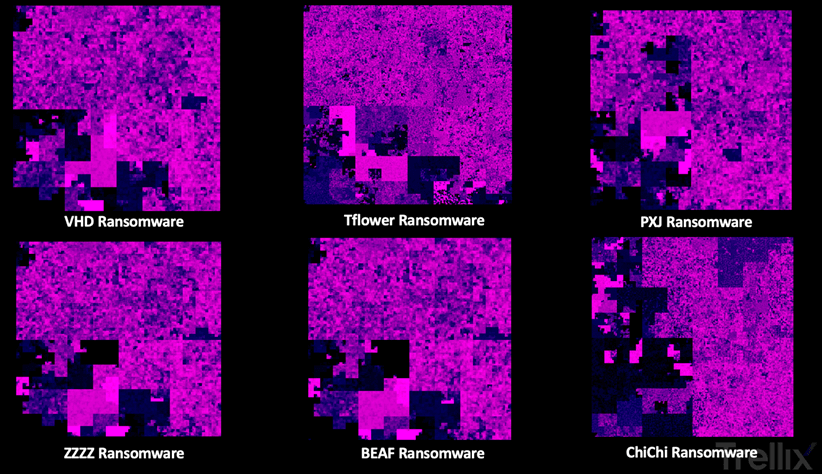

There are several ways of looking at code, one of which entails visualizing the code and comparing the images. One way to visualize data, is by creating a Hilbert curve mapping, which is used to map a string of data into an alternate dimensional space. Generating the graphics for the six families results in the following overview:

You don’t have to be a malware specialist to immediately recognize that the ZZZ and BEAF Ransomware pictures are almost identical. It also becomes apparent that both Tflower and ChiChi are vastly different when compared to VHD.

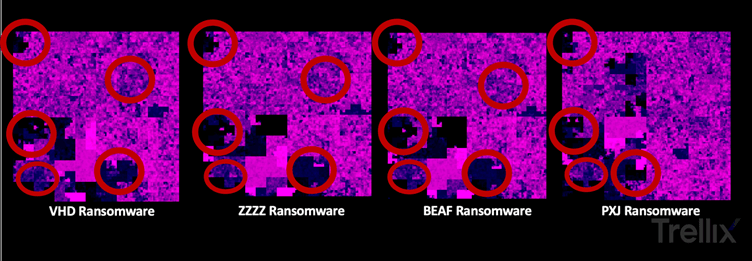

In the code-similarity comparison between the code blocks, several overlaps were found. Comparing the Hilbert curves of these families, similar patterns are now visualized.

While comparing the content of the ransomware notes, the email address Semenov[.]akkim@protonmail[.]com was present in samples of both the ‘CHiCHi’ and ‘ZZZZ’ ransomware families.

Follow the money

The families we investigated were not widespread and seemed to be directed at specific targets in the APAC region. Besides some reports, not much is known about the victims as there were no leak pages or negotiation chats, which are now common for groups to utilize.

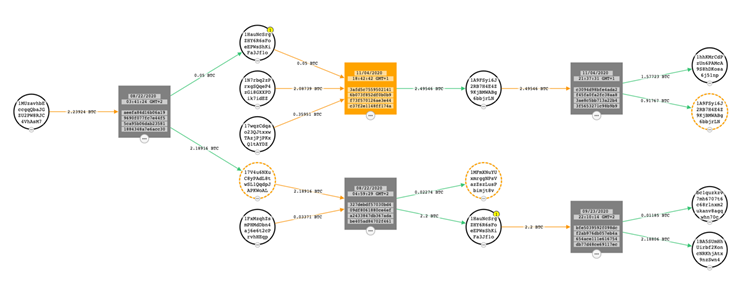

To understand if we could discover financial trails with an overlap between the families, we extracted the Bitcoin (BTC) wallet addresses and started tracing and monitoring the transactions.

We did not find any overlap in transfer wallets between the families. We did find, however, that the paid ransom amounts were relatively small. For example, a transaction of 2.2 BTC in mid-2020 was worth around 20K USD. It was transferred multiple times through December 2020. At that time, a transaction took place towards a bitcoin exchange to either cash out (as the value had roughly doubled) or exchange for a different and less traceable cryptocurrency.

Summary

Over the last few years, we have followed DPRK attacks on financial institutions. Besides global banks, blockchain providers and users from South Korea were also attacked and infiltrated using spear-phishing emails, fake mobile applications, and even fake companies. Since these attacks were predominantly observed targeting the APAC region with targets in Japan and Malaysia for example, we anticipate these attacks might have been executed to discover if ransomware is a valuable way of gaining income.

We suspect the ransomware families described in this blog are part of more organized attacks. Based on our research, combined intelligence, and observations of the smaller targeted ransomware attacks, Trellix attributes them to DPRK affiliated hackers with high confidence.

RECENT NEWS

-

Feb 10, 2026

Trellix SecondSight actionable threat hunting strengthens cyber resilience

-

Dec 16, 2025

Trellix NDR Strengthens OT-IT Security Convergence

-

Dec 11, 2025

Trellix Finds 97% of CISOs Agree Hybrid Infrastructure Provides Greater Resilience

-

Oct 29, 2025

Trellix Announces No-Code Security Workflows for Faster Investigation and Response

-

Oct 28, 2025

Trellix AntiMalware Engine secures I-O Data network attached storage devices

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.