Blogs

The latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and more

The Coordinated Embassy Hunt: Unmasking the DPRK-linked GitHub C2 Espionage Campaign

By Pham Duy Phuc and Alex Lanstein · August 18, 2025

The Trellix Advanced Research Center uncovered a sophisticated espionage operation targeting diplomatic missions across several regions in South Korea during early 2025. Between March and July 2025, DPRK-linked actors are believed to have carried out at least 19 spear-phishing email attacks against embassies worldwide, impersonating trusted diplomatic contacts and luring embassy staff with credible meeting invites, official letters, and event invitations.

The attackers leveraged GitHub, typically known as a legitimate developer platform, as a covert command-and-control channel. To distribute their malware, they relied on common cloud storage solutions like Dropbox and Daum, deploying a variant of XenoRAT remote access trojan that provided complete system control for intelligence gathering. Key infrastructure analysis linked this campaign to known Kimsuky operations [1], with C2 servers matching previously identified DPRK espionage infrastructure.

This campaign remains active and ongoing, with the analysis cut-off date for this report being July 28th, 2025.

Infection chain and technical analysis

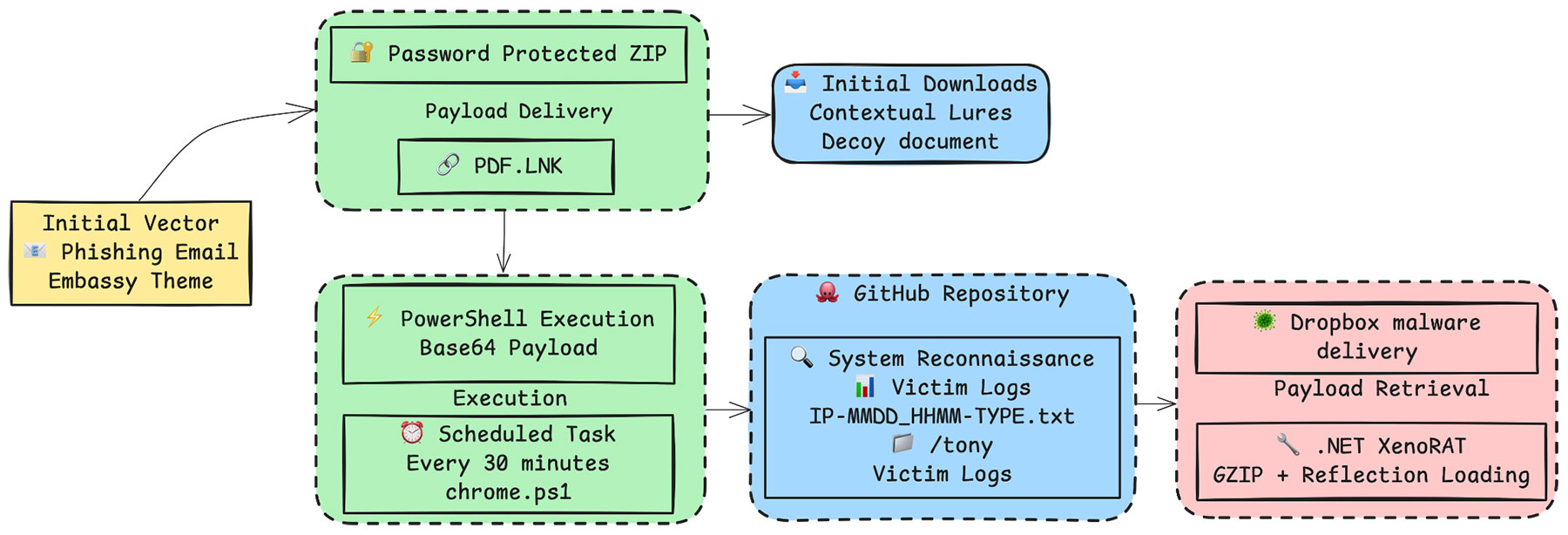

The attackers conducted a multi-stage intrusion campaign, orchestrated as follows (see Figure 1):

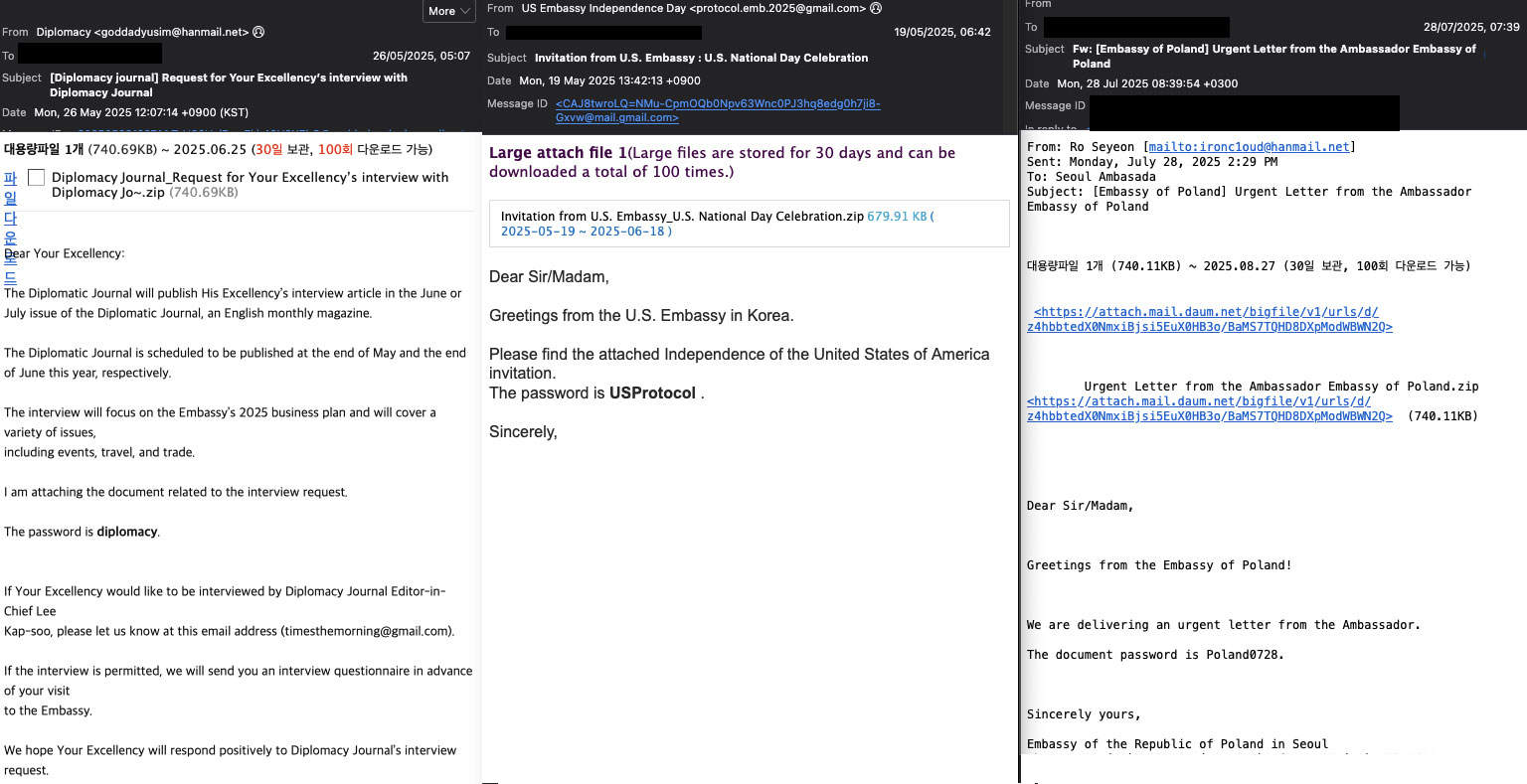

- Initial vector – spear-phishing: The campaign’s entry point was a wave of spear-phishing emails sent to personnel at embassies and foreign ministries in Seoul. These emails were carefully crafted to appear legitimate, often spoofing real diplomats or officials. For instance, one lure email impersonated a First Secretary of an EU delegation, offering “EU political counselors meeting minutes” as an attachment. Another, sent on May 19, 2025, posed as a protocol officer from the U.S. Embassy, inviting recipients to an Independence Day event. Common across all emails was the inclusion of a ZIP file (indicated by documents like “Attachment: Invitation...zip; Password: USProtocol”). Inside each ZIP was a Windows shortcut with double extension (pdf.lnk) file disguised with a PDF icon and name (e.g., "Urgent Letter from the Ambassador.pdf.lnk").

- Payload delivery – password-protected archives: To deliver malware while evading detection, the phishing emails are linked to password-protected ZIP archives holding malicious files. These archives were delivered through cloud storage links (e.g., Dropbox or Google Drive URLs) or Korean email services like Daum. The use of encrypted ZIP attachments helped the attackers evade antivirus scanning and also added legitimacy, i.e., the email provided the password as if for confidentiality.

- Social engineering – contextual lures: The spear-phishing content was carefully crafted to mimic legitimate diplomatic correspondence. Many emails included official signature, diplomatic terminology, and references to real events (e.g., summits, forums, or meetings). The attackers impersonated trusted entities (embassies, ministries, international organizations), a long-running Kimsuky tactic. By strategically timing lures alongside real diplomatic happenings, they enhanced the credibility. For instance, a fake conference invitation in mid-2024 coincided with actual Korea–Africa cooperation forums [2], and a phony “Iran Invest Show” expo invitation written in Persian, Arabic, English, and French paralleled real investment expos scheduled [3]. Such precise timing and context significantly increased the likelihood that targets would open malicious attachments.

- Execution – malicious .LNK and PowerShell: Once a victim extracted and opened the supposed document, a malicious LNK shortcut executed an embedded PowerShell command. The .LNK file, camouflaged with a Hangul document icon and filename, acted as the dropper. Opening it triggered an obfuscated PowerShell script that decoded a base64-encoded payload and executed it in memory. The PowerShell script would reach out to attacker-controlled GitHub repositories (e.g., downloading payload files from raw.githubusercontent[.]com) and establish persistence through scheduled tasks for continued execution.

- Reconnaissance – host enumeration: The malicious script performed reconnaissance on the victim system. It gathered system information including OS details (Version, BuildNumber, OSArchitecture, etc.), last boot time, computer system information, system type (laptop vs desktop), OS install date, running processes, and IP address. This data gives the attackers context about the target environment.

- Exfiltration – GitHub API uploads: For exfiltration, the malware did not communicate with traditional C2 servers at this stage. Instead, it abused the GitHub API to upload data. Using the attacker’s hardcoded credentials (a personal access token), the malware would push files into the "tony/" directory of the attackers' GitHub repository. The stolen data is formatted with timestamps and IP addresses in filenames like "[IP]-[MMDD_HHMM]-XXX-kkk.txt" and "[IP]-[MMDD_HHMM]-0956_info.txt", then base64-encoded and uploaded via PUT requests to the GitHub Contents API. This method allowed data to be exfiltrated over HTTPS with GitHub's domain – blending in with legitimate traffic. The malware automatically deletes local reconnaissance files after successful upload.

- Command-and-Control – GitHub as C2 hub: In addition to exfiltrating data, the malware could retrieve instructions from the private repo. For example, the attackers maintained a text file (onf.txt) in the repo that served as a “reconnaissance” indicator : the malware would check this file’s content to obtain the URL of the latest RAT payload (which was hosted on Dropbox as a GZIP’d file). By simply updating onf.txt in the repository (pointing to a new Dropbox file), the operators could rotate payloads to infected machines. They also practiced “rapid” infrastructure rotation: log data suggests that the ofx.txt payload was updated multiple times in an hour to deploy malware and to remove traces after use. This rapid update cycle, combined with the use of cloud infrastructure, helped the malicious activities fly under the radar.

- Payload retrieval and RAT deployment: The PowerShell downloader fetched an obfuscated payload from Dropbox, stored with a benign extension (.rtf) to evade detection. The malware required a "GZIP header fix" routine where the script systematically overwrote the first 7 bytes with the proper GZIP magic sequence (0x1F8B08...) before decompression. This GZIP header manipulation technique has been consistently observed across multiple North Korean campaigns, including recent operations documented by AhnLab ASEC [4] and Securonix researchers [5].

After header reconstruction, the script decompressed the payload using System.IO.Compression.GzipStream and loaded the resulting .NET assembly directly into memory via reflection ([System.Reflection.Assembly]::Load()). The final payload was a variant of XenoRAT obfuscated using Confuser Core 1.6.0, consistent with the "MoonPeak" malware family attributed to North Korean actors [6]. Our analysis identified the characteristic GUID "12DE1212-167D-45BA-1284-780DA98CF901", unique mutex “Dansweit_Hk65-PSAccerdle”, matching known Kimsuky patterns. This execution technique ensured the actual RAT never touched disk in executable form, providing complete system control through keystroke logging, screenshot capture, webcam/microphone access, file transfer, and remote shell capabilities. The RAT's stealth features enabled persistent espionage access to diplomatic communications and credentials.

Email phishing lures and activity timeline

The phishing campaign unfolded in several waves, each with distinct themes tailored to diplomatic targets. Trellix Email Security detected 19 spear-phishing emails were sent to at least four groups of embassies/ministries (Western, Central, Eastern, and Southern European diplomatic missions in Seoul), indicating a broad but coordinated espionage effort. The timeline below highlights key phases and lure themes, demonstrating how the attackers adjusted their social engineering content over time:

- Phase 1: Initial probing (early March 2025): The campaign’s earliest known email was sent on March 6, 2025 to a Central European embassy. It was masked as a routine notice titled “Gas Facility Safety Inspection Service”. The sender, purportedly an official named Kim Taesung from a hanmail.net address, attached a ZIP file (Gas Facility Safety Diagnosis Service.zip, password “gas2025”).

Although relatively mundane in theme, this email was likely a test of malware delivery to see if the method would work. A week later, on March 18, 2025, the attackers pivoted to a military theme, targeting multiple Western European embassies with invitations to a “UNC (United Nations Command) military event luncheon”. Here they impersonated a Korean defense protocol via another Hanmail email address and used a similarly formatted ZIP (250319_UNC AMB Luncheon..zip, password “2025UNC”).

By late March (24th–26th), a third lure variant appeared: “EU Political Counselor Meeting Minutes,” sent to EU delegation staff by spoofing a legitimate EU diplomat. This phase established the pattern of impersonation—each email feigned to be from a credible source known to the recipients (often borrowing real names/titles) and delivered content relevant to ongoing diplomatic activities.

- Phase 2: Peak diplomatic targeting (May 2025): the campaign resurged in May with more complex lures and a wider net of targets. On May 13, 2025, an email to a Western European embassy pretended to be from a high-ranking EU delegation official about a “Political Advisory Meeting at the EU Delegation on May 14.” The ZIP attachment (hosted on Dropbox) was named accordingly and protected with the password “0514EU.”

Shortly after, around May 19, multiple embassies in Seoul received emails from “U.S. Embassy Protocol” (using a spoofed Gmail address, protocol.emb.2025@gmail.com) inviting them to a “U.S. Independence Day Celebration” event. This lure stood out by volume—it was sent to many recipients—and by using an American holiday theme to target non-U.S. embassies, likely intending to compromise officials who would RSVP. The attachment was again a Dropbox link (Invitation from U.S. Embassy_U.S. National Day Celebration.zip, password “USProtocol”).

By May 26, 2025, the attackers launched another wave: emails titled “Request for Your Excellency’s interview – Diplomacy Journal” went out to numerous embassies (Western, Central, Southern Europe). The sender posed as Lee Kap-soo, managing editor of a (fictitious) Korean diplomatic journal, soliciting interviews. This date (late May) represented the peak of activity, with multiple distinct themes deployed in parallel.

- Phase 3: Military and bilateral lures (June–July 2025): In June, the campaign incorporated themes related to the U.S.–Korea military alliance. On June 10, 2025, an email ostensibly from “Chang Hyo Chong Eric” (a variant of the earlier UNC protocol officer identity) was sent to a Southern European Foreign Ministry. It contained an updated “UNC/USFK Ambassadors Integration Event” invitation (ZIP password “UNC0625”). The date in the password (0625) likely references June 25, aligning with the event title.

Finally, in late July, the attackers returned to a bilateral diplomatic angle: on July 28, 2025, an email from one “Ro Seyeon” claimed to carry an “Urgent letter from the Ambassador of Poland”. This was sent to at least one Eastern European embassy. The archive (Urgent Letter from the Ambassador Embassy of Poland.zip, password “Poland0728”) again contained a malicious LNK. This late-July incident is notable as it occurred after a gap in June/early July activity, possibly marking a resurgence after a break (of which is explored in the Attribution section).

Throughout these phases, the phishing lures exhibited consistency in tactics. The file delivery was predominantly via Daum’s “attach.mail.daum.net” file service. And they often expired shortly after use as a built-in feature of the service. The archive file names closely matched the email subject and were crafted to seem official and urgent (see IoCs section for a list).

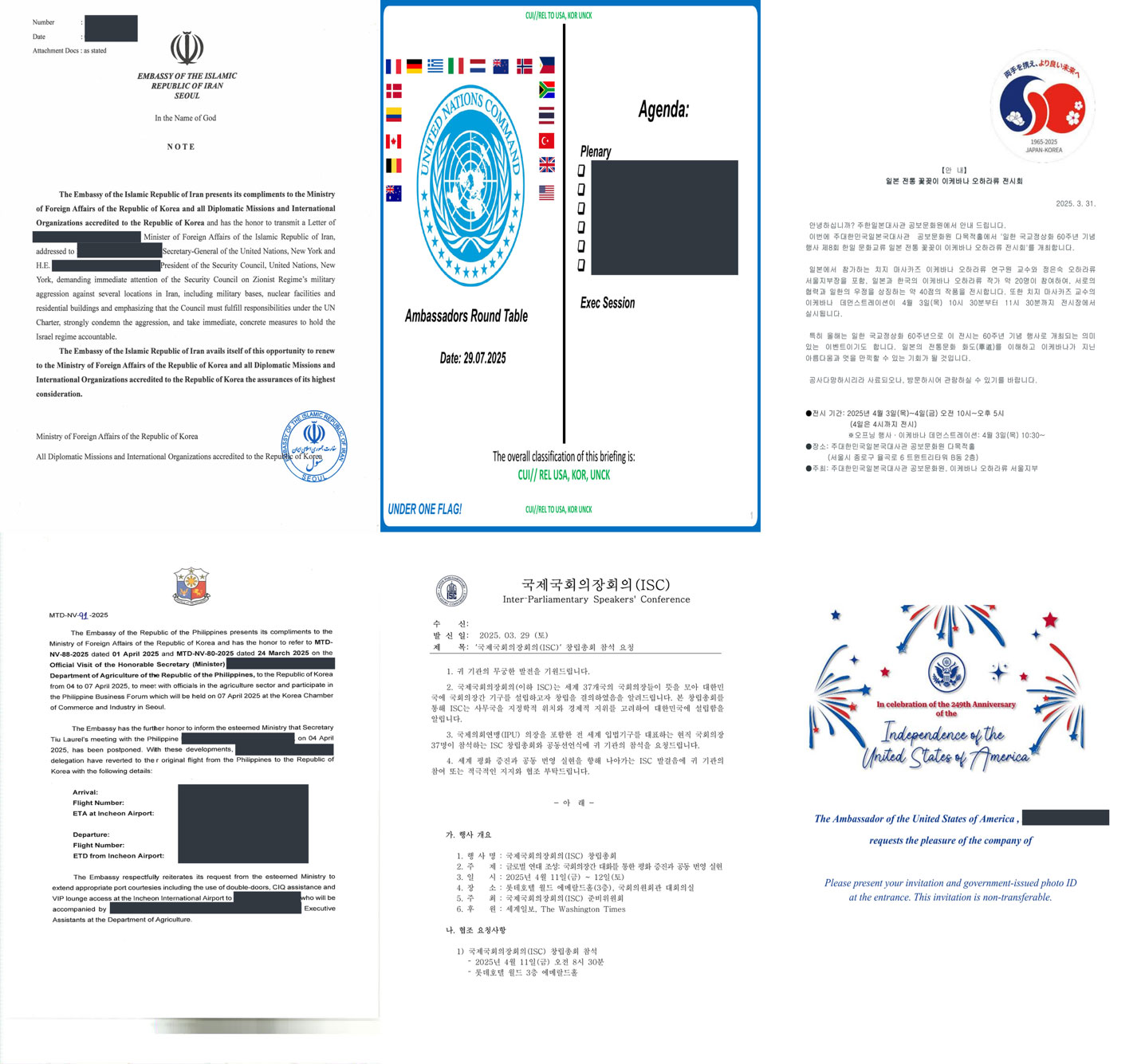

Social engineering and decoy Documents

The social engineering side of this campaign produced a stash of decoy documents as phishing lures. Attackers crafted and deployed at least 54 unique PDF lure documents spanning more than a dozen different themes and languages, including Korean, English, Persian (Farsi), Arabic, French, and Russian (Cyrillic). This deliberate linguistic and thematic diversity underscores the attackers' sophisticated understanding of their targets' contexts and professional environments. Over 40% of the decoys took the form of official letters, diplomatic notes, or formal announcements.

As shown in Figure 3, the attackers demonstrated a remarkable degree of localization and topical relevance in their decoys:

- Diplomatic invitations and conferences: Many decoys took the form of invitation letters to high-profile events. One example is a faux invitation to the “Founding Assembly of the Inter-Parliamentary Speakers’ Conference (ISC)” in Seoul. The decoy (two PDF versions in English and Korean were created in the “world” campaign of operator landjhon on the same date) claims to invite parliamentary speakers from 37 countries to a conference in South Korea. Notably, the domain used (isc-parliment.org) is a lookalike with a spelling error. No public record exists of an actual ISC event matching the described details, suggesting this was entirely fabricated.

Another decoy entitled “26th World Korea Forum” was bilingually written (English and Korean) and purported to be an invitation to a Korea-Africa forum in Nairobi in August 2024. It overlapped with real-world diplomatic outreach (2024 saw increased Korea–Africa cooperation forums) [2], lending realism. By piggybacking on timely international events, the threat actors made their lures more convincing.

- Official embassy correspondence: Several decoys impersonated embassy cables and diplomatic letters. For instance, one PDF was formatted as a note verbale from the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Seoul, addressed to the South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the UN. This decoy employed accurate diplomatic formatting, language, reference numbers, and even official emblems, significantly heightening the authenticity perceived by the target.

- Media and academic themes: In some cases, the lure was an ostensibly benign document that would appeal to diplomatic staff or subject matter experts. One decoy, for example, was an “Interview Questionnaire” from Diplomacy Journal (a fictitious publication) targeting an embassy’s press officer. Another was a fake research paper or policy brief on North Korea–Russia relations and U.S. foreign policy, formatted like a think-tank report (complete with the logo of a known publication The Diplomat and a real article reference URL [7]).

By using open-source content (or slight modifications thereof), the attackers gave the decoy credibility—if a victim skimmed it, they would see familiar content relevant to their work. These types of decoys suggest the campaign aimed not only to infect targets but also to gather intelligence: a victim might willingly fill out the interview form or reply with information.

- Administrative and other lures: A few decoys had very specialized themes, indicating particular targeting. For instance, one lure was a school admission form for an international school in Seoul (written in English and Korean)—possibly used if the target had family or ties to that institution. Another decoy was a hospital health check-up form (impersonating the Soon Chun Hyang University Hospital in Seoul), likely aimed at expats who might seek medical services.

Crucially, none of these decoy documents carried malicious code themselves. The real harm was done by the hidden scripts and RAT; the PDFs were a smokescreen. The operation expended effort to appear authentic to diverse targets (Korean officials saw Korean-language content; Middle Eastern diplomats saw content referencing their region in native scripts, etc.).

Through detailed cross-referencing with real-world events, Trellix observed that phishing attacks frequently aligned with actual diplomatic or regional events. For example, the Iranian Kish Island expo decoy corresponded to a real investment exhibition series (Kish INVEX) that indeed takes place annually.

Additionally, the EU meeting lure on March 26 was one day after the supposed meeting date in the filename (250325), likely attempting to look like follow-up minutes. The UNC military event lures in March came just before a known annual military exercise timeframe, lending contextual plausibility. Additionally, several emails were sent during early morning hours (Korean time), e.g., between 6 and 9 AM, so that they would be waiting in the target’s inbox at the start of business—a common tactic to increase the chance of users opening them.

Interestingly, our analysis discovered that some PDF decoy content was re-used across multiple campaigns of the two Github operators. We identified at least eight sets of duplicate or near-duplicate PDFs used in different phishing waves. For example, the exact text of a “Diplomatic reception invitation” appeared in lures attributed to two different sender operators a month apart.

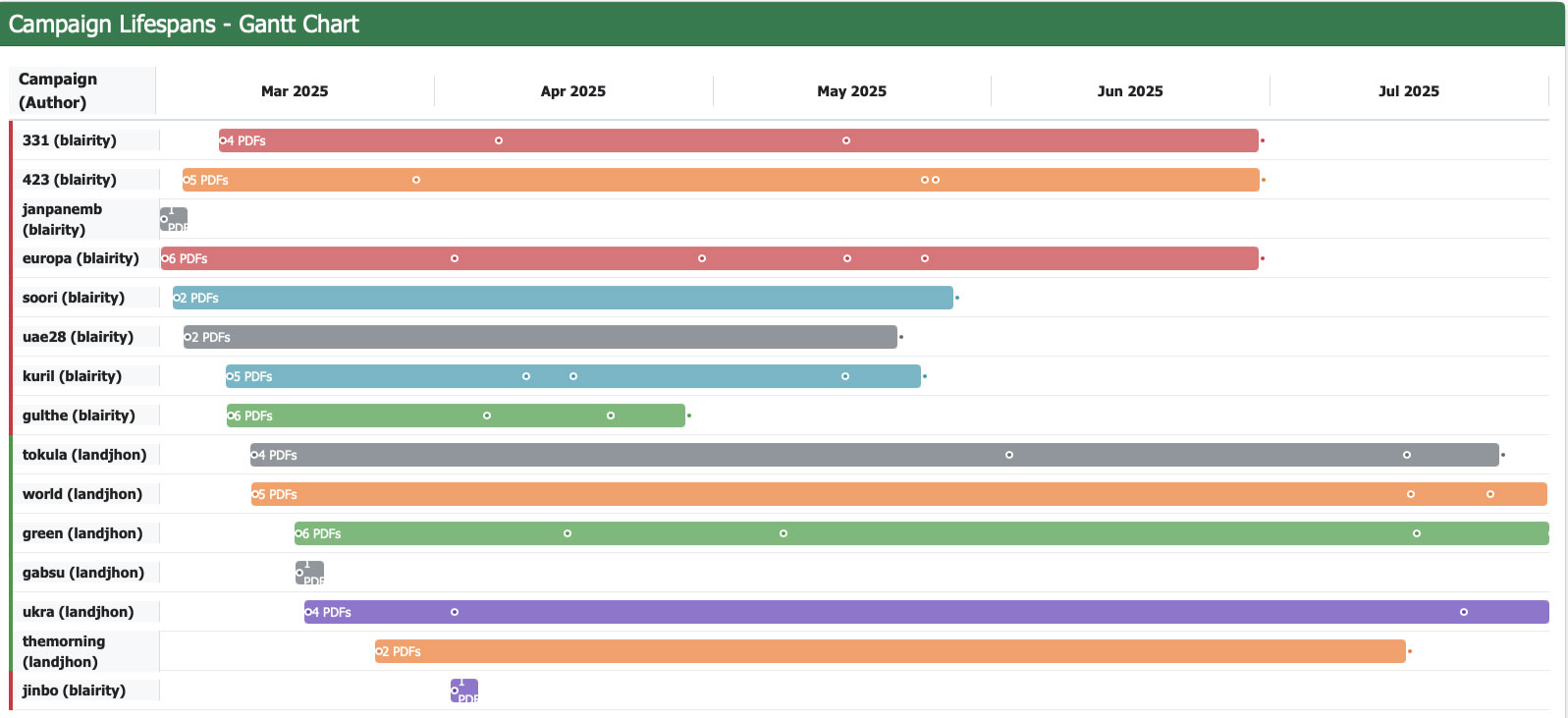

Campaign infrastructure

Our investigation into the campaign’s infrastructure reveals a coordinated use of legitimate platforms and custom domains, pointing strongly to DPRK-linked operators. The adversaries created at least two GitHub accounts for this operation: “blairity” and “landjhon.” Within these accounts, they operated a cluster of private repositories with innocuous names:

- blairity’s repos: 331, 423, europa, gulthe, janpanemb, jinbo, kuril, soori, uae28

- landjhon’s repos: gabsu, green, themorning, tokula, ukra, world

The repository names often correspond to themes or keywords from the decoys—for example, “uae28” held content related to the UAE delegation letter, and “themorning” related to the “Morning Times” diplomacy persona, etc. Each repository functioned as a silo for a specific phishing theme or target set, containing the decoy documents, the PowerShell scripts, the gathered logs, etc. The use of GitHub as C2 has been reported before in Kimsuky context. A June 2025 report by Enki WhiteHat detailed how Kimsuky actors abused GitHub (accounts “Dasi274” and “luckmask”) in a similar fashion [8]. While Trellix observes that this technique to be part of the actor’s broader playbook, our analysis here focuses exclusively on the embassy-targeted espionage activity.

Pivoting on the indicators, we identified an important piece of attacker infrastructure: an IP address used as an email sender and for testing. The IP 158.247.230[.]196 (Vultr VPS in Seoul) was found in both the emails and in log files. This IP has been confirmed as Kimsuky APT infrastructure associated with a XenoRAT campaign. Trusted sources linked another IP (141.164.49[.]250) in this cluster to APT43. We also tracked bp.nidnaver[.]cloud tied to this campaign. This domain resembles a mix of Naver’s phishing domain. While we did not see active use of this domain in the phishing chain, it may have served as a secondary malware host.

Log data from the repositories indicate the attacker’s operational environment. The attackers operated from virtualized Windows 11 Pro and Server 2022 environments. These VMs, emulated under BOCHS, shared consistent specs (4 GB RAM, 64-bit), with generically labeled hostnames (e.g., DESKTOP-OEFCI0, DESKTOP-USY2245) and user profiles like tienqang65@gmail.com, possibly reflecting either alias accounts or Microsoft-linked VMs.

The attacker machines exhibited signs of developer-level usage: Chrome instances in excess of 20 processes, frequent PowerShell usage, Notepad++ for script editing, Bandizip (a Korean zip tool) for archive handling, and even active Windows Defender processes. Remote management tools (e.g., rdpclip.exe) and cloud services like Azure Arc and OneDrive were also detected, indicating possible use of legitimate cloud-native tooling.

Resource monitoring highlighted that the XenoRAT server process consumed 3.4 GB of memory and had hundreds of handles open. This was on the Server 2022 machine, hinting it was handling multiple connections or large data throughput.

All these details portray an adversary operating with a professional setup: dedicated VMs for C2, consistent workflows, and the use of cloud-hosted servers in the target’s region for C2 reducing latency and not raising geolocation red flags. The use of Korean services and infrastructure was likely intentional to blend into the South Korean network. It’s a known Kimsuky trait to operate out of Chinese and Russian IP space while targeting South Korea, often using Korean services to mask their traffic as legitimate.

Threat intelligence attribution

On one hand, many indicators point to the well-known North Korean threat group Kimsuky (APT43). On the other hand, deeper analysis of the attackers’ behavior—especially their working schedule and pauses aligning with holidays—suggests Chinese nexus or support.

The technical evidence firmly aligns with historical Kimsuky operations. First, the choice of targets (diplomatic and political entities related to Korea) is squarely in line with Kimsuky’s profile as a DPRK-linked espionage unit focused on foreign policy intelligence. The use of Korean cultural lures and Korean email services (Hanmail) also echoes past campaigns attributed to Kimsuky.

Crucially, specific IoCs from this operation directly overlap with known Kimsuky infrastructure. The operation fits North Korea’s Kimsuky playbook: state-sponsored espionage targeting diplomats, using tailored phishing and custom tools. One phishing email impersonated a media correspondent (“The Morning Times”) using sender address timesthemorning@gmail.com, inviting an interview with an ambassador—an alias observed repeatedly in DPRK-linked phishing attempts targeting U.S. persons from February–September 2024 per a trusted source.

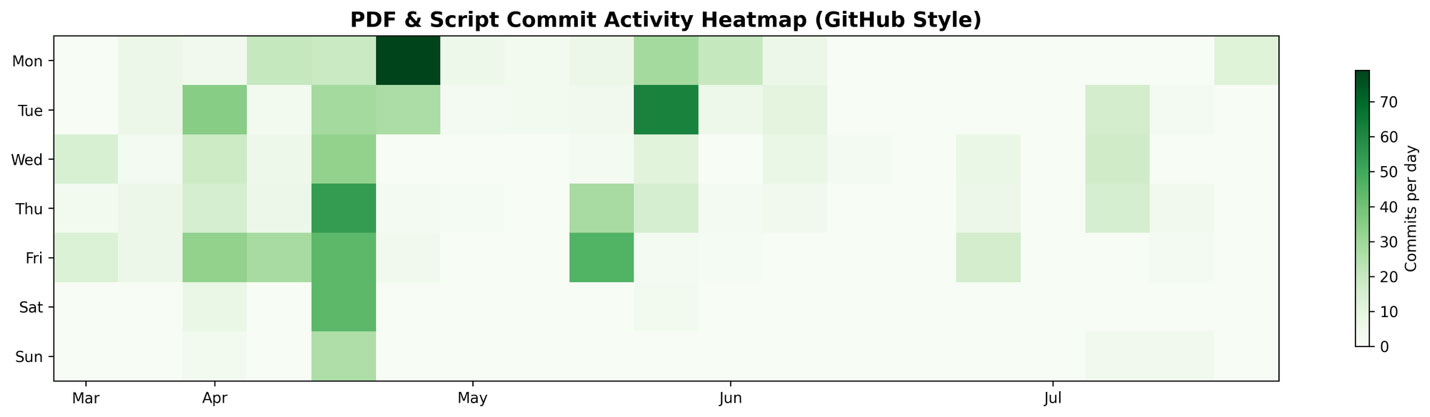

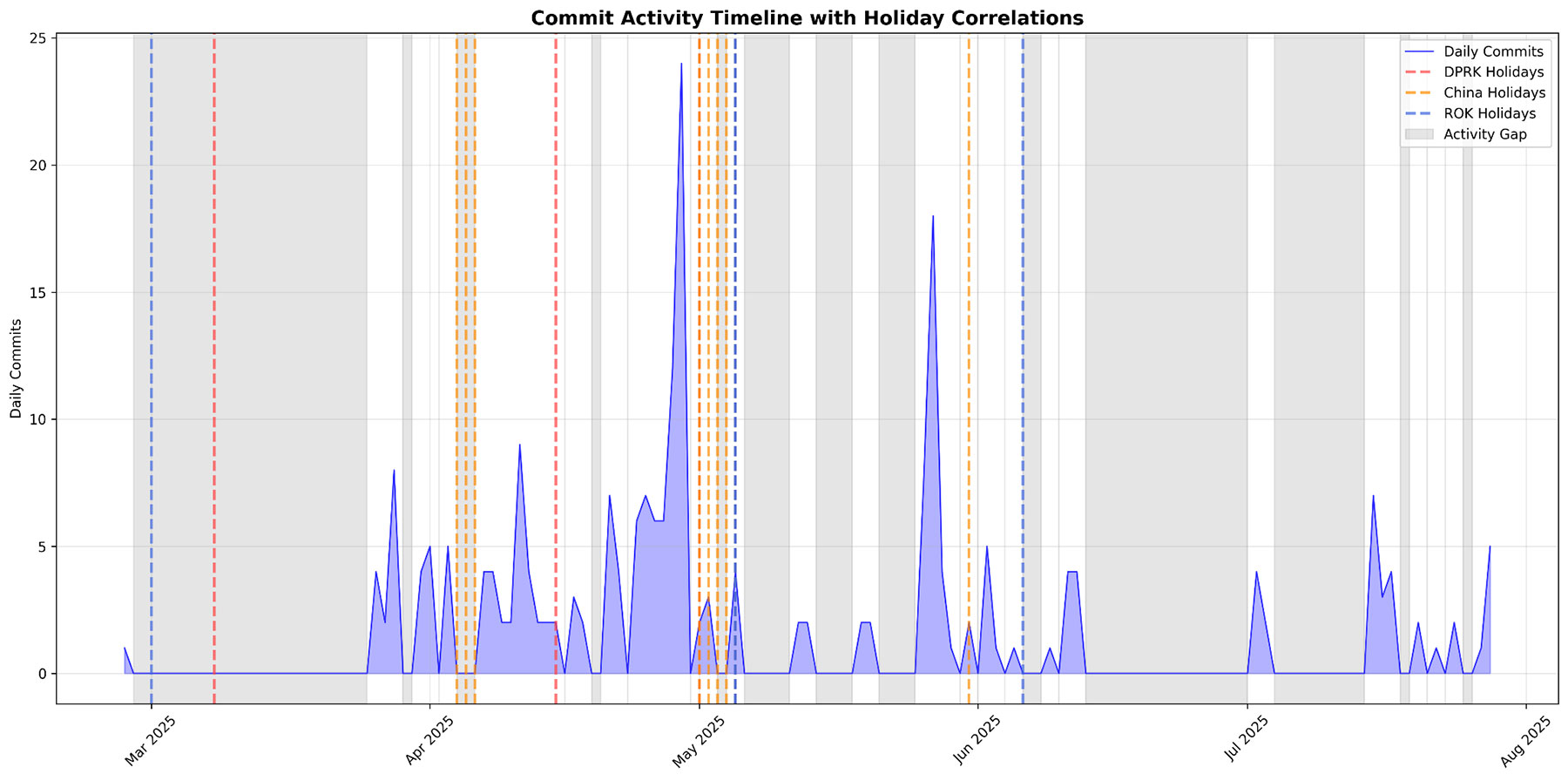

However, an intriguing puzzle emerges when looking at operational rhythms. We performed a time-based analysis of the attackers’ activity and correlated it with international holidays and weekends. Our timezone analysis of activity revealed that the vast majority of attacker operations originated from the +08:00 timezone (62%), consistent with China, while a smaller share aligned with +09:00 (35.5%), typical of the Koreas.

Furthermore, the threat actor showed consistent Monday–Friday, 8AM–6PM working hours in the Asia timezone, indicating this is a professional job, not irregular night hacker hours. We noticed that during major Chinese national holidays, the attackers had complete activity gaps, whereas North Korean and South Korean holidays did not produce such clear stops. For instance, during the Qingming Festival (April 4–6, 2025)—an important holiday in China— there was a perfect 3-day pause in commits and phishing activity.

Similarly, the Labor Day Golden Week (May 1–5, 2025) saw a multi-day halt in operations. In contrast, South Korean holidays (e.g., Korean Memorial Day in June) and North Korean holidays did not align as strongly—the coverage for DPRK holidays was only ~33% (low confidence).

The observed Chinese work patterns and holiday correlations raise attribution questions, as they could indicate either North Korean operatives working from Chinese territory, a Chinese APT operation mimicking Kimsuky techniques, or a collaborative effort leveraging Chinese resources for DPRK intelligence objectives. This phenomenon is well-documented in public reporting; for example, U.S. Department of Justice indictments and Center for Strategic & International Studies have both confirmed that North Korean cyber operators are frequently stationed in China and Russia, leveraging local infrastructure to facilitate their campaigns (see [9], [10]). The campaign is attributed to Kimsuky (APT43) with DPRK as the sponsor, but we have medium-confidence that the operators are operating from China or are culturally Chinese.

In conclusion, this campaign can be viewed as a North Korean espionage campaign in motive, targeting, and toolkit, but one that interestingly mirrors Chinese operational cadence. The key takeaway is not just whodunit, but how it was done: through innovative abuse of common platforms, careful social engineering, and cross-border execution. By unmasking this campaign, Trellix aims to help potential targets fortify their defenses and to chip away DPRK-linked operators in future espionage attempts.

MITRE ATT&CK technique mapping

| Tactic (MITRE Category) | Technique | ID |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | Spear Phishing Attachment | T1566.001 |

| Spear Phishing Link | T1566.002 | |

| Execution | User Execution: Malicious File | T1204.002 |

| Scripting: PowerShell | T1059.001 | |

| Persistence | Scheduled Task/Job | T1053.005 |

| Defense Evasion | Obfuscated Files or Information | T1027 |

| Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name/Type | T1036.005 | |

| Discovery | System Information Discovery | T1082 |

| Exfiltration | Exfiltration Over Web Service (Cloud) | T1567.002 |

Trellix detection

| Product |

Signature |

| Trellix Endpoint Security (ENS) | LNK/Downloader.ZRD XenoRAT/Packed.A |

| Trellix Endpoint Security (HX) | XENORAT (FAMILY) |

| Trellix Network Security Trellix VX Trellix Cloud MVX Trellix File Protect Trellix Malware Analysis Trellix SmartVision Trellix Email Security Trellix Detection As A Service Trellix NX |

FEC_Trojan_LNK_Generic_14 Trojan-JACI!0DE7202F1F54 FE_Backdoor_MSIL_Generic_29_FEBeta FE_Backdoor_MSIL_XENORAT_2_FEBeta FE_Backdoor_MSIL_XENORAT_3_FEBeta Suspicious Apicall Possible .NET RAT Activity Suspicious Process Launch Suspicious File Job with Powershell as Target Suspicious File Execution observed Suspicious File Dropped by .lnk File |

| Trellix EDR | PowerShell creates and executes suspicious script file (suspicious file path) - T1105, T1059.001 Potential attempt to execute script hosted at raw.githubusercontent.com via PowerShell - T1059.001, T1105, T1134 Suspicious DNS Query (Commonly Abused Web Services) by Script Interpreter - T1059.005, T1071.004, T1568 Unexpected attempt to resolve DNS lookup for 3rd party web services domain (potential C2) - T1102.002, T1105, T1102.003 Created a new scheduled task via PowerShell command - T1059.001, T1053.005 Downloaded a file using PowerShell Invoke-WebRequest command - T1059.001, T1105, T1071.001 Executed PowerShell with very long command line - T1059.001 Discovered user information using PowerShell environment variables - T1033, T1059.001, T1087.001, T1083 Started service execution of a binary with no reputation - T1569, T1569.002 Changed Task Scheduler tasks - T1112, T1053.005 Suspicious process finding mscoreei.dll (Potential CLR hosting case) - T1106 |

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

File hashes

Name: Diplomacy Journal_Request for Your Excellency’s interview with Diplomacy Jo~.zip

MD5: 5f704db7552a0b6b535b9c7c5f240664

SHA256: 1e10203174fb1fcfb47bb00cac2fe6ffe660660839b7a2f53d8c0892845b0029

Name: Invitation from U.S. Embassy_U.S. National Day Celebration.zip

MD5: 8b605de9d28c8c6477a996d4e5873e4e

SHA256: cf2cba1859b2df4e927b8d52c630ce7ab6700babf9c7b4030f8243981b1a04fa

Name: 250819_INVITATION UNCUSFK Ambassadors Integration Event.zip

MD5: 5b5d21904d4874da9a31d456c5bcef8f

SHA256: 4bfd068156adbcaa9c9701abbd72d21c0174f7ce6d3563962891e0538f6a36a7

Name: Update Schedule_INVITATION - 250625 UNC Ambassador_s Roundtable.zip

MD5: 488570af25f908e907c9732aae632b0f

SHA256: 9c5964753f8092a98f414a97cfb02cbe2692a02bea0d1b601ff205282fbf8a62

Name: Update Schedule_INVITATION - 250625 UNC Ambassador's Roundtable.pdf.lnk

MD5: bca4cac80c436e813d93eba1b25257d0

SHA256: 9f5460850a3b5b53568cd450e83406927776833778a8eb24955bcebdf9849321

Name: 250319_UNC AMB Luncheon and ART Attendee Submissions.pdf.lnk

MD5: 02430604d146e8e33554061344ca806e

SHA256: 48fe8b7c8ceb1575dcdb6cf9f717d322e3450b2a06d6fab3d05ca907048aa1cd

Name: 250319_UNC AMB Luncheon and ART Attendee Submissions.zip

MD5: 25595588106848b2054497ceba1a2d66

SHA256: c72f52813110685fe16af777f4ea5da2521270b4a906aae2fac98b746e3021ca

Name: Diplomacy Journal_Request for Your Excellency’s interview with Diplomacy Journal.pdf.lnk

MD5: ff37eb655a96b71e7dc08b4d91e1daea

SHA256: f372b16ec015767320a8334b73405943b0222ea125241907235fd4f347832d0e

Name: Invitation from U.S. Embassy_U.S. National Day Celebration.pdf.lnk

MD5: 0e0f720193204cbd1a2c847d76f9e82f

SHA256: 892734d408626a9bb557346c5f80343d5f415e8e536f2aad30df74086865fe50

Name: 250819_INVITATION UNCUSFK Ambassadors Integration Event.pdf.lnk

MD5: 45bd30d3a52904a7fe64fd97c31e3a1c

SHA256: f462439a4590e9ee053573639a82e36304897f0a695729990c108bce6518f556

Name: Political Advisory Meeting to be held at the EU Delegation on May 14.zip

MD5: 60895bbfd40b902513afda50b28e80da

SHA256: 6dea2bf9512f618e3316f58d4f830e2a5cd746b778b125a91403da02de691d89

Name: Urgent Letter from the Ambassador Embassy of Poland.pdf.lnk

MD5: dfacbcf7ef2a3080f9cd785329e7896b

SHA256: 4a3e9f6b214effe5028a0bf36776190916621fd7977bf3720cb6ead34d9ee20d

Name: Urgent Letter from the Ambassador Embassy of Poland.zip

MD5: 8a94fe218e7970839b83b53a824ebc47

SHA256: 7ac1cb59cf1d5167b4f545c5a49f1c3db71493b448bd81a9a7ad7e25dcd7b943

Name: krumhan.rtf (XenoRAT)

MD5: da19f3c42361ac84642e936e61c149a1

SHA256: 18ab9a5bd68314b8a91070f18ca9c2c9097a3441b058edccd304b0e33d6c1422

Name: bobokan.rtf (XenoRAT)

MD5: 752b8fc6f69c8153d6945ff608ae6b4e

SHA256: 90f53ae46c789884cfddc0d1d8f1ee7f8c4662b899fce51d5b01e94848554072

Network indicators

| Indicator | Type | Description |

| 141.164.40[.]239:443 | IP:port | XenoRAT C2 |

| 141.164.49[.]250:443 | IP:port | XenoRAT C2 |

| https://dl.dropbox[.]com/scl/fi/sb19vsslj13wdkndskwuou/eula.rtf?rlkey=axrb5o5mv14afu7g6e8s3d5s8&st=xy96nggc&dl=0 | URL | Final stage URL |

| https://dl.dropboxusercontent[.]com/scl/fi/c6ba7iwuke57d75j3mmte/eula.rtf?rlkey=t0jnirhxk48xdu8p74rqgv9dw&st=oofgjsq8&dl=0 | URL | Final stage URL |

| https://dl.dropbox[.]com/scl/fi/kpxdthefmdbxw9m31tao3/krumhan.rtf?rlkey=yhzti914uzn72wm4iruej24px&st=xjzyd4ip&dl=0 | URL | Final stage URL |

| https://dl.dropbox[.]com/scl/fi/4pydbg08752rsw6us7e5x/bobokan.rtf?rlkey=b49lxndnjvigz58o7ptwqrsbm&st=9rtwns0x&dl=0 | URL | Final stage URL |

| https://bp.nidnaver[.]cloud/info.php | URL | Final stage URL |

| https://bp.nidnaver[.]cloud/forbhmypresent.66ghz.com/dn.php | URL | Final stage URL |

| 158.247.230[.]196 | IP | Email sender, attacker IP, Vultr Cloud, South Korea |

| 141.164.41[.]17 | IP | Email sender, attacker IP, Vultr Cloud, South Korea |

| 165.154.52[.]140 | IP | Email sender, Korean infrastructure |

| 165.154.52[.]210 | IP | Email sender, Korean infrastructure |

| 141[.]164[.]49[.]250 | IP | Attacker IP |

| 158[.]247[.]249[.]243 | IP | Attacker IP |

Email IoCs

| Sender Name | Sender Email | Recipient | Date | Phishing Lure | Password |

| 김태성 (Kim Taesung) | 1gai2000@hanmail.net | Central Europe Embassy | 2025-03-06 | Gas facility safety inspection service | gas2025 |

| Chang, Hyo Chon | goddadyusim@hanmail.net | Western Europe Embassy, Southern Europe Embassy | 2025-03-18 | UNC military event attendee documents | 2025UNC |

| Chang, Hyo Cho | goddadyusim@hanmail.net | Western Europe Embassy | 2025-03-24 | UNC military event follow-up actions | 0324UNC |

| LIEGOIS Carole | 1gai2000@hanmail.net | Central Europe Embassy, Eastern Europe Foreign Ministry | 2025-03-26 | EU political counselors meeting minutes | europa |

| EKFELDT Fredrik | execuetive.director@gmail.com | Western Europe Embassy | 2025-05-13 | EU Delegation political advisory meeting | 0514EU |

| US Embassy Independence Day | protocol.emb.2025@gmail.com | Western Europe Embassy | 2025-05-19 (multiple) | US Independence Day celebration invitation | USProtocol |

| Diplomacy (Lee Kap-soo) | goddadyusim@hanmail.net | Western Europe Embassy, Central Europe Embassy, Southern Europe Embassy | 2025-05-26 (multiple) | Korean diplomatic journal interview request | diplomacy |

| Chang Hyo Chong Eric | landf5503@gmail.com | Southern Europe Foreign Ministry | 2025-06-10 | UNC Ambassador's Roundtable invitation | UNC0625 |

| Ro Seyeon | ironc1oud@hanmail.net | Eastern Europe Embassy | 2025-07-28 | Urgent letter from Polish Ambassador | Poland0728 |

| N/A | timesthemorning@gmail.com | Western Europe Embassy | 2025-04-24 | UNCMS Working Group - RoDs | N/A |

| Chang Hyo Chong Eric | landf5503@gmail.com | Western Europe Embassy | 2025-07-28 | USFK Ambassadors integration event | 2025UNC |

References

| [1] | NSA, U.S., ROK Agencies Alert: DPRK Cyber Actors Impersonating Targets to Collect Intelligence. "https://www.nsa.gov/Press-Room/Press-Releases-Statements/Press-Release-View/Article/3413621/us-rok-agencies-alert-dprk-cyber-actors-impersonating-targets-to-collect-intell/," [Online]. |

| [2] | UNESCO, [Online]. UNESCO Forum enhances Korea-Africa educational collaboration. Available: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-forum-enhances-korea-africa-educational-collaboration. |

| [3] | Iran MFA, [Online]. Global Trade and Investment Opportunities. Available: https://bangladesh.mfa.gov.ir/en/newsview/751861/Global-Trade-and-Investment-Opportunities. |

| [4] | ASEC Ahnlab, [Online]. APT Attacks Using Cloud Storage. Available: https://asec.ahnlab.com/en/74034/. |

| [5] | securonix, [Online]. ANALYZING DEEP#DRIVE: NORTH KOREAN THREAT ACTORS OBSERVED EXPLOITING TRUSTED PLATFORMS FOR TARGETED ATTACKS. Available: https://www.securonix.com/blog/analyzing-deepdrive-north-korean-threat-actors-observed-exploiting-trusted-platforms-for-targeted-attacks/. |

| [6] | talosintelligence, [Online]. MoonPeak malware from North Korean actors unveils new details on attacker infrastructure. Available: https://blog.talosintelligence.com/moonpeak-malware-infrastructure-north-korea/. |

| [7] | The Diplomat, [Online]. NATO’s New Mission: Keep America in, Russia Down, and China Out. Available: https://thediplomat.com/2024/07/natos-new-mission-keep-america-in-russia-down-and-china-out/. |

| [8] | Enki, [Online]. Dissecting Kimsuky’s Attacks on South Korea: In-Depth Analysis of GitHub-Based Malicious Infrastructure. Available: https://www.enki.co.kr/en/media-center/tech-blog/dissecting-kimsuky-s-attacks-on-south-korea-in-depth-analysis-of-github-based-malicious-infrastructure. |

| [9] | DOJ, [Online]. 3 North Korean Military Hackers Indicted in Wide-Ranging Scheme to Commit Cyber-attacks and Financial Crimes Across the Globe. Available: https://www.justice.gov/usao-cdca/pr/3-north-korean-military-hackers-indicted-wide-ranging-scheme-commit-cyber-attacks-and. |

| [10] | CSIS, [Online]. Hidden Enablers: Third Countries in North Korea’s Cyber Playbook. Available: https://www.csis.org/analysis/hidden-enablers-third-countries-north-koreas-cyber-playbook |

Discover the latest cybersecurity research from the Trellix Advanced Research Center: https://www.trellix.com/advanced-research-center/

RECENT NEWS

-

Feb 10, 2026

Trellix SecondSight actionable threat hunting strengthens cyber resilience

-

Dec 16, 2025

Trellix NDR Strengthens OT-IT Security Convergence

-

Dec 11, 2025

Trellix Finds 97% of CISOs Agree Hybrid Infrastructure Provides Greater Resilience

-

Oct 29, 2025

Trellix Announces No-Code Security Workflows for Faster Investigation and Response

-

Oct 28, 2025

Trellix AntiMalware Engine secures I-O Data network attached storage devices

RECENT STORIES

Latest from our newsroom

Get the latest

Stay up to date with the latest cybersecurity trends, best practices, security vulnerabilities, and so much more.

Zero spam. Unsubscribe at any time.